“Quot homines, tot sententiae” – Latin Proverb

Loosely translated, the above proverb says that there are as many opinions as there are people. In the adoption of this proverb into the legal fraternity, it is said “Quot judices, to legalis sententiae”, which translates to there being as many legal opinions as there are judges.

The proverb above is the point of departure for this opinion piece. This is but one of many opinions regarding the matter between Jacob Zuma and the Zondo Commission that the ConCourt ruled on; by no means am I claiming to be presenting dogmatic truths in how the law must be interpreted. The law being the being that it is, guarantees that any given matter will always have varying opinions, and sometimes the prevailing opinions on a matter are not necessarily the best way to interpret the law. A disclaimer I must make, is that this opinion is not to defend or chastise one or other party involved in the cases I am going to cite beyond the analysis of the application of law as I believe to be correct.

There have been two other instances where I have strongly disagreed with the Constitutional Court in recent times, and the ruling that came on the 29th of June became the third time in four years I found myself opposed to the legal logic applied by the ConCourt. The notable similarity with all is that in all three instances, Jacob Zuma was at the centre of the cases (The learned collegiates of the legal fraternity, whether they like him or not, must agree that Jacob Zuma is a gift that keeps on giving as far as testing the parameters of the constitution and its interpretation in practice. The legal fraternity is richer in knowledge with all that he has put it through.).

The first time I disagreed with the ConCourt was on 22 June 2017, when the court unanimously ruled that the speaker of parliament had the constitutional powers to prescribe that the vote in the motion of no confidence against the president be by secret ballot (Case CCT 89/17). The ruling defeated the purpose of why we have representative democracy to begin with, because it said members of parliament could act without transparency and accountability to the people who voted. It baffled me how 11 constitutional experts could not see that simple fact. I filed an application for the ConCourt to rescind the judgement, with rule 29 of the Constitutional Court which accommodates certain rules of the uniform rules of court; with Rule 42 of the uniform rules of court, which speaks to rescissions, being one of these accommodated rules. The court dismissed it on the basis that the application had no prospects of success (Case CCT 202/17). That is to say, the court believed it had reached the right decision, with no errors, and was therefore not going to be convinced otherwise.

I dealt with the logic of why it is undemocratic for MPs to vote in secret here: Facebook: Yamkela F Spengane

https://www.businesslive.co.za/.../2017-04-19-steven.../

https://theconversation.com/south-africa-will-be-better...

One day, when the bench has changed significantly, we will take the matter back to the ConCourt, hoping that the court will at least grant it access to be heard. This is because while this ruling was meant for Zuma, it has wide reaching repercussions that impugn on democracy itself as a concept and ideal defended by the constitution. These repercussions will unfortunately persist long after Jacob Zuma is gone.

The second disagreement with the Apex court came in 2017 as well, December 2017 to be precise, when the court handed down judgement in Case CCT 76/17. The matter was heard by the full bench of the ConCourt, and the decision was split 7 to 4 in favour of the majority judgement authored by Justice Jafta. It also offered two dissenting judgments by DCJ Zondo and CJ Mogoeng respectively, as well as a concurring judgement by Justice Froneman. The two dissenting judgements cover my sentiments on the matter, summarised by Mogoeng’s opening paragraph at 223, which says of the majority judgement: “The second judgement is a textbook case of judicial overreach – a constitutionally impermissible intrusion by the Judiciary into the exclusive domain of Parliament”. As a result, I need not go further as to why I disagree with the majority judgement.

I still believe Parliament should not have been dictated to by the majority judgement, because in its own self-determined processes it had already motioned votes of no confidence – which are themselves a tool of holding a sitting president accountable – and this was an instance when it really felt that the Concourt Justices were playing politics in a very explicit way. The proposition of creating or amending one or other set of rules governing one or other ad hoc process of parliament must always come from parliament, through the set channels of parliament. However, because of this judgement, there is now precedence in our jurisprudence for a court of law to interfere with parliament, a provincial legislature or a city council, as to how it must go about doing its constitutionally mandated duties. This blurs separation of powers, the very tenet the constitution says is sacrosanct. It is another of the precedents that will persist long after Zuma is gone.

The third instance of me disagreeing with the ConCourt is the ruling which forms the heading of this piece (Case CCT 52/21), formally known as: Secretary of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State v Zuma and Others [2021] ZACC 18.

This is the talking point of the country at the moment, and is behind the reason the former president of the country reported to a correctional services centre in Estcourt, Kwa-Zulu Natal, to serve his sentence as sanctioned by the above judgement.

My differing with the ConCourt begins at the very beginning of the matter engaging with the ConCourt in December 2020. The ConCourt should not have granted direct access to the Zondo commission, and the matter should have gone through the court system like any civil matter. Alternatively, the Chairperson of the Commission should have laid criminal charges – as he had said – for Jacob Zuma being in contempt of the Commissions Act; but the process of going through the court system should have been the way for this matter. The Constitutional Court could have not granted access on the basis of exclusive jurisdiction, because it is established in law that the relief sort by the Zondo Commission on the matter could have been granted by lower courts; and the reasoning to grant direct access, as dealt with by Justice Jafta in paragraphs [53] to [72] in the unanimous judgement that orders Jacob Zuma to appear at the Commission (Case CCT 295/20) is one that is really sketchy in its consideration of applicable law. The Commission based its argument for direct access on urgency, in that the lifespan of the Commission was coming to an end on 31 March 2021 and therefore in the interests of the Commission fulfilling its mandate, it was important for the Court to use its discretion to accommodate a case that would under ordinary circumstances be dismissed. The urgency was not something the Commission could rely on as having had no control over however, and Justice Jafta notes correctly that it was the Commission’s own doing in failing to use its coercive powers on time with Jacob Zuma that it was now faced with this issue of its time lapsing before he appears. Based on this, the test on which to grant direct access was not met, and direct access should have been denied on those grounds. The ConCourt then throws the direct access application an exceptional lifeline, that it is in the public interest that Jacob Zuma appear before the Commission since he is central to the investigations of the Commission, and therefore on that basis direct access was granted. This was never going to be a legally justifiable reason, because while it was important for Jacob Zuma to appear before the Zondo Commission as a figure central to its investigations, it could never justify the Constitutional Court contorting itself to see him present himself to the Commission. There existed other avenues by which Jacob Zuma could be coerced in law to appear, without invoking procedurally questionable direction that has left some in the public with some doubt on the impartiality of the Constitutional Court. The need for the Constitutional Court to reflect itself in a light of impartiality was emphatically more important because it was being approached by one of its own Justices, and the second most senior of its Justices for that matter. Anything other than that always carried the risk of the question arising whether or not DCJ Zondo had used his influence as the Deputy Chief Justice to influence the decision to grant the Commission direct access under extraordinary circumstances. The question on its own, is a blemish the ConCourt could have done without. This was the beginning of a slippery slope, because no matter how the law would be applied from the time direct access was granted, including in the follow-up matter of contempt which culminated in the ruling that sanctioned Jacob Zuma to 15 months in prison, it would always go back to the original question of the impartiality or lack thereof of the direct access that was granted for the order in CCT 295/20 to be in effect.

The lamentation of Justice Theron in the minority judgement at how the granting of direct access to the Commission inadvertently limited the right of appeal for Jacob Zuma and that this limitation is unconstitutional ultimately (CCT 52/21 at [209] to [212]) is important to note in the argument I am advancing above. Justice Theron, and Jafta, who dissent to the sanction of the majority judgement in CCT 52/21, were in unanimity with the rest of the bench in granting direct access to the Zondo Commission in CCT 295/20, so perhaps it is in retrospect that they see the calamity of their initial ruling. I cannot emphasize enough, that once the direct access was granted, the jurisprudence was always going to be faced with ice-skating. The main/majority judgement had to hinge itself on the “unprecedented” nature in which Jacob Zuma attacked the judiciary, but that it is not precedence to apply shaky jurisprudence. It is for this reason Justice Theron asks at paragraph 262, and without an answer, that if you take away Zuma’s statements scandalising the court and “threatening the rule of law”, what does the main judgement have in law to sanction the punitive order it did? The answer is simple: nothing! It would be left with a simple civil contempt matter, and no legal basis to sanction a punitive order and has no basis in law.

It is unfortunate that it is only in retrospect that Justice Theron voices that the Commission placed the Constitutional Court in an “invidious position”, by approaching the Constitutional Court instead of going through with criminal proceedings (see CCT 52/21 at paragraph 265; nonetheless, it is appreciated that at least one Justice realises and will admit this. By so admitting, Justice Theron also admits that Direct Access should in fact have not been granted to the Commission in CCT 295/20; for then, the Constitutional Court would not be in the invidious position it finds itself in…

Justice or Power?

In her closing statement of CCT 52/21, at paragraph 141, Justice Khampepe says that her sanction to commit Jacob Zuma to imprisonment intends to send this unequivocal message: in this, our constitutional dispensation, the rule of law and the administration of justice prevails.

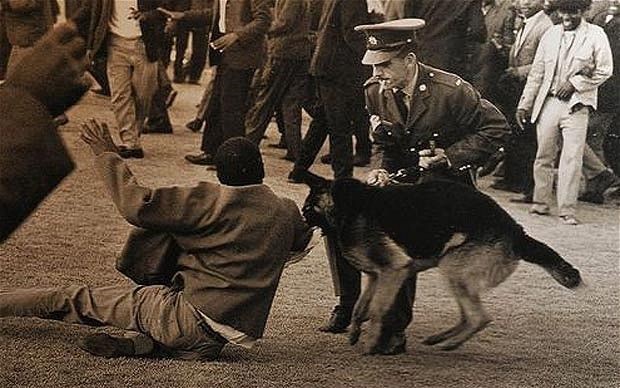

Both principles – that there is such a thing as rule of law in the most basic sense, and that law is a tool to mete out justice – are difficult to defend in actuality. Law by its very nature is subservient to power in the socio-political sense. We can study the birth of what we today call our common law from its origins in the various societies it descends from, and always find that law served the prevailing power of the day in society. Since the societies served by our common law have always been stratified, the prevailing idea of justice has always been that of those that find themselves at the top of this stratification of power – that is to say the ruling class. Without common convergence on what constitutes justice, it becomes difficult for law to be just. What we have then is law as a tool to ensure compliance with prevailing authority.

If we can frame law as a tool of chaperoning for authority as we have above, then we can ipso facto frame that law is unable to be the whip of the chaperoned and the chaperone at the same time. There is one who uses the law, and there is one who the law is used against. This dismisses the noble notion of the rule of law beyond our idealistic, utopian view of how society should function. We have in our time witnessed that the law does not interface the same way with everyone, and those entrusted as agents of the law are not immune to the biases of power.

What we have seen unfold before our eyes is what can be framed as “lawfare”, which denotes the use of law to achieve strategic political ends (a definition used in various premises by scholars studying the interfacing of law with society). South Africa has a long history with lawfare, in that even colonial conquest used the law extensively as a tool to subdue the natives and control them. The Apartheid State was a big experiment of lawfare, wherein nefarious laws were legitimised, passed and instituted against a people for the purpose of control and power. The so-called constitutional dispensation did not leave behind this ingrained inclination by those in power to use the law to advance certain political gains, hence we have seen the judiciary once more involved in political battles post-1994. It is not something that started recently, it has been a tool to use the courts for politics for the better part of 20 years. The beast is just growing the more it gets fed. Think of the judgement that was the premise of seeing a president recalled as an example of where we have been with judicial rulings as an influential factor of our politics. We have carried this and subsequent instances of bringing the courts to political matters that it is in fact a culture of our body politic to settle political scores through the courts. Perhaps, the continuous cross of territory between our law and our politics is that there is in fact no dichotomy that exists between the two, and when we come to our senses we can realise that we have struggled precisely because we wanted to separate the inseparable. The law is political, and it is not a mistake that it is being used for political gains by whoever finds themselves with power and ipso facto the “arsenal of the law”.

It is to say, then, that Justice Khampepe’s judgement was reinforcing where power lies, it was a reminder that those without the power on the day cannot challenge authority and get away with it. The law, by extension those with it as a tool in hand, can never have the day where people can think they are able to take their chances with it and get away. For if it was justice being served, then an alternative and rightful route to deal with the matter between the Zondo Commission and Jacob Zuma would have been taken, one that does not exceptionalise itself and deviate from law but seeks to follow the correct prescripts of jurisprudence. No matter how long it would have taken to go through the court system, and furthermore because the lifespan of the Commission was never cast in stone, extensions were always an option. Coercive means to see the witness in the form of Jacob Zuma appear and answer before the Commission was the key goal and should have stayed as such. Justice is a restorative phenomenon, not a punitive one. Power is the punitive phenomenon, in that it seeks to assert itself as an authority not to be transgressed impermissibly.

Thus, perhaps, the frame of that closing argument communicates that it is power whose authority will be instilled though the heavens may fall. To power, instilling that authority is justice…

The crisis still remains the precedent that this sets in law, as Justice Theron laments again in paragraph 263 of CCT 52/21, that when dealing with “unprecedented” issues, there is room by the courts to deviate from the constitution and all that it seeks to protect. By this judgement, as Justice Theron denotes, the threat is posed to litigants who are prosecuted in civil court by their adversaries, intent on seeing them punished, to have them sentenced punitively with no opportunity to purge their contempt and avoid punishment. Who then protects the constitution from the courts? More importantly for me, who protects the constitution from the constitutional court when it deviates from being the guardian of the very constitution as the court of last resort?

It brings about a very trying scenario, where supremacy must be established between the constitutional court and the constitution; because although the constitution is the sacrosanct between the two, the gateway is kept by the court who then ipso facto embody the constitution. This is, for the irony of it, the unprecedented nature of affairs we find ourselves in.

In closing, in perhaps a rather anticlimactic fashion:

Clarence Darrow, an American criminal defence lawyer of the 1920s and 30s, once pronounced that there is no such thing as justice, both in and out of the court. This is a sentiment I believe best describes our society when we agree to uncloak ourselves of the illusion of believing in proverbial justice that cannot be attained in reality. In the place of justice, we have the eternal contest of power, by opposing ideas of how human societies should be run, and these competing ideas have their own frames of justice and use the law as one of the available weapons to assert themselves. It is who is behind the prevailing ideas of society who are the arbiters of what “justice” is. Justice, is a function of power, and therefore not justice at all, more often than not.

I submit and pause here.