I’ve written, re-written, deleted, abandoned and re-written versions of this piece hundreds of times in the past three years or so.

It’s a mammoth task for the most gifted of wordsmiths; that means that it would be virtually impossible for me. How does one contextualise a force so great that it made its greatest contribution to a movement that ensured my ability to become a contributing member of society? How does one encapsulate the complexity of a personality so large that it has solely guided an entire movement and influenced history? How to include her work as a social worker, wife, mother, struggle icon, anti-apartheid activist, murder-accused and prisoner 1323/69?

How exactly does one write about Winnie Mandela?

After a while it became moot for me. Everything that could be written about Winnie Mandela has been done, from her inevitable link to the Mandela legacy documented in various texts, the biography Winnie Mandela: A Life by Anne Marie du Preez Bezdrob and Antjie Krog’s censure of her behaviour during the Truth and Reconciliation hearings to her own account of those all-important 491 days she was imprisoned. There is even a brief fictional account of her in the book The Cry of Winnie Mandela (Njabulo Ndebele), so to my mind, there was very little deviation – or justice – I could provide in any writing I would do about her.

So I stopped trying.

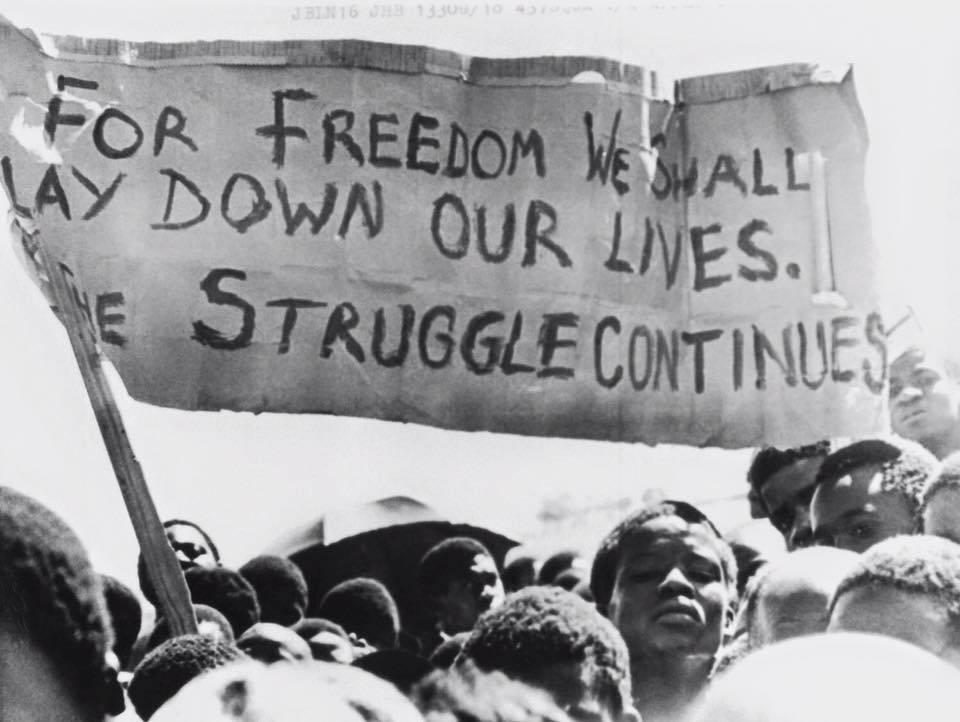

Until Bertha Charuma, on #MyOpinion a few weeks ago, beautifully spoke of how Winnie Mandela has yet to be effectively judged and narrated adequately by her own people. And I realised that the reason for my difficulty is in that I was suppressing the real need for me to personally write about Winnie Mandela as a black woman. It is the reason I am so uncomfortable reading about her from most sources I find. It is the reason I do not discuss Winnie Mandela with anyone whose hair would have had an easier time with a pencil under the Population Registration Act: her story is the story of many black woman. It is the story of a woman who is seemingly only contextualised as the woman behind the man or the criminal behind the murder. A story whose slant, no matter how seemingly balanced, always seems to favour the role of her being the villainous evil stepmother to a South Africa emerging from its own Armageddon; a terrible influence who, when Nelson Mandela’s young presidency was at risk of contamination, was a gangrenous limb that had to be amputated. Nelson Mandela is lauded for making such a difficult decision, but because these factions are content with the evil stepmother being vanquished from the castle so that the father can marry the sweet, quiet woman, very few allude to how being cast aside by a husband and movement she had ferociously protected and fought for half her life, pushed aside to be a silent partner, and cast in the role of a rogue based on an executive decision made at the height of a dark time, must have felt for her. Despite her actions during the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela, one fact is always conveniently forgotten by those who cast Winnie Mandela as a one dimensional being: without her unwavering resolve, her passionate resistance, her ardent appeals to the international community, her determined refusal to let the name Nelson Mandela become just another name amongst many fighting for freedom, there may not be a rich Nelson Mandela legacy.

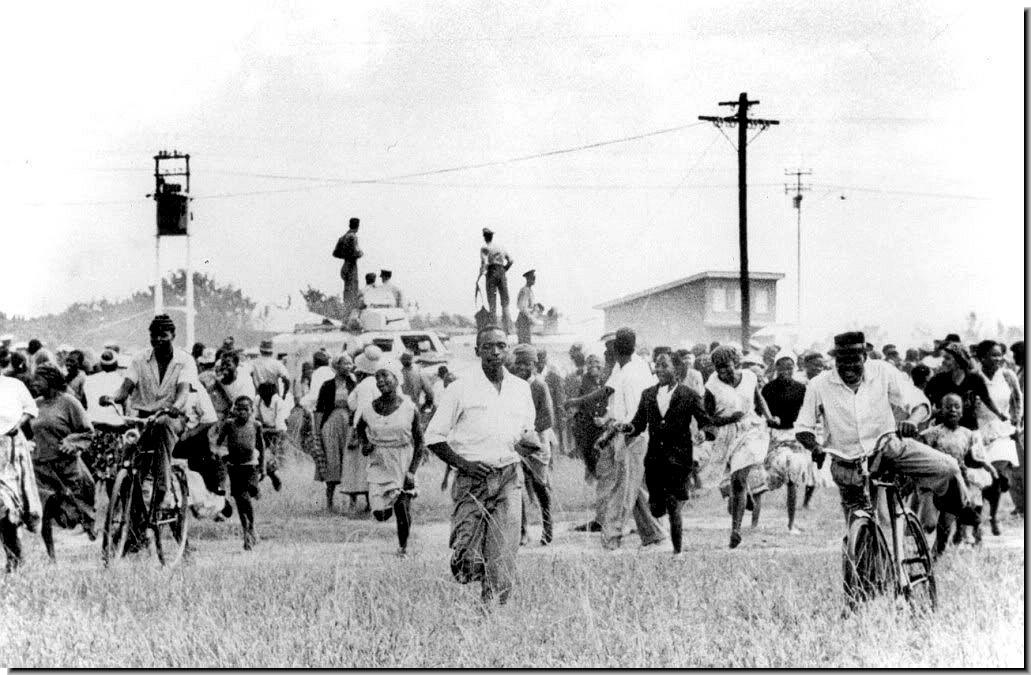

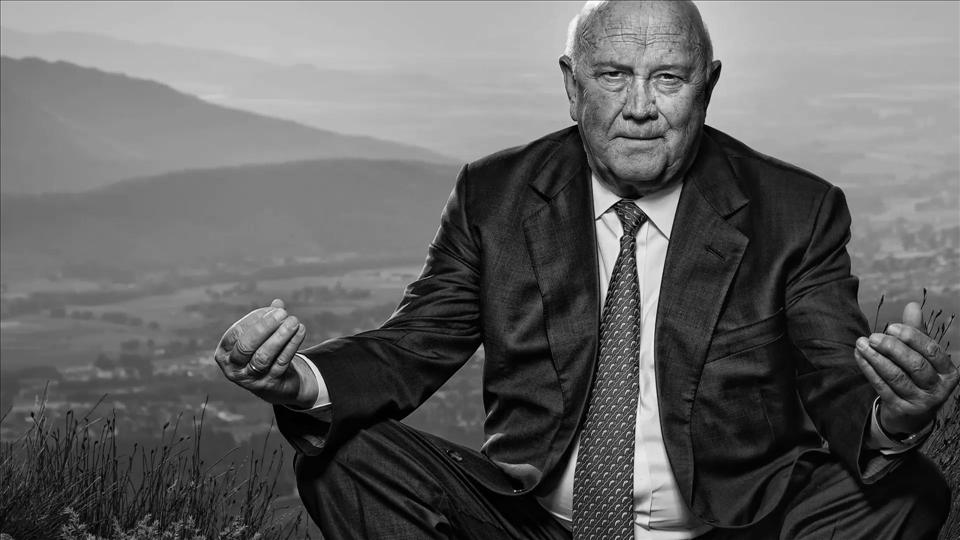

Winnie Mandela’s successes are as intrinsically woven into the fabric of the South African success story as Apartheid, yet she is reported solely as a woman who refused to apologise for actions she actually felt no remorse for, and as a human being who tries to be honest with myself, I don’t know if I would be sorry either if I were her. It is easy to judge her with the fortune of hindsight when we weren’t there ourselves. It is easy to cast a woman who had every single thing ripped from her by the inhumaneness of Apartheid into the role of malevolent delinquent because she lived a reality many of us will never understand and it is easier to vilify a black woman. We will never understand what it meant to be hunted. We will never understand what it meant to be betrayed. We will never understand what it was to find a traitor in our midst who is exactly the kind of person you are fighting for in the middle of a fight for freedom for all. Yet it is easy to stand in judgement of her because it’s convenient. No one questioned what she meant – or more importantly who she meant – when she spoke of following orders. No one considers the psychological atrocities she experienced while in solitary confinement. No one questions how FW de Klerk, who is responsible for atrocious acts against black people, can be viewed with a kinder eye within media circles, than Winnie Mandela, a woman who chose to die on her knees than live in submission.

Her story is the story of every black girl who has been mistreated because she dared to voice her opinion and refused to accede to a given role. It is the story of the African black woman who refuses to hold her tongue. It is the story of all of us who have been labelled as “trouble-makers” because we dared to be different, dared to fight back, dared to speak out in whatever capacity was applicable. She holds her head with pride as she responds to demeaning questions wanting answers for things we readily forgive white Apartheid transgressors for, because she is fortunate enough to be born with those three slaps: African. Black. Woman. She held on to her afro and kept her face free of make-up in a time when it was seen as a crime to be comfortable with your black body. Her story is that of every woman who has been made an expedient culprit while the man she fought with and for is revered, while we all forget that the celebrated Nelson Mandela was a withering representation in danger of falling into forgotten territory, until an African black woman with the will of fortified steel was forced to become someone she had never envisioned in order to uphold a fight she had no role in starting.

And that is why Winnie Mandela is so hard to write about. She is an African, black woman, who allowed herself to be used for the ends of a people, made certain she was in some way able to garner a semblance of control, and in the process, was cast in the role of antihero by a large portion of the same people she assisted. Her story is that of black women in all levels of the African landscape, black women who are undermined, bullied, victimised and undervalued not only by a system of continued oppression, but by the same men they work to protect. She represents bad girls gone good and good girls gone bad. She represents African beauty and the role African women have played as substitute mothers to other women’s children. She is a dichotomy of enforced strength woven out of struggle, and human weakness present in the building of a legacy.

She is my Mother, my aunts, my sisters and matriarchs around the continent. Women who fight every day but will never get a statue because even in the face of losing everything, they refused to submit.

She is a symbol of our strengths and weaknesses, our oppression and our abilities to rise above it all while disparaged on all sides.

She is Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela, and on this, the 26th of September 2016, I celebrate eighty years of her life. I say, even if she will never read this:

“Thank you.

Thank you for your sacrifice. I cannot imagine it was easy.

Thank you for your strength. I cannot imagine it was effortlessly won.

Thank you for your refusal to die on your knees. I cannot imagine that standing up was always painless.

Thank you for your refusal to cower to the farce of the Rainbow Nation. I cannot imagine that it was what you had envisioned.

Thank you for remaining true to your own people even when we failed to speak out in your defence. I cannot imagine that it made you popular.

And thank you for showing me that African black women should be disruptive in the pursuit for our freedom. I know it was not done alone; but I thank you for taking up the mantle and putting on that vest with an “S” on your chest, because you reminded me that we could be real-life superheroes. I will continue to fight for your true representation, because by simply being you, you fought for mine.

I can proudly say I lived in the time of Winnie Madikizela Mandela.

And what a time it was.”