Disturbing stares are central to Boitumelo Motau’s figures in Inserted Bodies, his solo exhibition that forms part of his recently awarded Blessing Ngobeni Art Prize. When traversing the city of Jo’burg on foot, eye contact is avoided and the eyes are averted. What happens instead is that we look at each other without really looking at each other. If we pause to really look, it is brief; fleeting. In the milieu, the eyes and mind dart to and fro, simultaneously taking in multiple scenarios; their permutations and functions, while trying to anticipate what lies around the corner. Pace and alertness are integral to negotiating the streets – you have to look alive, and ready to spring into a sprint at any given moment. Perception is key – you have to retreat into your third eye, have eyes at the back of your head, and have your ears function as side mirrors.

Well, for the most part anyway. On other days, a deep sense of anguish omits the usual vigilance, and a dark pall accompanies the walk. People get too close, you don’t see them coming – it is as if you are weighed down by invisible figures; spirits too dire to bear. The tall buildings standing guard look down on the unsuspecting throngs, indifferent to their strife; permitting those who devour flesh to have their way with you.

If ever there was a visual representation of these vile apparitions, they are to be found in some of Motau’s work on Inserted Bodies. While Motau has previously dealt with disfigured bodies in various forms of broken hideousness, similar to some of Dumile Feni’s work at a certain period, this time the figures are almost fully formed, though some are hunchbacked – and ancestral; observing the cyclical decay of black existence since The Glen Grey Act of 1894. The act was, “instigated by the government of Cecil John Rhodes, it established a system of individual (rather than communal) land tenure and created a labour tax to force Xhosa men into employment on commercial farms or in industry,” states the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Motau’s work is concerned with the transitory nature of the city and the legacy or lack thereof that perpetuates itself in the contemporary. It is concerned with how the Glen Grey Act set in motion the destruction of the Black family structure. We are weighed down by the lack that continues unabated, since our forebears were forced into labour in this god-forsaken city. The cycle continues in the concrete jungle, where movement and transit are in pursuit of currency. In articulating these endless scenes in motion, the figures are still – looking on in disapproval. As if multiple generational missions have been betrayed.

“When I speak about history, I am specifically speaking about the stories of the people that migrated to Johannesburg – looking back to the gold rush; to black men and women forced to leave their families to work in Johannesburg as miners and domestic workers – and to recent years, where more diverse groups have migrated to Johannesburg, seeking better opportunities,” Motau confirms.

And so we trod along, with these anxieties and among these inserted bodies that pervade our daily existence. In form and structure, the works demand to be seen; forcing us to reckon with the history and violence; current and historical. Nothing will go right anytime soon, but Motau is an astute interlocutor of times present – devoid of the niceties and illusions that seek to paint a Black existence that is anything but vulgar and inhumane.

*Motau is the recipient of the Blessing Ngobeni Art Prize, which is aimed at assisting young and emerging visual artists to launch their careers. The award provided Motau with a 12-week studio residency at Ellis House in Johannesburg.

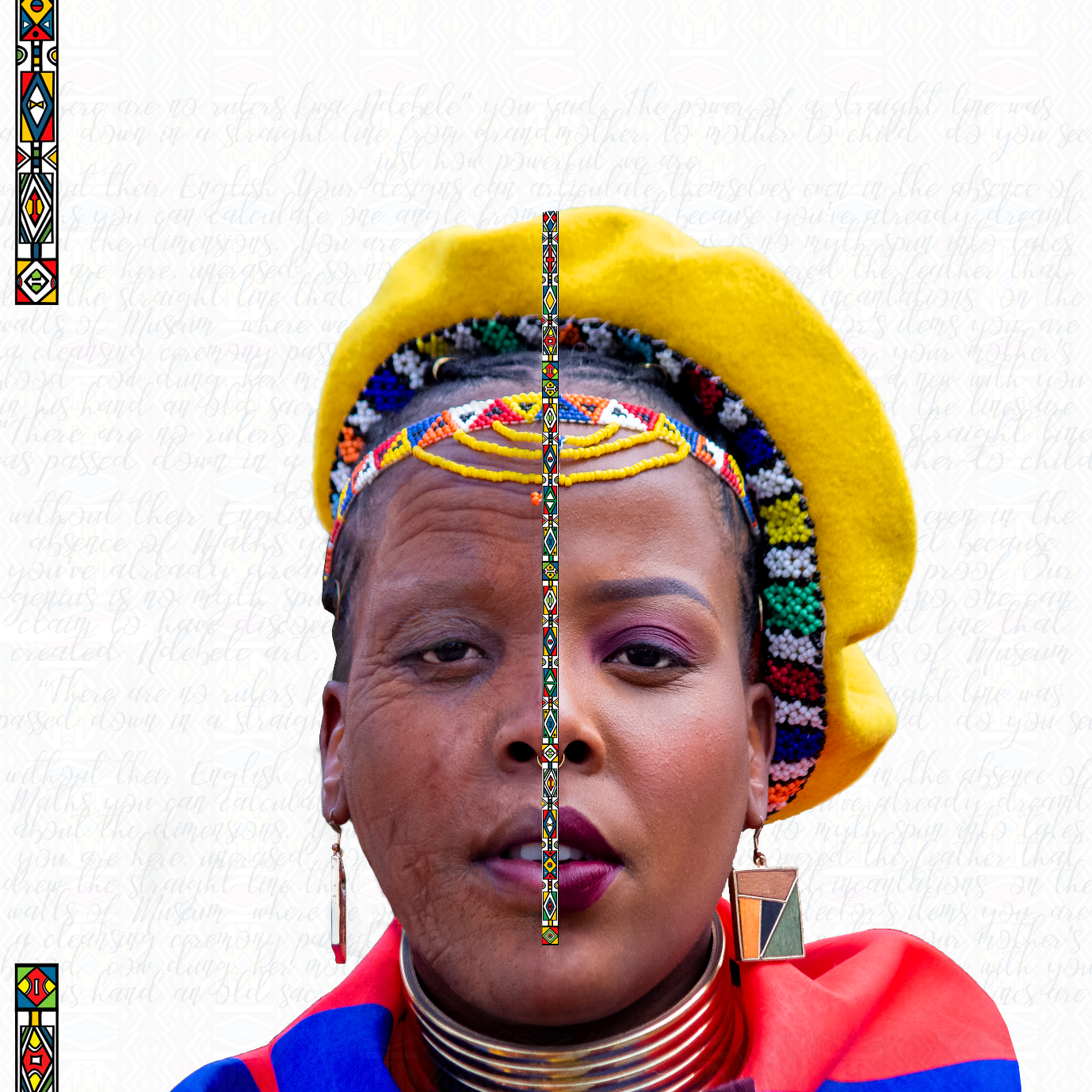

Inserted Bodies Walkabout: