Transmissions of knowledge and memory are essential in preserving indigenous narratives, traditions and languages in the face of colonial erasure and democratic disregard of indigenous cultures in this country. Where I stand, is of the position that this very preservation is a pointed gesture toward paving the way for a future where indigenous narratives are preserved and celebrated as vital contributions to our collective freedom in South Africa. As fate would have it, at a time when I have been reflecting on South Africa’s third decade of democracy, Bronwyn Katz’s latest exhibition appears at Stevenson gallery, under the title stone’s embrace, a love spiral of erosion and renewal.

The exhibition features a soetes tree as its central character. ‘Sweets’ or ‘Soetes’, Katz calls the sweet-thorn tree in their love-letter, to the Acacia Karoo tree. It is soetdoring in Afrikaans, muuka ka Setswana and umunga ngesiZulu. Bearing soetes and soils in tow, Katz’s exhibition of the metaphors in materials took me on a journey down the complex history of South Africa, particularly the legacies of colonialism, apartheid, and forced removals in Kimberley.

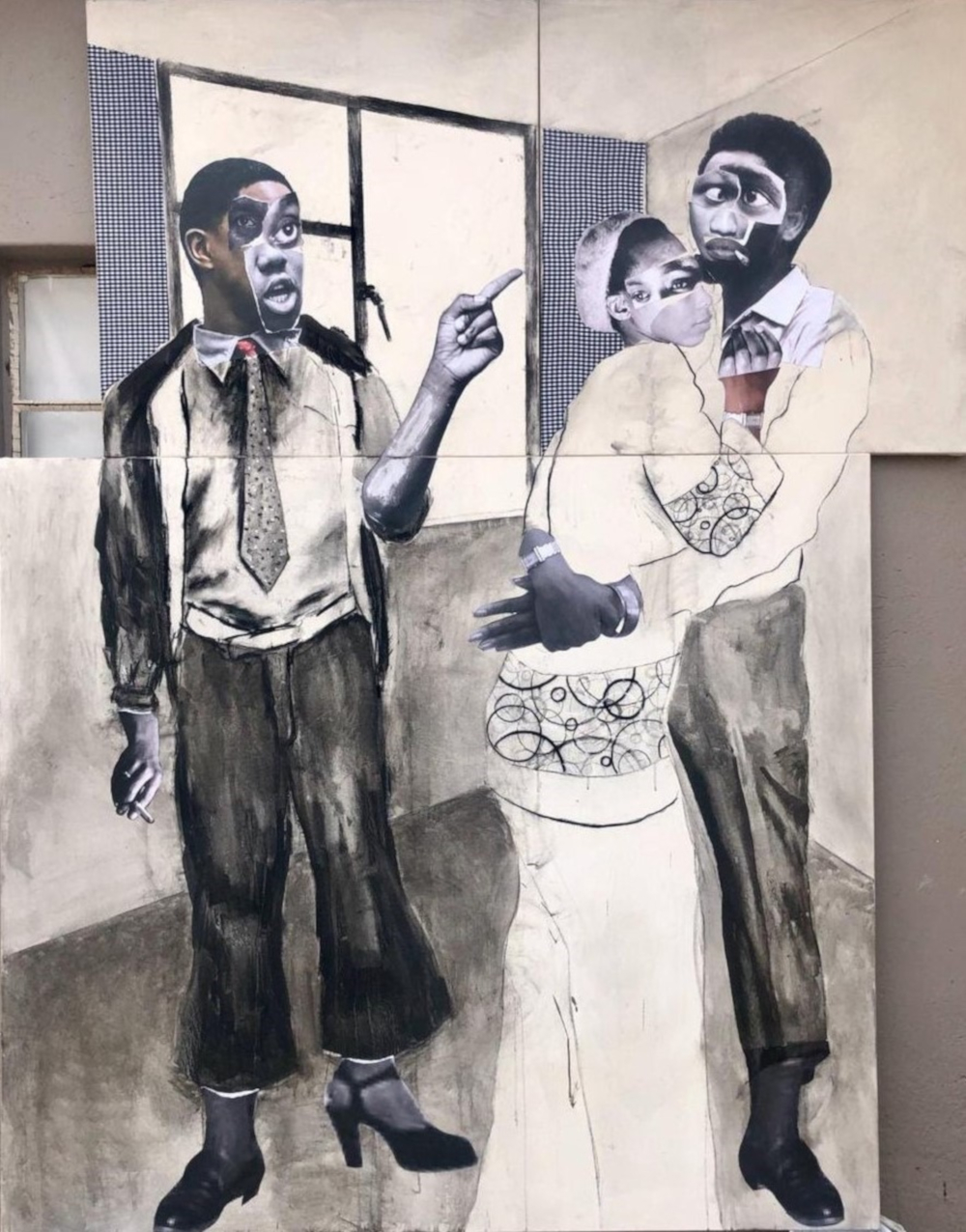

I attend the opening of the exhibition at Stevenson, Johannesburg. This is Katz’s first solo presentation with the gallery. As I enter, I am welcomed by //xū//nana (seeds of the sweet-thorn), a stellular composition at the front gallery. //xū//nana (seeds of the sweet-thorn) is a wall installation adorned with rose quartz, jasper and iron ore which Katz inherited from their father. My eyes travel between each stone. Mild steel rods connect the stones. Standing at a distance, the work appears to float on the wall, comparable to stars dancing amongst the skies. Katz references their family in Kimberley through this work, some of whom were miners, and I can’t help but see a connection to Johannesburg’s gold mining history when I consider the diamond mining background of Kimberley. Kimberley, originally established at the onset of the diamond rush in the 19th century, represents a pivotal moment in South Africa's history, where rapid urbanisation, segregation, and the exploitation of natural resources changed the landscape. In Kimberley, the establishment of townships like Greenpoint, where Katz is from, was not only the result of the Group Areas Act, but of the previous colonial, mining history as well. The forced removals under apartheid were a brutal and systematic action and Kimberley had already seen rural agricultural plus urban peoples displaced due to the 1913 Land Act and the so-called ‘betterment’ policies. In 1992, professor of Geography David Smith documented this expansive history in The Apartheid City and Beyond: Urbanization and Social Change in South Africa. In Katz’s work, the decimation of language and cultural heritage are a personal story of lasting divisions that are still felt today. By referencing the political and personal history of Greenpoint, Katz provides a critical lens through which to examine issues of erasure, beyond shame. In exploring the history of Katz’s family constellation as well as the symbolism of the soetes tree, I reflect on the complexities of South Africa's past. Our exploitative and extractive ecologies are marked by mining histories.

At the exhibition, I am beckoned by the sound of Katz’s voice, to my immediate right. I enter the gallery’s second room where I find the artist’s sound installation softly echoing from speakers suspended at the corners of the room. What I hear is a retelling of Katz’s bashfully taboo encounter with eating fruit from a soetes tree. During their walkabout, I prompted Katz and asked about the taboo in the narrative, to which they replied:

In the story I eat the fruit and then I tell my grandmother and she ‘shames’ me. She says, 'You're not starving, don't eat it!’. I had to relearn about the tree. The taboo stems from being indigenous. The tree is of the earth. The taboo stems from colonisation and apartheid, that in being from here, you are less than… that it is better to deny being of this place and to forget. It even stems down from the language, the last person in my family to speak my ancestral tongue was my great-grandmother.

Not from here can signify many things. It could be “not of the land or the earth”. What Katz does with stone’s embrace is turn their considerations regarding the colonial fragmentation of indigenous peoples into an intimate love story. Katz looks at here, where they are from, not through roots in the land as a kind of colonial ownership, but through interpersonal relations. In Katz’s sculptural prowess, here, is perhaps “a somewhere in the sky”, which speaks strongly of Katz’s constellation reference as a reference to being of your relations. In stone’s embrace a sky of rocks is passed down with the knowledge that the stone’s grounding and healing capacity is a means to locate oneself in something, somewhere, somehow, beyond the segregations. Katz's storytelling of childhood memories, to the underscore of the Atlantic Ocean, reveals a lineage of survival amidst colonial impositions.

Soetes (Sweetness), 2024 ©️ Bronwyn Katz. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam. photo: Nina Lieska

Katz’s soetes tree is additionally reflective of interdependence, where they highlight the importance of indigenous knowledge practices in fostering a harmonious relationship with the earth. Across from the central room bearing the soetes tree is the entrance to the gallery’s third, much larger room. Here, I encounter a final wall installation, titled !KhāIIaeb (Flowering season). Driftwood, blue gum, pine and black wattle are individually embraced by quartz, jasper and river stone. The scattered pieces make up a floor-to-ceiling installation that takes up the entirety of the wall. Every piece of wood, reminds me that I am of the earth, just like Katz’s beloved soetes tree. Having to come up close to see the detail, of which stone holds space for the healing of each wooden fragment, I realise how carefully Katz must have listened to these fragments to select the stone needed for each piece. What Katz shares is a process of care. In this way, the nature of what an exhibition usually does in a gallery is shifted to become an embrace of nature, an artistic continuum, rather than static products of consumerist gaze. This is what I read of their love spiral of erosion and renewal.

!KhāIIaeb (Flowering season), 2024 ©️ Bronwyn Katz. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam. photo: Nina Lieska

It would be remiss of me not to consider the materiality in this show. The exhibition's mediums are conduits of history and healers of the earth. Copper, with its ability to heal joints and conduct electricity, is a messenger, transmitting messages from stone to soil to wood. Rose quartz and jasper stones additionally known for their healing abilities, are assistants to the copper. Each stone is a carefully considered inclusion on Katz’s part. By working with these materials, Katz not only honors their ancestors but also invites visitors of the exhibition to be embraced by the pieces and to reflect on their own connections to the past. Through Katz's work, I am reminded of the interconnectedness of all life forms. Stones, once seen as inert objects, renew their connection with ancestors and their activity as time capsules. One of the most compelling aspects of Katz's work is the use of materials as intergenerational transmission of knowledge and memory – particularly in relation to language.

Their gesture of naming the artworks in the !Ora language is a deliberate choice that asserts the absent-presence of South Africa’s indigenous languages at this 30-year milestone of democracy. I look to the meaning of milestone, meaning ‘a marker to locate distances’ and see this compelling exhibition as an embrace of our shameful neglect of certain indigenous languages and practices, leading to their erosion. Indigenous people have continued to suffer erasure in our 30 years of democracy, and for them the issue of land redress remains a fight for democratic recognition.

Katz’s first solo exhibition in Johannesburg serves as a form of aesthetic cultural resistance, challenging the narrative of apartheid’s historical superiority in South Africa. Katz’s work maps possible ways forward, into the next 30 years. With a loving embrace of similarity and difference, can South Africa walk toward a particular kind of healing that includes South Africa’s indigenous othered? This exhibition calls for a confrontation with the lost connections of the past. I was invited to work towards a kinder, collaborative, even if still extractive, relationship with the land.

Dineo Diphofa is a curator, researcher and writer who works at the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD) at the University of Johannesburg.