“...And now we have come to the nucleus of the problem we have before us at this time. Today one finally has the right and even the duty to be, above all things, a revolutionary doctor, that is to say a man who utilizes the technical knowledge of his profession in the service of the revolution and the people. But now old questions reappear: How does one actually carry out a work of social welfare? How does one unite individual endeavour with the needs of society? We must review again each of our lives, what we did and thought as doctors, or in any function of public health before the revolution. We must do this with profound critical zeal and arrive finally at the conclusion that almost everything we thought and felt in that past period ought to be deposited in an archive, and a new type of human being created…” – Dr Ernesto “Che” Guevara to Cuban Militia on Revolutionary Medicine (16 August 1960, Havana)

To be healthy presupposes not only physical wellness, but also the ability of the spirit to be one with nature and its gifts to humanity. To love nature, as it gives life and to cherish life as it sustains nature. It is this symbiotic relationship between love for what is good (justice) and life itself that form the cornerstone set of principles of what we come to know as social medicine. Revolutionary healthcare therefore is premised on the goodness of humanity and a radical demand for social justice. The Gentile Paul laments to the Corinthians that the body is a temple of God suggesting the sensitivity with which the human body needs to be handled and cared for. This is also true for Mother Earth which is nature; humanity needs to handle her with circumspect as the body which all life depends upon for nutritional development, survival and sustenance. Healthcare is a human good, a social good and a life giver.

Dr Guevara further opines:

“...the life of a single human being, is worth a million times more than all the property of the richest man on earth...”

These few words best essentialize the radical appreciation of life, nature and the attitude towards healthcare in Latin America. Social medicine is anchored on the fundamental concepts of social justice, nutrition and good hygiene practices. On the idea of free universal preventative healthcare for all, irrespective of creed or background. Participatory and decentralized from political bureaucracy and private healthcare. A revolutionary doctor understands that in order for people to thrive they must work together for common good; there is equality between the patient and the doctor. These fundamental principles are also social determinants for access to good healthcare. A revolutionary doctor is not merely concerned with pain. His concern is life in the holistic sense; Where do you live? In what type of environment? Your class standing in society? Do you have access to healthcare? Nutrition?

With global capitalism at an impasse, the response to disease, sickness and healthcare argues for the creation of a new generation of doctors. Post World-War 2, countries embarked on the creation of social security for their citizens. Human rights, social rights, the right to health, shelter, food and to life became the cornerstone through which building a new society would be modelled. The atomic bomb was replaced by investments on development through which the League of Nations (now United Nations) had the international duty of upholding peace, stability and sustainable development. This was followed by the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions, wherein the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were established to facilitate the financing of nation building torn apart by the war. The World Health Organization was also established to facilitate the same vision for international healthcare on 7 April 1948. The same year the Nationalist Party took power in South Africa, in which Boer capitalist nationalism and Herrenvolkism outlined apartheid as the model of the country’s path for development.

Latin America, a continent ravaged by colonialism, capitalist plunder and underdevelopment caused by Western powers like Spain and the United States of America, went on to carve a philosophy for public healthcare that brought the continent into conflict with the bullies of the West. Dr Salvador Allende, the first ever Latin American Marxist physician to inherit state power through the Chilean Socialist Party in 1970 is arguably a concrete expression of this conflict. Yet, as the world battles with the global healthcare pandemic of Covid 19, his radical ideas on social medicine emerge as the only way out for the international healthcare fraternity. The life of one human being is worth a million times than the property of the richest man on earth!

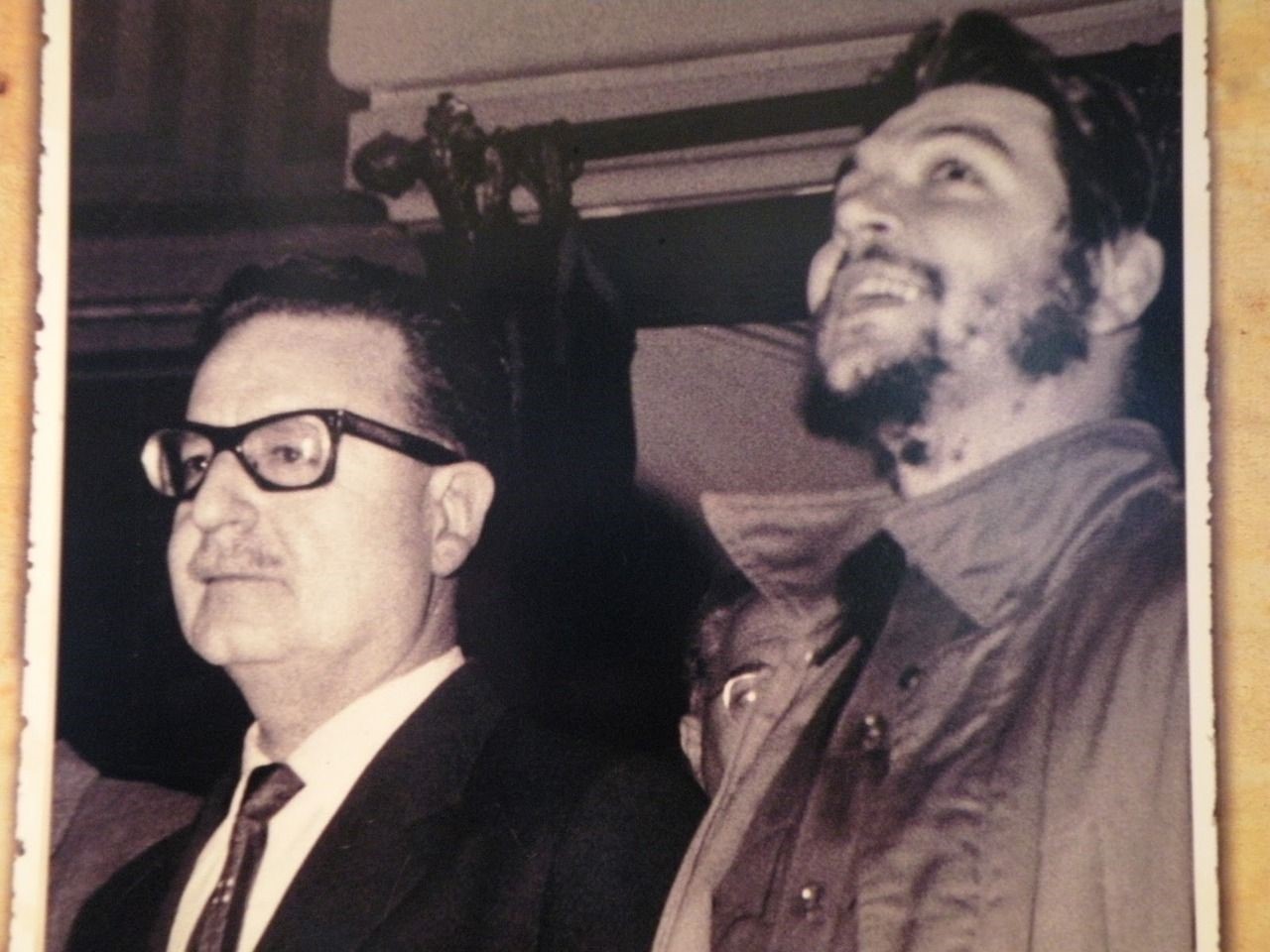

•Dr Salvador Allende; Revolutionary Physician & Latin America’s 1st Marxist State President

Born into an upper-middle-class family, Dr Allende received his medical degree in 1932 from the University of Chile, where he was a Marxist activist. He participated in the founding (1933) of the Chilean Socialist Party. After election to the Chamber of Deputies in 1937, he served (1939-42) as minister of health in the liberal leftist coalition of President Pedro Aguirre Cerda. Allende won the first of his four elections to the Senate in 1945. Allende ran for the presidency for the first time in 1952 but was temporarily expelled from the Socialist Party for accepting the support of the outlawed communists; he placed last in a four-man race. He ran again in 1958 - with Socialist backing, as well as the support of the then-legal communists - and was a close second to the conservative candidate, Jorge Alessandri. Again with the same support he was decisively defeated (1964) by the Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. For his successful 1970 campaign Allende ran as the candidate of Popular Unity, a bloc of socialists, communists and radicals. Lacking popular majority, his election had to be confirmed by Congress, in which there was strong opposition from the right. Nevertheless, it was confirmed on October 24, 1970, after he had guaranteed support to 10 libertarian constitutional amendments demanded by the Christian Democrats.

Inaugurated on November 3, 1970, Allende began to restructure Chilean society along socialist lines while retaining the democratic form of government and respecting civil liberties and the due process of law. He expropriated the U.S.-owned copper companies in Chile without compensation, an act which set him seriously at odds with the U.S. government and weakened foreign investors’ confidence in his government. His government also took steps to purchase several important privately owned mining and manufacturing sectors and to take over large agricultural estates for use by peasant cooperatives. In an attempt to redistribute incomes, he authorized large wage increases and froze prices. Allende also printed large amounts of unsupported currency to erase the fiscal deficit created by the government’s purchase of basic industries.

Medical Internationalism: Dr Ernesto “Che” Guevara & Cuban Culture in Post¬-Revolutionary Years

The nationalist movement that Jose Martí had started in his exploration of social equality and national pride became Dr Enersto Guevara’s plan to create an army of doctors. After the revolution of 1959, the Cuban people had high expectations. Castro and Guevara built on Martí’s idea of a “New Cuban Man” and united it with their internationalist plans. They prioritized health care, education, and aid. The marriage of these ideas resulted in a fledgling system of socialized, internationalist medicine that was founded on goodwill, aid, and prestige, in hopes of receiving influence, credit, and more trade options (Feinsilver, 2008). Healthcare inside Cuba follows Medicina General Integral, or “General Medicine,” an approach that focuses on universal preventative healthcare. Using small teams known as consultorios, one doctor and one nurse are assigned to different regions across the country (Johnson, 2006). The teams make regular visits to homes and communities with an emphasis on equalizing medical access and increasing overall health (Brouwer, 2009). In 2004, the Cuban National Assembly passed a resolution that promised all citizens the right to access medical care (Johnson, 2006). By the end of that year, Medicina General Integral was providing health services to 99% of the Cuban population, approaching Castro, Guevara, and Martí’s goal of social and medical equality for all Cubans. The tradition of Cuban medical internationalism began in 1963, with Cuba sending medical aid to Algeria during their revolt against French colonialism. Cuban health professionals provided the only medical aid to the rebel fighters, and were thus a significant support in the Algerian independence struggle (Huish & Spiegel, 2008). Later that year, the United States embargoed Cuba during the height of the Cold War. In spite of this, Cuba began to use medical internationalism as a means to form and strengthen ties with other nations. As Fidel Castro stated on Cuba’s medical presence after the Haitian earthquake of 2010, “we send doctors, not soldiers” (E. Kirk & J. Kirk, 2010). Scholars describe Cuba’s burgeoning international “medical diplomacy initiative” as a form of foreign policy (Feinsilver, 2008). Cuban medical internationalism is structured around the concept of solidarity, defined as “an intentional act of cooperation between two nations in order to produce benefits for both.” The Cuban government has described their system of internationalism as a repayment of their debt to the international allies who provided assistance in the early years of the Revolution. (Feinsilver, 1989). While Cuba’s internationalism varies from country to country, it can be categorized into three forms of solidarity: remuneration, bartering, and investment. In the first, remuneration, countries directly pay the Cuban government and its medical professionals, thus providing Cuba with desperately needed foreign currency. This set up can be seen in countries such as Qatar, to be further explored later in this paper. The second category is solidarity bartering, in which Cuba receives preferred trading privileges for certain resources. This model is utilized by Venezuela, as well as Bolivia, Guatemala, and the Gambia. The third category is solidarity investment, in which the host countries offer no payment or trade to Cuba, but still receive Cuban medical 9 assistance. This category is utilized in economically devastated countries, such as Haiti after their 2010 earthquake. In these circumstances, outreach is paid for by the Cuban government, or by a third party country, such as Norway, which provides medical equipment to Cuban doctors in Haiti and Taiwan. (Huish, 2014). Cuba’s system of solidarity isn’t altruism, nor is it imperialism. These arrangements are an alternative to charity or aid missions, as it benefits both the donor and the recipient nation.

Exporting Medical Culture: The Venezuela Model

Socialized medicine as argued by Lenin “is the keystone to the arch of the socialist state”. Revolutionary healthcare in Venezuela was heralded by the advent of 21st century socialism which emerged as a result of Partido Socialista Unitas de Venezuela (PSUV) winning state power in Venezuela. The Latin American Collective Healthcare Movement has always been sustained by revolutionary politics, this is the difference between the Western value system of healthcare and Latin America which is founded on solidarity, compassion and social justice. For revolutionary medicine to exist, there must be a revolution to begin with. Cuba’s culture¬-based healthcare falls directly in line with Cuban values of solidarity and the repayment of debt through humanitarian work. For example, Cuba has a large medical presence in Venezuela. Starting in 1999, Cuban-¬Venezuelan relations grew following a series of counter revolutionary efforts that put Venezuela in need of medical personnel. Their cooperative program was solidified in 2003 with the goal of providing resources to both countries (Blue, 2010). Under this agreement, Cuba provides Venezuela with medical professionals in exchange for oil at preferred credit rates (Huish, 2014). Cuba receives 90,000 barrels of discounted petroleum daily (Yanez, 2005). In exchange, 20,000 Cuban health personnel have been sent to work in primarily poor, rural areas of Venezuela. Venezuelans have access to over 7,000 offices and clinics where they are provided with Cuban medical services for free (Berlatsky, 2013). Taking inspiration from the Cuban healthcare model, the former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez developed a second Latin American School of Medicine in Caracas, Venezuela, in 2005 with the intention of doubling the number of medical graduates. (Kirk, 2007). Indeed, Cuba and Venezuela together intend to train 100,000 doctors at no cost for the students to be sent to the developing world. In 2011 alone, nearly 50,000 doctors were trained in the two countries, all of whom are encouraged to continue Dr Salvador Allende social medicine and Dr “Che” Guevara’s theme of revolutionary medicine to serve their communities. Students are taught with an emphasis on preventive medicine, and placing community needs before individual ones (Kirk, 2012). Venezuela has provided additional funding to sponsor Cuban medical professionals abroad. This funding has led to a major increase of Cuban medical international presence, thus providing Cuban health workers opportunities to earn hard currency while working abroad (Blue, 2010). In addition, “Operation Miracle,” a joint project of Venezuela and Cuba, restores sight to poor Latin Americans at no cost. A case study for the world on how optometry and dentistry can be fashioned with needs of healthcare whilst maintaining the equality between the doctor and the patient. The effort is funded by Venezuela’s petroleum capital, and utilizes medical professionals from Cuba to perform eye surgeries and provide eye care to the poorest communities in the Caribbean and South America. (Kirk, 2007). This project has restored sight to over two million people since it began in 2005 (Kirk, 2012). The comprehensive health care system set up in Venezuela mirrors its equivalent in Cuba. In 2006, a study by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) showed that of the 171.7 million medical visits Cuban doctors held in Venezuela, 67.9 million were in community locations such as schools. Of those 67.9 million, another 24.1 million were held in homes (Feinsilver, 2008). This approach embodies a Cuban value of healthcare revolving around the patient. The core values that support Cuba’s own health system are reflected in their foreign projects. As seen in the Cuba¬-Venezuela doctors ¬for ¬oil deal, Cuba does not merely export thousands of doctors to foreign countries without any plan or structure. The unseen deal in this negotiation is the export of Cuban values into the Venezuelan healthcare system. Cuban doctors are not being sent to only provide aid-their main job is to train Venezuelan doctors, 40,000 to be exact (Feinsilver, 2008). While Cuba’s work in Venezuela is emblematic of Cuban aid abroad, it is by no means the only example. Cuba has healthcare projects set up in more than 100 nations abroad, serving mostly the developing nations.

Global healthcare & Cuban responses: From natural disasters to HIV, Cancer, Hepatitis, Cholera, Ebola now COVID 19

“...The doctor, the medical worker, must go to the core of his new work, which is the man within the mass, the man within the collectivity. Always, no matter what happens in the world, the doctor is extremely close to his patient and knows the innermost depths of his psyche. Because he is the one who attacks pain and mitigates it, he performs an invaluable labour of much responsibility in society…” – Dr Guevara; Revolutionary Medicine

These words echoed when announcements that the world would go on an unprecedented shutdown due to a novel Covid-19 virus. This catastrophe unheard since the Great Depression which garnered an impact on the domestic economies akin to that of the 2007/8 global recession. A situation which forced major governments to tap into alien ideas usually rejected in free market economy societies. Across the world governments are nationalizing healthcare, Central Banks printing money to sustain ailing economies, help citizens cover debts, mortgages, loans and salaries. Ideas dubbed extreme by the global capitalist order in normal pandemic free everyday life. In South Africa, the domestic healthcare situation calls for concern in many facets. As the government rolled out pro-market measures to deal with the virus, the debate insisting on early treatment of Covid virus infected persons unfolded across the local sphere. Ekurhuleni Mayor Mzwandile Masina, the Regional Chairperson of the ANC in the said domain waxed lyrically about the need for Cuban intervention to the problem. As expected, South African media owing to its loyalty to the CODESA property owning class ruling South Africa, ridiculed, belittled with many calling him an off-shooter who knows nothing about medicine. This intervention in the local sphere by Mayor Masina took place under a particular context in which the Latin American island of Jose Marti had steady been responding to calls from global governments requesting Cuba’s revolutionary medical diplomacy to battle the virus. Cuba and the national liberation movement in Africa are historical forces against global imperialism which treats healthcare as a commodity.

It was Cuba who fearlessly stood by the former Saint-Domingue French colony, famous for the largest and most successful slave revolt in the Western Hemisphere. The now sovereign state of Haiti, when it was ravaged by natural disaster in 2010. It was Cuba who stood with Haiti when Cholera broke out in the country. It was still Cuba which became the first country to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV virus. The same Cuba which makes its own medicine boasting a people centred biotechnology industry that saves lives worldwide instead of making profit or bomb. Fidel Castro’s emblematic words in 2010 do suggest that the second revolution in the Latin American healthcare superpower is biotechnology. To date it boasts the highest patient to doctor ratio in the World. A country with 60 years of sanctions, warfare and economic degradation by the US.

The Latin American perspective on healthcare is anchored on revolutionary politics in that medicine and science are seen as pivotal instruments for betterment of humanity as opposed to commercialization and control by big pharmaceutical companies and private equity. Hence it is no surprise that in developing nations, socialist Cuba is always at the doorstep of mediating pain. The first vaccine to treat hepatitis was manufactured in Cuba by local scientists and biotechnologists. The vaccine is now distributed in over 30 countries. The vaccine for lung cancer for the first time in 2018 got the United States eager to collaborate with Cuba for the creation and mass distribution of the vaccine as the US is a country ravaged by crass consumerism of cigarettes. This is also carved in a documentary which is set to be released in 2021, something which remains to be seen given Donald Trump’s new set of embargoes against the island.

Despite the deliberate ruin, which if averted could turn Cuba; one of the last remaining Socialist state of the Cold War era into a trade giant exporting healing as opposed to sickness of the US & Bill Gates funded World Health Organization, CDC. Countries like Qatar, the middle-east oil rich country with the highest per capita GDP in the world have expressed full confidence in Latin American biotechnological prowess. Qatar pays Cuba large sums of money for medical services, pioneered by Fidel Castro’s exemplary leadership, the partnership cemented the first Cuban hospital to be built outside Cuba- found in the Northern region of the country staffed with over 400 medical professionals. Ebola in Africa was mitigated by Cuban internationalism, when the World Health Organization was gambling with lives, the vanguard of global healthcare in the developing world came in and stabilised the situation.

It was not a misnomer therefore for Mayor Mzwandile Masina to call on Cuba against the threat of Covid 19 in South Africa. The state owned biopharmaceutical industry in Havana which holds 1 200 international patents, and sells medicine and equipment to over 67 countries. We often hear less about this ground-breaking BioCuba Farma which manufactured 22 medicines against the novel Covid 19 virus. These medicines have been the backstory of how China successfully dealt with the virus which closed down hospitals in Wuhan in a speed of light. Cuban doctors are today stabilizing the situation, which for the first time has seen the country record the highest recovery rate of over 16 200 patients, with a record of 925 recoveries by end of March- including a 101-year-old man. Cuba is fighting for the lives of people in Italy alongside its historical allies in China and Russia. This is the same for Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Jamaica, China, Qatar, Spain; proving that the ideas of Dr Allende and Dr Guevara are more powerful than money.

Conclusion

Western media with its pro-Yankee capitalism and World Health Organization agenda will never celebrate the strength of socialized medicine as it is a threat to their profits sustained by big pharmaceutical companies together with their nutritional counterparts like Monsanto, Coca Cola. Emerging geopolitical alliances like the BRICS countries need to extend their base in configuring Cuba as part of BRICS. A reconfigured BRICCS, which is Brazil, Russia, India, China, Cuba and South Afrika will go a long way in titling the scales for third world development. China with the economic base, Russia with the military and economic might in Europe, India as the third largest Asian economy, Cuba with its commanding biopharmaceutical prowess and South Africa’s industrialization; largest in Afrika, would go a long way in fighting rescuing global healthcare from profit crazed first world countries. Latin America has shown that healthcare can no longer be relegated into lower annuls when measuring social progress. GDP, GNP might measure economics, trade and inequality; the success of Venezuela’s Mission Barrio de Adentro, established by the late revolutionary Hugo Chavez shows that Latin America carries the mantle of universal, preventative public healthcare globally. A reconfigured BRICCS - with Cuba as the international vanguard for science, healthcare and biopharmaceutics, founded on love, equality and social justice. Where one life matters million times more than the dollars of the richest man on earth!

Larga vide – Salvador Allende! Larga vide- Augusto Sandino! Larga vide – Enersto Guevara! Larga vide- Hugo Chavez!

Viva Fidel!

REFERENCE LIST

Berlatsky, N. (Ed.). (2013). Opposing Viewpoints Series: Cuba Opposing Viewpoints. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press.

Blue, S. A. (2010). Journal of Latin American Geography: Cuban Medical Internationalism: Domestic and International Impacts. University of Texas Press.

Brouwer, S. (2009). The Cuban Revolutionary Doctor: The Ultimate Weapon of Solidarity. Monthly Review.

Brouwer, S. (2011). Revolutionary doctors: How Venezuela and Cuba are changing the world’s conception of health care. Monthly Review.

Feinsilver, J. M. (1989). Cuba as a “world medical power”: The politics of symbolism. Latin American Studies Association. 17

Feinsilver, J. M. (2008). Cuba’s medical diplomacy. In M. A. Font (Comp.), A changing Cuba in a changing world (pp. 273¬286). New York, NY: Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies.

Guevara, E. C. (Presenter). (1960, August 19). On revolutionary medicine. Speech presented in Havana, Cuba.

Huish, R. (2014, October). Why does Cuba care so much? Understanding the epistemology of solidarity in global health outreach. Halifax, Canada: Dalhousie University.

Huish, R., & Spiegel, J. (2008, June). Integrating health and human security into foreign policy: Cuba’s surprising success. Pluto Journals.

Johnson, C. (2006). Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies: Vol. 61. Health as culture and nationalism in Cuba.

Kirk, E. J., & Kirk, J. M. (2010). Cuban medical cooperation in Haiti: One of the world’s best¬kept secrets (Research Report No. 1).