“How indeed would a living understanding come to those, who have fled knowledge of the source?” (Ayi Kwei Armah in Two Thousand Seasons, 1973, p xvi. My italics).

The fundamental distinction between a Civil Rights movement such as the African National Congress, and a liberation movement like Poqo, lies in the status of white settlers and apartheid. The mythologisation of apartheid by promoting it as the main problem in liberation politics and history in conqueror South Africa (Ramose 2018) is the persistent intellectual obsession of the Congress tradition. A trenchant contestation and rejection of apartheid as the fundamental antagonism in the history of the struggle for national liberation is the defining trait of a liberation movement and liberation intellectual production. Due to the triumph of the Civil Rights movement of the ANC in 1994, the Congress tradition as an ideological and intellectual paradigm has attained hegemonic status with the help of white liberals (Mafeje 1998). At the very origin of the Congress tradition is the embrace and propagation of the Freedom Cheater (Pheko 2012). This is why the Congress tradition is premised on Charterism (Raboroko 1960). Adopted in reaction to the dominance of the so-called Afrikaner nationalism in 1955, the Kliptown Charter (Sobukwe 1958) is the core of Charterism, which centralises apartheid as the main problem. Liberal non-racialism (Soske 2017 & Dladla 2018) as an antidote to the rabid and clumsy racism of the apartheid regime is encapsulated in the Congress of the People’s annoying fixation with the naïve fantasy of South Africa belonging to all who live in it, both black and white. Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh is an organic product and a “bright” example of the triumph of Desmond Tutu’s curse of blacks and whites belonging together in South Africa, literally.

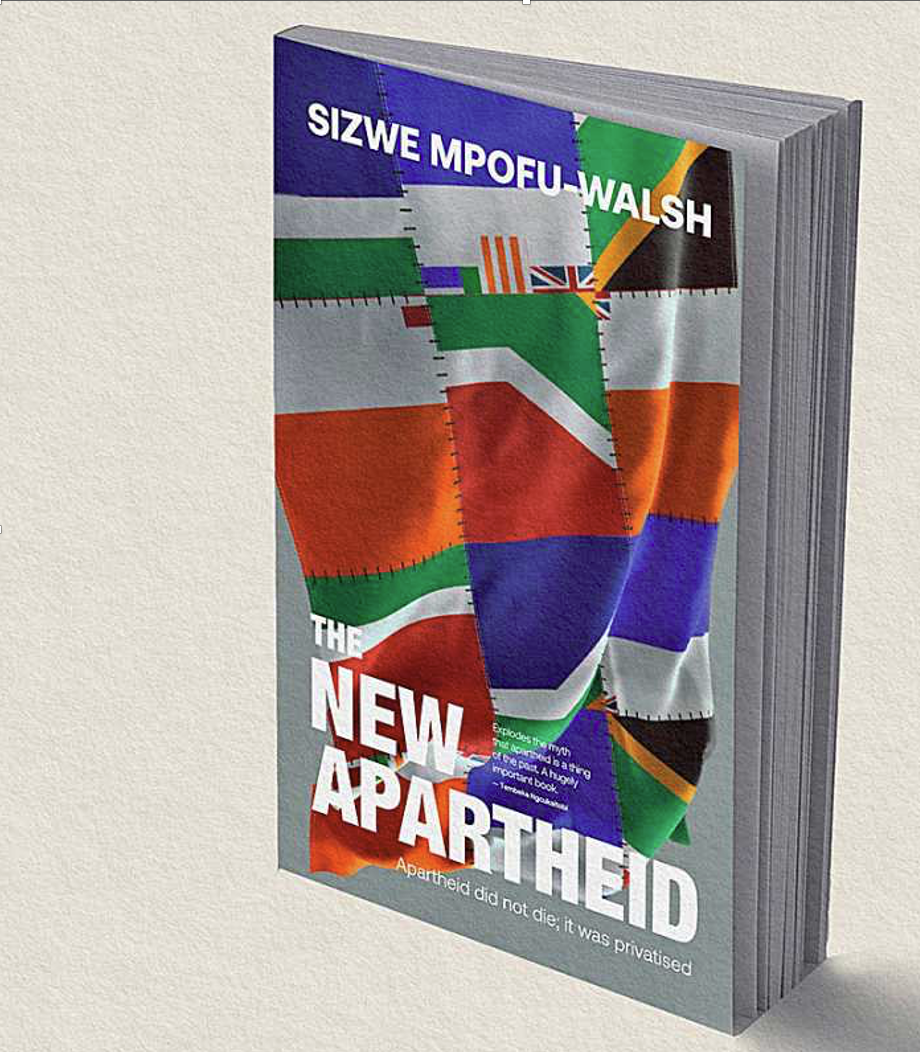

While the Congress of the People was preoccupied with the old apartheid, Mpofu-Walsh and his fellow Charterist intellectuals are obsessing about the new apartheid in “post-Apartheid” South Africa. Having written a book entitled Democracy & Delusion: 10 Myths (2019), in which he debunks what he considers to be myths about the so-called post-apartheid South Africa, Mpofu-Walsh is back again, only this time he is reinventing two myths. This first myth is about the centrality of apartheid as the problem in liberation politics and history, while the second one is about the ANC being a liberation movement. This is how Mpofu-Walsh (2021: 178) reinvents the first Charterist myth: “Defining a central social problem takes generations. In hindsight, the struggle against formal apartheid appears coherent and premeditated. But identifying apartheid as the problem took eternities of debate, struggle and reflection.”. Within the Africanist tradition as the opposite of the Charterist tradition, Peter Raboroko has debunked Mpofu-Walsh’s two myths in a piece called The Africanist Case (1960). The Africanist tradition, which was later called the Azanian tradition, broke away from the Civil Rights logic of the ANC in 1959 due to the Charterists’ betrayal of the fundamental question of historic justice: namely to whom does the land belong? Anton Lembede and Robert Sobukwe later emphasised the idea that Europeans are alien conquerors who dispossessed the Indigenous people of their land. And this land dispossession had taken place since 1652, and not 1948, making the horrible date of 1652 fundamentally important in the Africanist tradition of Lembede and Azanian tradition of Sobukwe and Biko. This implies that the fundamental problem is not apartheid, be it old or new, but conquest in the form of land dispossession since 1652 in wars of colonisation (Ramose 2007). In the book under review, entitled The New Apartheid (2021), Mpofu-Walsh promotes the delusion and first myth of apartheid as the problem, and the second myth of the ANC as a liberation movement. This is how Mpofu-Walsh (2021: 23) reinforces his second Charterist myth: “Furthermore when the liberation movement was nationalised, it assumed apartheid’s debts. These debts further constrained ANC policy choices and limited fundamental reform.” According to Mpofu-Walsh, his book The New Apartheid posits that apartheid did not die, it was privatised. The book investigates the afterlife of apartheid, which was made new by being privatised through the market logic of neoliberalism. The power of the State was diminished by the dominance of private actors. It is in this sense that Sizwe’s fellow Charterist intellectual comrade, namely Tembeka Ngcukaitobi, argues in the blurb of this book that it, “explodes the myth that apartheid is a thing of the past.” From an Africanist Tradition’s position this “explosion” is pointless, since apartheid was never the primary problem, but a mere regime invented by Dutch settlers who, under the delusion of indigeneity called themselves the Afrikaners. These delusional architects of the regime of apartheid merely reconfigured white settler colonialism, which commenced with conquest in the form of land dispossession and intellectual warfare (Carruthers 1999) in 1652 in wars of colonisation (Ramose 2006). It is only Charterist intellectuals like Mpofu-Walsh and Ngcukaitobi and their ideological victims who see the need to “explode” the myth of apartheid being a thing of the past. White settler colonialism and white supremacy in South African politics preceded apartheid and transcended it in the so-called post-apartheid South Africa. Apartheid as a political regime of Dutch settlers was just a clumsy manifestation of white supremacy. This regime is not the problem, rather, white supremacy is the main antagonism. White supremacy does not need apartheid. This is why white supremacy has outlived the regime of apartheid under liberal constitutional democracy in the current so-called new South Africa. White liberals (Mafeje 1998) like Hellen Zille and Merle Lipton (2007) know very well that apartheid as a clumsy political regime was too costly for white supremacy, and this is why they had to intervene ideologically in 1994… to secure the afterlife of white supremacy under a liberal constitutional democracy, which predictably is celebrated by both Mpofu-Walsh and Ngcukaitobi in their Charterist propaganda. So why obsess about just a regime of white supremacy and not white supremacy itself? In promoting the two myths, of apartheid as the problem and the ANC as a liberation movement, Mpofu-Walsh indulges in Charterist delusions throughout the book.

The book is divided into five sections, namely Space, Law, Wealth, Technology and Punishment. For someone who obsesses about apartheid, the section on Space is an unoriginal but well-presented summation of the racist production of social space by the apartheid regime. The section on Law is by far the most rewarding portion of this myth-making book. Mpofu-Walsh's criticism of the two schools of constitutionalism, namely the triumphalist which is advertised by his fellow Charterist intellectual Ngcukaitobi (2018) and the abolitionist as “forged” by Ndumiso Dladla (2018) and Joel Modiri (2018) is indicative of his commendable yet ultimately unsatisfying comprehension of legal philosophy. His critical point about the two schools’ naïve belief in the power of law is quite interesting. Sizwe’s legal and constitutional scepticism and critique of the legalism of the constitutional abolitionists and triumphalists is by far the only important thing about the entire book and its ridiculous underlying argument about apartheid. This is how Mpofu-Walsh (2021:68) states it: “Both constitutional triumphalist and constitutional abolitionist overestimate law’s potential for transformative change. This belief in legal centrality is not uncommon among lawyers.” It is interesting to see a Charterist intellectual mythmaker like Mpofu-Walsh engage with the Azanian tradition honestly by citing relevant scholars and in the process debunking the myth of legalism in these constitutional schools. This is the reason why we need a paradigm shift from the legal studies of the Azanian tradition and its radical liberalism (the objective of converting whites to Abantu ala Sobukwe’s African tree) to a Garvey-inspired Africanist war studies paradigm which will aim at whites physically, rather than just their institutions of war like law. Law and democracy are just institutional extensions of a race war by other means. On the premise of an uncompromising battle cry of Africa for the Africans, ala Lembede’s Africanist Tradition, the main objective of the Africanist war studies paradigm is to eliminate whites, as opposed to fighting against what they create in the process of a race war they have declared against the African race for “two thousand seasons.”

Contrary to Mpofu- Walsh’s Charterist mythmaking about apartheid and the ANC, from an Africanist war studies paradigm, the fundamental problem is whites (the white problem as opposed to the absurd racist native problem) and the race war they have declared against the African race. This is something that Poqo as a liberation movement understood. The Africanist war studies paradigm seeks to extend this in the form of liberation intellectual production. The dangerous abstract humanism underlying both moderate and radical black liberalism, of separating the enemy from the system of oppression and exploitation, and attacking only the system, must be abandoned by the African race if it is to survive as the original and chosen race. Given the ideological flipflopping of Tshepo Madlingozi (who fails to embody the essence of his name), we cannot classify him under the Azanian tradition, but we can credit him as an influence on Mpofu-Walsh's first myth of apartheid as the problem. Mpofu-Walsh is clearly familiar with the scholarship of Madlingozi, especially his article on Social justice in a time of Neo-apartheid constitutionalism, as he cites in the book. The transition from neo- to new is not a long journey to apartheid mythmaking for Mpofu-Walsh.

The Wealth section is also interesting. This is the section which foregrounds the privatisation of apartheid. It delves into the rise of market logic within apartheid, and how it affected the governance of the ANC in the “post-apartheid era” in terms of policy and debts. While in the section on Law Mpofu-Walsh demonstrated a shallow but commendable grasp of legal philosophy, the section on Wealth is a manifestation of his limited comprehension of the history of economic thought. His discussion does not show a solid grasp of the literature on the origin of neoliberalism. Merely quoting Von Hayek is not sufficient. Ludwig Von Misses, Mont Pellerin Society, the Austrian School of Economics, the German historical school and the Chicago School of Economics and its second-hand dealers in ideas literature should have been given a brief exposition (especially given Thabo Mbeki’s embarrassing “philosopher-king” embrace of Thatcherism).

The sections on Technology and Punishment are important but unremarkable. Ironically the Conclusion is very significant. It is here that Charterist mythmaking reaches “explosive” heights. The Conclusion is certainly the author's “brightest” moment of Charterism. The conceptualisation of the 1994 Civil Rights project of the ANC as the first republic is however a less sophisticated way of expressing the mythmaking of the Congress tradition. Eddy Maloka (2022) as a mature fellow traveller in the Charterist journey of mythmaking in South African politics, has called for a Second Republic in an awkwardly passionate fashion (a case of “great” Charterist minds thinking alike?). Exhibiting the naïve and embarrassing integrationist double-consciousness of the ANC since its founding moment by “civilised natives” confused by Cape liberal indoctrination, both Mpofu-Wlash and Maloka refuse to trace (white) South African republicanism to the 1852 moment: as a racist invention of the Dutch settlers who called it Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek or the South African Republic. Their fake Charterist republicanism simply refuses to acknowledge the two republics of 1852 and 1961, which preceded their myth of the 1994 first republic. Tired of radical pretensions of his shallow grasp of legal philosophy, Mpofu-Walsh “Concludes” by celebrating the Constitution. As a typical “black” liberal with radical pretensions, Mpofu-Walsh shamelessly flirts with Karl Klare’s transformative constitutionalism. This is how Mpofu-Walsh (2021:163) confesses his proud flirtations: “My argument, then, is not that the constitution should be entirely abolished, but that it should be substantially transformed. I admit, and indeed celebrate, the constitution’s achievements and advances. I believe in constitutional democracy. And I do not take for granted the constitution’s role in extending the franchise and inaugurating the rule of law”. Interestingly, Mpofu-Walsh did not have to be a black lawyer to embrace this amaRespectables’ nonsense. His Charterist fellow traveller Ngcukaitobi (a current leader of amaRespectables) accompanied him in this mythmaking journey of the Congress Tradition by stating that (2021:226), “our forefathers were in struggle so that we could have access to the law… They were fighting for the law. We cannot abandon the law.” Thus, we have here on display both radical and moderate black liberalism in jurisprudence in the form of the Azanian tradition and the Congress tradition. Mpofu-Walsh absurdly regards English as indigenous and places it on equal footing with IsiXhosa, encapsulating why he is Mpofu-Walsh. This is what happens when you intellectualise the myth of South Africa belonging to all who live in it, black and white. In conclusion, Sizwe wrote his first book to debunk 10 myths only to write another book to reinvent 2 myths of Charterism, namely the (delusional) problem of apartheid and the ANC as a liberation movement.

“Remember this; against all that destruction some remained among us unforgetful of origins…” (Armah 1973, p xv).

References

Armah, A. K. (1973). Two Thousand Seasons: London: Heinemann African Writers Series.

Carruthers, J. (1999). Intellectual Warfare. New York: Third World Press.

Dladla, N, The liberation of history and the end of South Africa: some notes towards an Azanian historiography in Africa, South, South African Journal on Human Rights, Volume 34 Number 3, 2018, p. 415 – 440.

Klare, K. Legal Culture and Transformative Constitutionalism, 14 S. Afr. J. on Hum. Rts. 146 (1998).

Lipton, M. (2007). Liberals, Marxists and Nationalist: Competing Interpretations of South African History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Mafeje, A. (1998). White liberals and black nationalists: strange bedfellows, South African Political Economic Monthly Vol 11, 13 pp 45-48.

Modiri Joel M. (2018): Conquest and constitutionalism: first thoughts on an alternative jurisprudence, South African Journal on Human Rights, DOI: 10.1080/02587203.2018.1550939.

Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2017). Democracy & Delusion: 10 MYTHS in South African Politics. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

Mpofu-Walsh, S. (2021). The New Apartheid. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

Ngcukaitobi, T. (2018). The Land Is Ours: South Africa’s First Black Lawyers and the Birth of Constitutionalism. South Africa: Penguin Random House South Africa.

Ngcukaitobi, T. (2021). Land Matters: South Africa’s Failed Land Reforms and the Road Ahead. South Africa: Penguin Random House South Africa.

Pheko, M. (2012). How Freedom Charter Betrayed The Dispossessed: The Land Question in South Africa: Benoni: Tokoloho Development Association.

Raboroko, P.N. (1960). Congress and the Africanists: (1) the Africanist case, Africa South Vol4 No3 Apr-Jun 1960 pages 24 to 32.

Ramose, M. B (2006). ‘The king as memory and symbol of African Customary Law’ in The Shade of New leaves, Governance in Traditional Authority (ed Heinz) A South African perspective. Pp 351-374.

Ramose, M. B. (2007). ‘In Memoriam: Sovereignty and the “new” South Africa.’ Griffith Law Review Vol 16. pp 310-329.

Ramose, M. B. (2018). ‘Towards a Post-conquest South Africa: beyond the constitution of 1996’. South African Journal on Human Rights. Vol, 34. Pp 326-341.

Sobukwe, R.M. (1957/2013). ‘The nature of the struggle today’ in Karis, T.G. and Gerhardt, G.M. (eds.) From protest to challenge: A Documentary History of African Politics in South Africa, 1882–1990. Volume 3: Challenge and Violence, 1953–1964. Auckland Park: Jacana.