Youssef Chebbi’s Ashkal (2022) attempts to establish a seminal psychological crime mystery film. While its philosophies and technical camerawork are strongly articulated, its subject remains underdeveloped. Where psychological dramas usually rely on the invasions, peculiarities and attitudes of its characters, Ashkal presents a very flat characterisation of its cast, leaving just the nuances of a thin storyline and some powerful camerawork to tell its whole story.

Ashkal is a visual spectacle, yet so lost in its own philosophy of meaninglessness that it struggles to fully capture its storyline.

A FLYING PREMISE

The critical issue with Ashkal is its well-established premise does not land. It remains mobile, tough to grasp. In summary, the film revolves around a pair of investigative officers, Fatma (Fatma Oussaifi) & Batal (Mohamed Grayaâ), at a local police station in Tunisia. On one part, they are tasked with solving the mystery of a murder-appeasrs-suicide by immolation, which spirals into Fatma’s more philosophical search for meaning. Meanwhile, Batal is assisting wider government agencies investigate and prosecute their police department, at the same time as a national probe into past police violence led by Fatma’s father.

So, where do these events lead us? The police probe is summarily shut down once a police officer immolates. The film struggles to make any point of this. All of Batal’s information proves moot because larger forces make their own moves, which are not clear. But, somehow, Batal’s colleagues find out about his ‘betrayal’ and set a pack of dogs against him. It is not shown if Batal survives. The culprit, who is an anonymous homme à la capuche (man in a hoodie), self-immolates in front of the police, who extinguish the flames. They are then taken into custody, but somehow escape. The culprit finally self-immolates along with a crowd of unsuspecting regular people who have followed the man-in-hood to a large pool of engulfing flames. We are finally left with Fatma staring into the flames in tears, partially of meaning.

Much of this storyline is obscure, almost as if ‘nothing happens’. The characters chase without finding. The film ends without much resolution. We are never made aware of the culprit’s motivations. In fact, they have no speech at all in the film. Traditionally, this makes the film incomplete, frustrating. We must search for some kind of denouement where there is none.

Fatma (Fatma Oussaifi) & Batal (Mohamed Grayaâ) stumble on a body.

THAT IS THE POINT

This non-finishing of the film is clearly deliberate. The uneasiness that comes with having to search for the film, complete its half-done storytelling, seems a deliberate motif for Chebbi, since the characters in the film suffer the same fate.

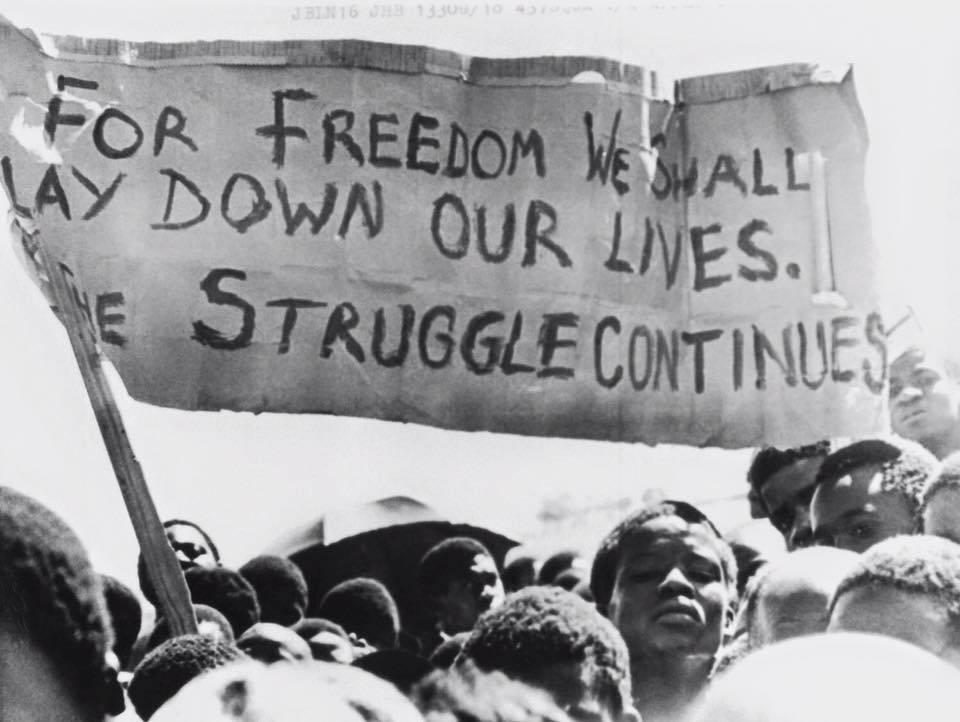

Immolation has been used historically as a tactic to create awareness about wider social issues, such as war, poverty and the loss of faith. The person who self-immolates says very little but the spectacle is the point, which causes people to introspect.

There is a Nietzschean approach to the way this story unravels, as the moral foundations of Tunisian society, its institutions, officers and public good are questioned. The catalyst is a somewhat supranatural Übermensch whose power is finally glanced by the now-believing Fatma. They cause aspects of Tunisian society to freeze, evolve, react in ways that exemplify Nietzsche’s will-to-power.

Within this will-to-power belief, we are challenged to channel our capacities, rather than suppress them. For Chebbi, they depict this as a burning, the kind of which encourages others to burn. In that sense, Chebbi completes their exploration into Nietzschean philosophy, showing perhaps that a society rife with meaninglessness will attach itself easily to some grand meaning which at once presents itself, since such a society is comprised of people without aspiration, ambition, or power. We burn through this fire because we have no fire of our own.

Fatma staring out

THE VERTICAL GAZE

Much of the film is shot from an aerial downward perspective, as the viewer ‘sees from above’ a series of immolation murder-suicides. Meanwhile, many of the characters commit their dialogue away from the camera, facing it backwards or within shadows. For their part, shadows appear prominently in the first acts of the film, mirroring the mystery of the plot. It is clear that Chebbi’s camera has its own intentions, forming themes of judgement and obscurity.

The Tunisia that we are shown are glimpses of its corners and buildings, downward shots of its fields and streets. There is a thoughtful curation in how we are shown this film which feeds into some aspects of the plot where events are manufactured by police, a commission which then investigates the police is interrupted, and the ultimate mystery of the culprit is only partially solved - we find out who causes the immolation murder-suicides but not how or why, apart from the fact that he gifts fire with his hand.

The shadows begin to dissipate into light as Fatma starts to understand what’s causing the immolations. They, after all, above all other characters are on a mission to uncover some truth. As a result, they step into enlightenment. This is hinted at early in the movie since Fatma, more than anyone else, is shown fully by the camera’s gaze. They are, in some way, the perspective-character for the film. We find out things when Fatman finds out things.

At the same time, the audience occupies an additional perspective as an active viewer of Fatma’s search, through all these aerial shots. It is almost as if we are situated in an apartment building on a top floor looking down at the city, at the police, at the culprit. This leads us into joining the film’s search.

THE POLICE ARE AN OLD AUTHORITY

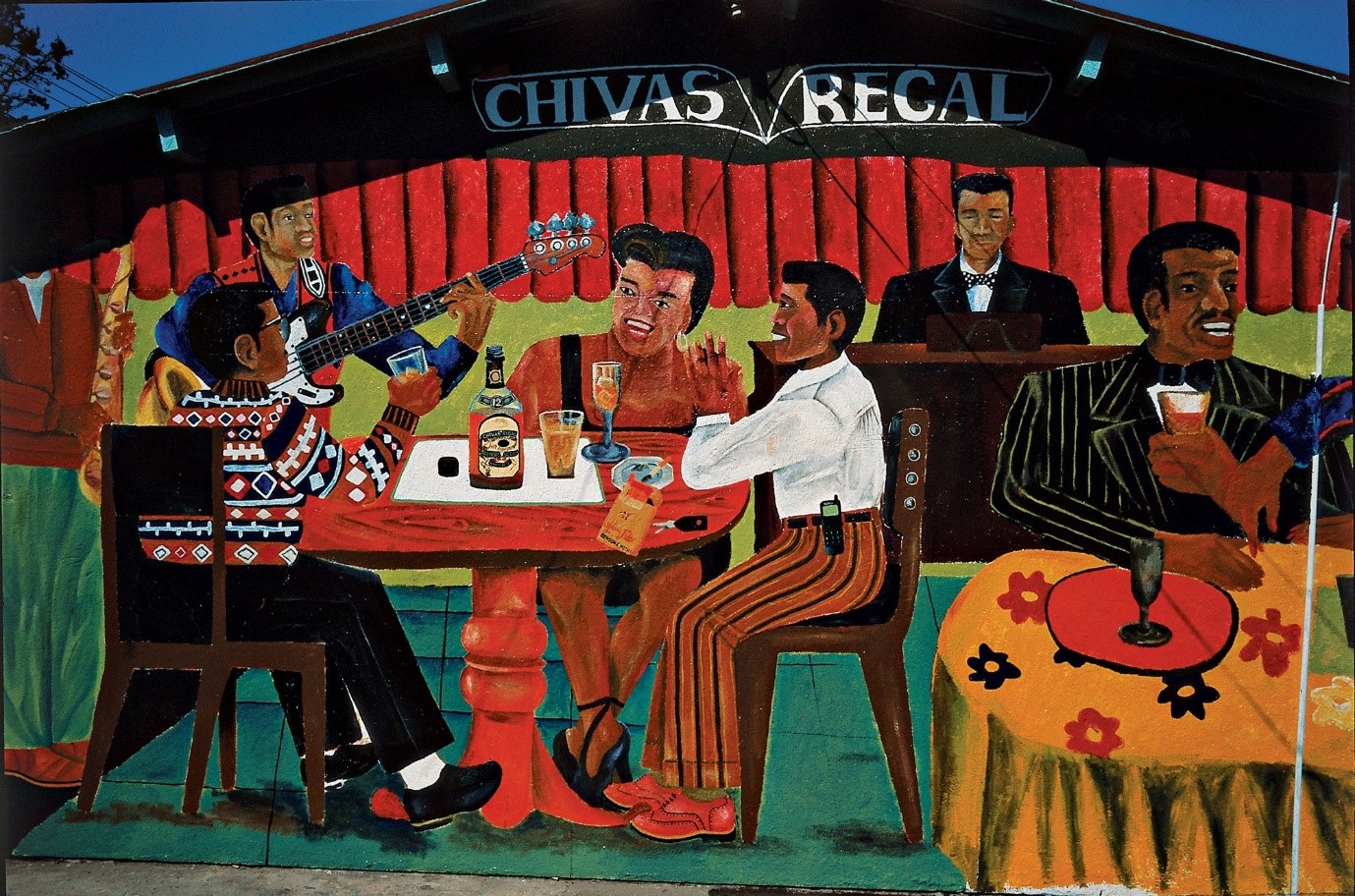

While the film leaves much of its storytelling vague and conceptual, one clear point that rings consistently is the questionable character of the police. Set within the context of the Arab uprising, we are shown how they corrupt investigations, accept money from the wealthy, commit violence against any just-doing colleagues, and act to shut down investigations into their own misdeeds.

In one scene, Fatma walks past a wall with ACAB spray-painted onto the wall. The city is clam, but secretly at unrest. Another person has immolated.