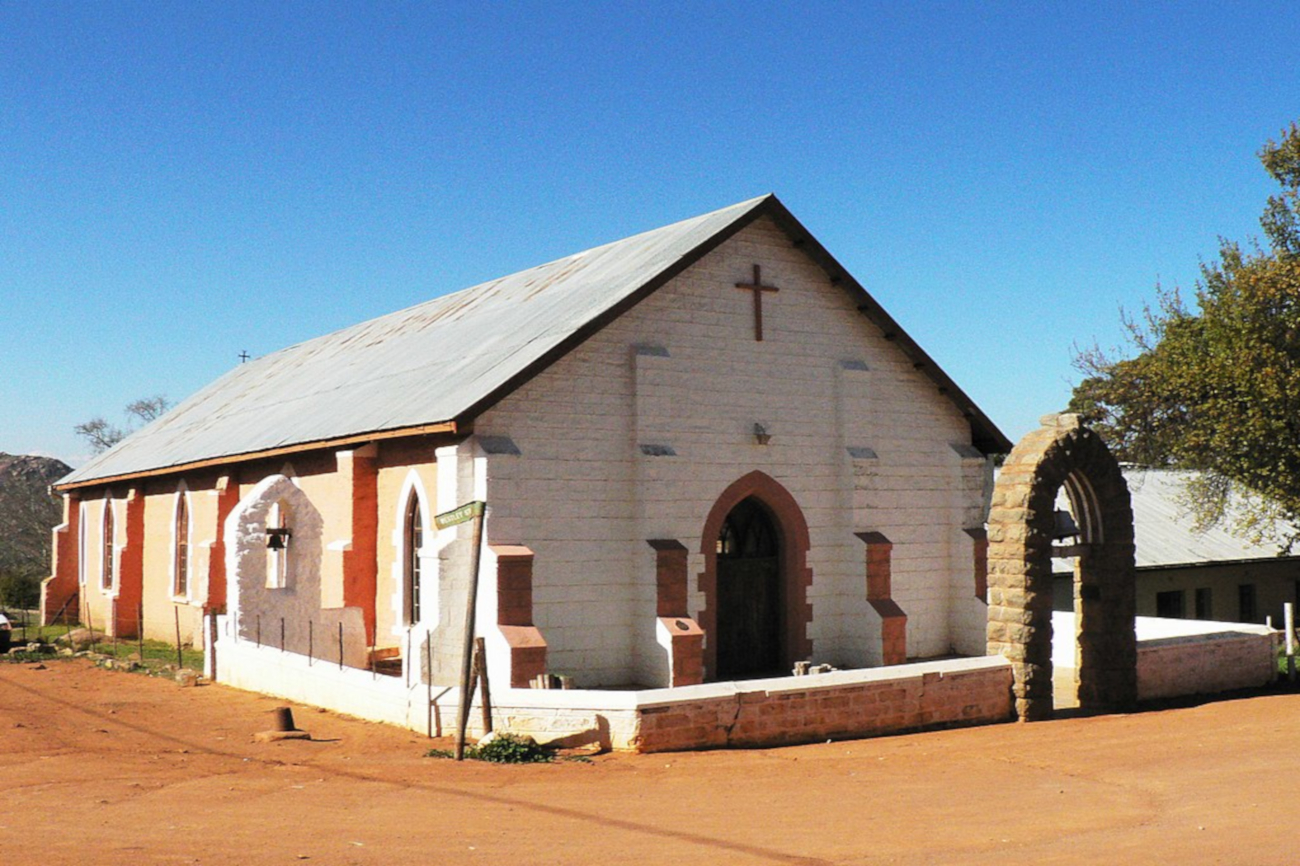

The toxic practice of religion in South Africa represents one of the legacies of set-tler colonialism, and its persistent structural problems that have seen the looting spirit and demons of the ANC leading the destruction of our moral rectitude.

The seed of this spirit is carried through toxic masculinity and the culture of ma-terialism and consumerism that have enveloped the structures of moral leadership in the country, as well as the image of the church. Thus, many of its members remain destitute while their leaders climb the ladder of wealth.

Our people turn to religion in search of solutions for their poverty and oppression. But their religious leaders see them through the cultural and economic lenses of neoliberalism.

The oppression of our people – in this era of spiritually-led development – repre-sents revenue and an untapped market for unscrupulous leaders who lead the booming Jesus Industry. These are hyenas in sheep skin who use their power and influence to abuse our people, every so often.

While this oppression maintains the growth of the individual leaders of the church, the living conditions of our people remain the same. In a way, the con-gregation has become customers who provide revenue to fund the luxurious lives of their leaders who have turned the church into a complex business entity which tends to avoid the eye of the watchdog and taxman.

This trend of taking advantage of the vulnerable characterises and exemplifies the troubles of the liberation movement. It also demonstrates how its apparatchiks see their positions of authority as the means of personal aggrandisement by turn-ing our government institutions and entities into their personal fiefdoms.

These charlatans have redefined the notion of governance and have normalised corruption, thuggery and theft, leaving our people in the hands of unscrupulous spiritualists such as Shepherd Bushiri, Alph Lukau, and Tim Omotoso.

In short, these governance failures of the ANC have created a new religious mer-cantilism entrepreneurship – also known as pastorpreneurship – under the vile of prosperity gospel that damages our communities. It also abuses the misplaced goodwill of ignorant and poor people who cannot find solace with the current po-litical order that continues to bear the architecture, framework and logic of colo-nialism-apartheid.

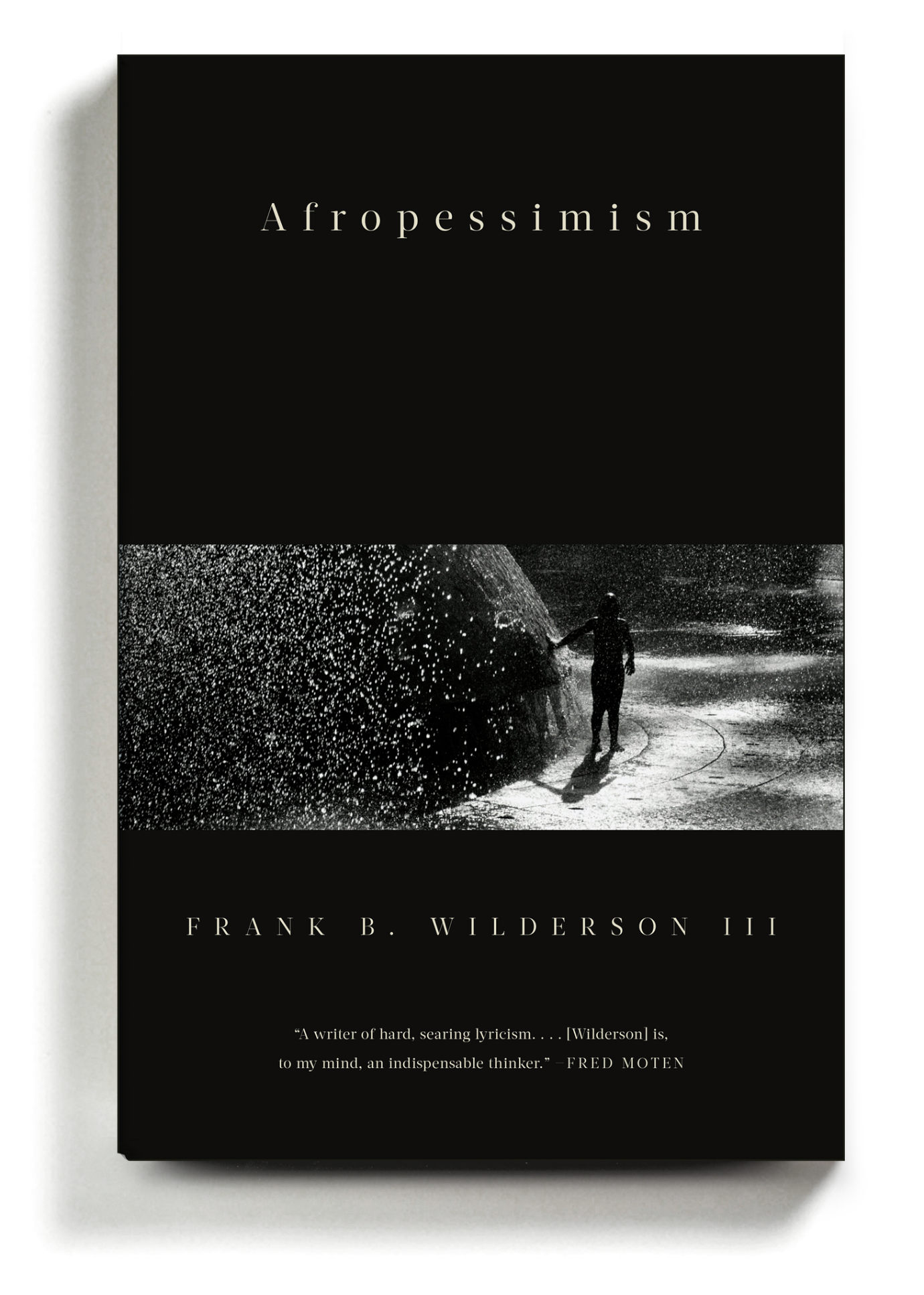

While taking its historical roots from the cultural technologies of colonialism and slavery as the proxy for social power, the intersection of government corruption and the power of these bogus spiritualists ideologically – or concomitantly – sup-ports the process of depoliticising the historical and political conditions of the suf-fering.

In particular, the discourse of prosperity gospel, which surprisingly takes its signif-icance from right-wing politics in the US and Europe, accents the concept of per-sonal responsibility of the suffering. In so doing, it undermines the culture of ac-tive citizenry and of holding politicians and corporate leaders, such as billionaires Johann Rupert, Nicky Oppenheimer and Patrice Motsepe, accountable. At another level, this discourse works through constructing the notion of self-hood which clouds some of the church members from exercising the ability to even think about how the world might be different and even collude with the structures that oppress them.

As Dr Joel Modiri, a black radical thinker, concludes, we continue to witness the rise of ‘theological and psychological discourses of responsibilisation whereby im-poverished people are encouraged to develop a positive work ethic and attitude or impelled to restore their faith in god, to name but a few forms of the control to which they are subjected.’

How does this ideologically function in South Africa? The church depoliticises so-cial and structural problems, such as poverty, through this concept of personal re-sponsibility. It shifts these problems from their political context to individual peo-ple who cannot drive structural changes in their personal capacities.

In consequence, this does not only distract the congregation from actively engag-ing in politics and civic issues but also ideologically exonerate corrupt leaders in both private and public sector from political responsibility as well as from the po-tential wrath of an angry citizenry.

On the other hand, religion remains a political tool of its own nature which does not necessarily fulfil the spiritual needs of its followers. At worse, it has been em-ployed mainly to sustain capitalist relations between the church and its congrega-tion either for ideological or financial purposes while claiming moral legitimacy because of its association with the image of God.

In the words of an American anthropologist, James Ferguson, ‘claims to moral purpose have enormous power in their ability to naturalise authority’.

Many African activists, and proponents of black liberation theology, such as James Cone, who led the emancipation of black people through intellectual and cultural traditions believe that the connection between politics and religion remains in-separable.

As a leading historian, Henrik Clarke, once noted, ‘Religion is the organization of spirituality into something that became the hand maiden of conquerors. Nearly all religions were brought to people and imposed on people by conquerors and used as the framework to control their minds.’

Although the link between government corruption and the rise of these bogus spir-itualists looks very opaque because it is not necessarily coordinated, it is not less powerful.

By virtue of struggling to correct historical injustices, as well as allowing corrup-tion to become the fulcrum of development, the ANC government has created a favourable environment for the growth of corrupt spiritualists who prey on the vulnerability of the suffering who also face exploitation at the hands of white-owned companies.

Although the image of God – and its abuse – take the centre stage in this power dynamic, this remains a political question. It pushes political responsibility into the hands of the ANC which has betrayed the struggle for the economic emancipa-tion of our African people, especially women, who bear the large scars of its tyr-anny.

Culturally, these rapidly escalating moral decadence remains a damning indict-ment of the party’s lack of leadership in our society, especially its failure to con-struct a new cultural identity to unite different tribes and races in South Africa.

The appalling stories of Bushiri and Omotoso interrupt the dominant assumption that South Africa made a radical rupture with its colonial past by highlighting the continuing patterns of religious indoctrination which facilitated the destruction of African spirituality and cultures.

As Clarke decried, ‘Our church was an imitation of the White church. All we did is to modify the old trap. We didn't change the images, we became more comforta-ble within the trap. We didn't change the images, we changed some of the con-cepts of the images, but the images remained the same. So, the mis-education that gave us a slave mentality had been altered. But it remained basically the same.’

Metji Makgoba is a Commonwealth Scholar at Cardiff University and writes in his ideological capacity.