The Vavasati Festival (hereinafter, Vavasati) runs throughout the month of August at the State Theatre in Pretoria. With this year being its seventh in the same venue, Vavasati will showcase a broad spectrum of established artists, and little-known works by new and mid-career artists from South Africa, Namibia, and Germany. Multi-award-winner and 2011 Standard Bank dance artist of the year, Mamela Nyamza, and theatre practitioner Kgaogelo Tshabalala are curating together a miscellany of disciplines at this year’s rendition including theatre, poetry, musical theatre, dance, performance art, music, and visual art. As a festival on South Africa’s cultural landscape, the contents of the Vavasati program make broad statements about scarcity and capacity building with the inclusion of workshops on arts administration, writing, and directing. Being one of only two large-scale festivals in the country that present works only by women, Vavasati also makes strong statements on representation.

Some of the issues Vavasati highlights are the power dynamics involved in debates about representation. For instance, there’s currently a movement in the world of jazz for the representation of women musicians beyond vocalists. This movement advocates for 50% representativity of women on event line-ups. The movement is especially felt by jazz festival administrators since festivals are prominent on live music schedules, and musicians compete to be on festival line-ups.

At this moment in history, it is therefore no coincidence that there are more all-women big bands, more female-led bands, and generally line-ups that signify this desired gender inclusivity at jazz festivals. Such a movement has not only been driven by logistics, but is a sign of political climes, and broader conversations about social justice and cultural management. More importantly, this movement represents just one of the terms through which women are often discussed in the cultural sector, as a cause or a conundrum. Not as normal or equal participants with agency in the cultural sector, but as a baffling group of people whose agency is still being negotiated even though they, like men have always been co-creators of cultural value.

Another conversation linked to representation is one that has been going on within the creative community as well as in academic and political circles in South Africa since around 1994; it is a conversation around whose responsibility it is to develop culture and why. Sometimes this conversation veers towards the role of state entities, including universities (since they are publicly funded), in holistically developing the cultural sector and all its participants equally. Most universities, for example don’t include arts administration in their arts education curricula, and most universities do not consciously try to manage gender representation in arts programs. As much as the conversation on whose responsibility it is to develop culture happens, pressure still falls on local and often private festivals to take on the responsibility of equal representation, artistic development, education, etc. Other institutions basically transfer this responsibility, since they cannot fully undertake it at the moment, to festivals and similar initiatives.

Consequently, festivals do more than just stage a series of concerts. They also take on responsibilities such as showcasing new talent from various, often marginalised, communities and provide skills development workshops. They have found the benefit of this from the realization that padding the artistic line up with workshops means that they can expand their attendance numbers. With larger audience comes an opportunity to motivate for more sponsorship, and with more diverse audiences, is an opportunity to diversify funding sources for the festival.

It is therefore not uncommon to find supplementary skills-building workshops for arts writing or arts management on local festival programmes. These are skills that are scarce in South Africa, and such padding to the artistic content thus addresses regional or national capacity building. If they are not being developed at universities, other institutions of higher learning, or at cultural organizations funded by the state, then festivals are where such skills are developed.

This is where Vavasati comes in; it addresses skills shortages with its programme and by virtue of being in the accessible Pretoria city centre reaching a demographically diverse audience. The development happens as a result of the space showcasing and exposing talent not only to the audience, but gives it room for mobility through the multi-sector networks at the festival. Vavasati also develops culture by showcasing works by creators of different socio-economic backgrounds.

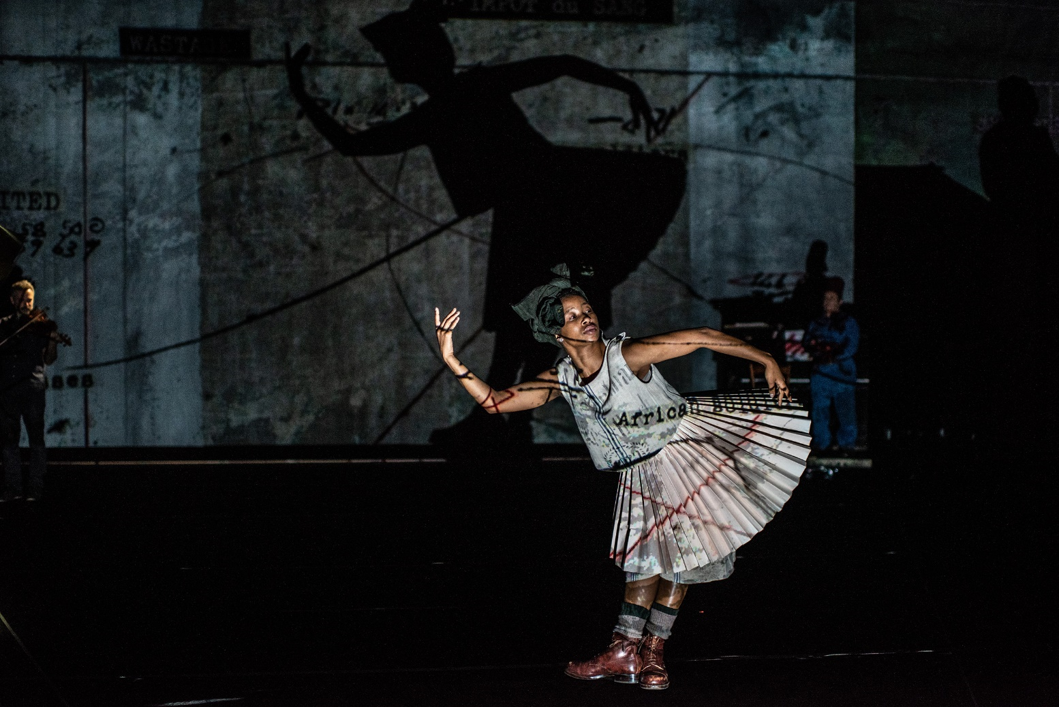

The female focus of Vavasati provides a needed platform for women who are often ignored and made invisible as producers, performers, creators and administrators of cultural knowledge and value. This is another form of cultural development. It confronts the imbalance in performance and other cultural spaces that are still male-dominated. Yet even though the festival happens in the month of August, a single month dedicated to reflection on where South African women are situated in our society, it is not viewed by its curators, who also happen to be women, as a tool to bestow power upon women. Instead, women at Vavasti are presented as already having power.

The curators suggest that the festival’s slogan, “Inequality!!! Seizing the Megaphone”, means that the festival is not a negotiated charitable platform for women. The slogan is about an exertion of power. Women are seizing the megaphone as legitimate producers of cultural knowledge and value. They are not presented as objects or subjects but present themselves and tell their own stories. The curators perceive the festival not as an extraordinary space, but a regular space of cultural production with a particular theme: vavasati, meaning, “women”. A theme that means multi-generational women are presented at a state-owned cultural institution, where they also belong. As a result, the Vavasati festival comes slap-bang in the middle of the politics of scarcity, capacity building and representation. It does not style itself as a unique occurrence. It makes a statement about normalcy, where women are normal everyday cultural producers.

*Dr Akhona Ndzuta, is a researcher who focuses on the intersection of South African music, public policy and cultural management. She is a member of the Vavasati Initiative.