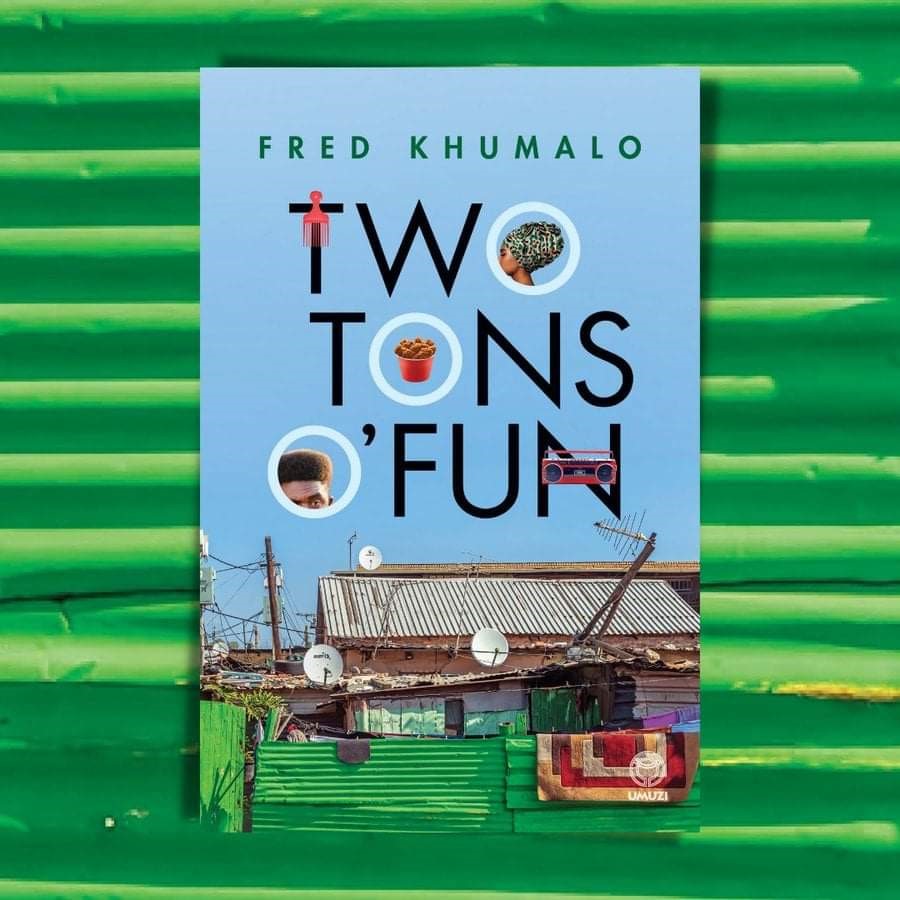

Breathless! This is how I felt after being spat out of the afternoon hustle and bustle of Johannesburg's pavements. Bridge Books on Commissioner Street was my destination, to attend Fred Khumalo’s book launch. Who needs Uber navigations when the smell of books draws you in like Gogo’s khaki cabbage meals through the chaotic city landscapes? Owls, bloodshed, gossip, witchcraft, cheap deodorant and street fights along with plot twists that took hold of my soul’s throat. Oh man, Two Tons O’ Fun left me breathless but at the same time hopeful. “A celebration of friends and family” was Khumalo’s response to a question by an audience member about the contents of the book. Indeed, this latest offering is a literary festival of township culture, sisterhood and community relations; driven by unyielding yet hilarious characters that live life unapologetically. Set in Alexander, a vibrant township north of Johannesburg, this easy read paints bitter-sweet images of a disadvantaged people seeking better economic and ontological pathways. Not only battling internal ghosts, but also past traumas that haunt the rat-infested streets of what many Black disadvantaged communities call home.

Black female voice

Two Tons O’ Fun has a very strong cast of female characters. I pose a question to Khumalo with regard to how he was able to invoke a female voice as a male writer. He admits that character development with a female voice is always a challenge but finds that “women are great conversationalists” so, as a writer, paying close attention and listening with care is essential. The novel is narrated by Lerato Morolong, a tall and chunky teenager navigating life’s complexities for the first time, this book is a journey of her rite of passage; filled with laughter and lessons. Armed with a unique brand of English termed Zunglish, Lerato is curious, adaptable and bold in dealing with issues such as body-shaming, sexual identity, inequalities and belonging. She lives with her mother June-Rose and two siblings - older sister Florence and younger brother Tshekiso. Lerato’s family, the Morolongs, stay in a compound that they share with five other families. June-Rose is a strong-willed character with survival strategies for beating poverty; through theft, prostitution and alcoholism. Her character, along with the other Black female characters found in the book, is a representation of a certain type of Black woman from disadvantaged communities in South African townships; battling with generational traumas but finding ways to live fiercely.

Paradoxical existence

One of the prevailing themes in this novel is a paradoxical existence that many readers may relate and some may find new insights. The contestation between religions vs. African spirituality; privilege vs. poverty; patriarchy vs. women empowerment cuts across the entire book like an Okapi through a fresh apple. Despite such contradictions, the author illustrates a beautiful co-existence of pain and joy, a cross-cultural experience of lower and upper-class dynamics, along with newly formed unlikely sisterhood and friendships. Essentially the book delivers an orientation on Alexandra’s political, ecological and art history to readers not exposed to such knowledge, thus serving as a reflection on the overall South African township experience.

Class analysis and relations

Another significant theme explored in this book is class dynamics and relations. People can be living in the same township, and yet some live in isolation and privilege, while others live loud, proud but hungry and poor. This is the case with the highly educated Gugu Ngobese and her English-speaking daughter, Janine. These characters offer readers an understanding that not everyone in the township is living the same experience, although coming from the same kind of area. Often referred to as “those white people”, the Ngobeses also serve to interrogate the idea of “Black Privilege” … a phenomenon that may often lead to guilt and overcompensation by those in better economic positions. Talking about her mother, Janine observes at one point that, “She feels guilty for being more successful than other black people. She goes to ridiculous lengths to help those less fortunate than her.”

These inequalities and class differences can create a hostile living environment between families, particularly in township settings. Some community members walk chest-out, qualified with PhD (Pull Him Down) degrees; with words of envy and resentment rolling off their tongues. “They eat you jealous” is the catchphrase when others throw words like half-bricks at those achieving their goals. “Deriving pleasure from other people’s misery. It kept us alive, knowing that the next person was more miserable than us. Made us feel better about ourselves,” says the narrator. Such inequalities have a debilitating effect on the human spirit, where feelings of worthlessness, shame and anger fester sub-consciously. This leads to issues of domestic abuse, where some disempowered men even use patriarchal religious subtleties to justify feeding wives and children sjamboks and fists for supper, and some parents beat their children for the most frivolous of reasons. All these toxic behaviours seem to be skewed ways of regaining their power and dignity.

Reading in townships

The book also explores the lace k of reading culture, and myths around books in the townships among both young and old. “In the ‘hood, it was believed that if you read too many books, you simply went bonkers,” narrates Lerato as she experiences a study filled with books for the first time. The learning journey Lerato goes through affirms the importance of mentors and aunties as much-needed supported structures towards accessing educational opportunities. Reading was a catalyst to opening up a new world of discovery in my own life, in my teens, with my mother handing me the likes of Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions (1988). My mentors prompted me to read heavyweight African Writers Series writers like Bessie Head and Chinua Achebe. I could relate to Lerato’s “Vocab Book”, which in my case was a treasured hardcover that held all-new English words I heard from the TV soapie Isidingo, Hip Hop songs or books read at school. My mother’s battered black-cover Oxford Dictionary was my chief resource before Google’s search engine drove my research process. Reading Two Tons O’ Fun, I had flashbacks of the embarrassment from the disapproving stares of passengers as I read a book in a crowded taxi.

Target audience

Some readers might however find this latest release a light read, compared to other novels by this veteran author, such as The Longest March (2019), Dancing the Death Drill (2017) and Seven Steps to Heaven (2007). Another question that burned in my mind as I sat in the book-launch audience was, who is Two Tons O’ Fun written for, exactly? “Target market can be stifling to the creative process,” responded Khumalo. Although he says he hardly thinks about the target audience, in this case, the author did think about it for the most part. “You don’t find any F-Words throughout this book,” notes the author. Khumalo does confirm my initial thoughts on the book, which are that, ideally, it could be recommended to Primary and High School learners across the spectrum of our diverse nation. Such a book may galvanise much-needed conversations between the different lived experiences of our teenagers, to better understand each other’s contexts, and to encourage social cohesion and empathy.

Conclusion

Two Tons O’ Fun offers a teachable moment for those disillusioned by the “better life for all” rhetoric in government speeches and policies. As we seek a better life for our children in gated communities, this book offers a window into a daily reality most South African’s still live in. It opens up an awareness of the contest between two worlds. It is a call to the broader society to appreciate that those in townships are human beings as deserving of respect and dignity as anyone else. “People in Alexandra lived. Really lived. When you are hungry and desperate you embrace life fiercely. You cannot take it for granted,” narrates Lerato.

Two tons of fun, tears and tragedy, yet approached in a witty and sensitive way; this book is about resilience and hope. As I ordered my Uber while autographs and pictures were being taken, I took my last few breaths of the enchanting smell of books in the store. Tons of hope filled my heart about how the future will turn out, and how this latest release from a prolific writer seeks to bridge different experiences among South Africans.