There’s A Meth-Head On My Veranda

The township of Kwa-Magxaki in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (Port Elizabeth, PE), capital of the Eastern Cape in South Africa, has a history rooted in the emergence of the Black middle class. At the height of apartheid in the 1980s, the suburb was built and featured houses that echoed the aspirations of the up-and-coming class; hot running water, big windows, spacious stoeps (verandas), and indoor bathrooms. The houses catered for a nuclear family; 3 bedrooms, kitchen, living room and dining room. Naturally, some houses were bigger than others, depending on the family's means. Teachers, doctors, lawyers, pastors, engineers and other professionals moved their families to this suburban township. Some clerical workers and administrators, who were likely single moms, pushed beyond their means and got themselves houses in the neighbourhood and its sister township, KwaDwesi. My late aunt was one of these women, and my cousins continue to live in her house. At one point, my mother and another aunt co-owned a house in the neighbourhood. I have a lot of memories in this township. Many of my firsts happened there, and I formed habits and patterns in that hood. Democracy in 1994 came with renewed hope for the next generation. Millennial Black children began attending better schools than those their parents had been offered through Bantu education. As time will always tell, each generation has its vices. Every other family was gripped by alcoholism in the 1990s and early 2000s, and the 2000s and 2010s ushered in a narcotic subculture largely influenced by the nightlife in PE central.

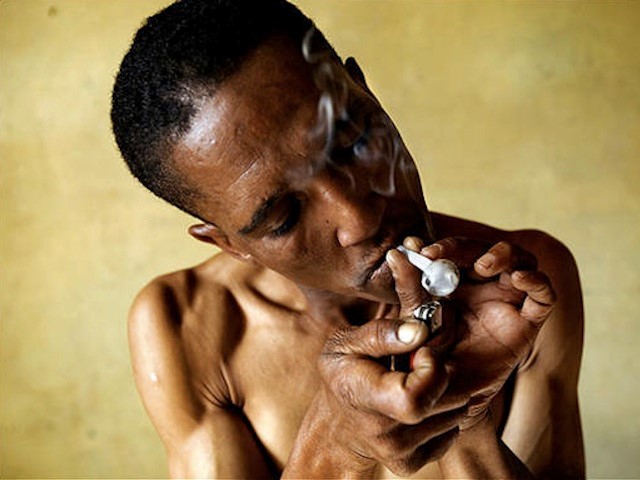

On any seemingly ordinary Saturday, Sunday or perhaps Monday, Lwazi might be pacing up and down his childhood bedroom. His mother died last year, and he lives with his older sister and her children, who are in university. Lwazi talks to himself non-stop, he sits with a persistent erection he can't control and watches copious amounts of porn. On Tumblr, he indulges in videos of girls smoking meth and blowing meth clouds into the camera. He might make some art if any coherence emerges from his high. He is high on methamphetamine. Also known as tik.

“I have always been curious about drugs. Being told not to do them is exactly what made me do them. Plus, I really loved TV, and TV culture influenced a lot of my decision-making as a kid.'” He tells me when I ask why he uses tik:

The drug has been largely associated with the coloured community, whereas Mandrax, Woonga and Nyoape are often associated with Black communities. The highly addictive nature of a drug like methamphetamine devastatingly affects poor and working-class communities. In recent years, the use of methamphetamine among youth in historically Black townships across the country has increased steadily. Gang culture has hugely impacted the infiltration of drugs among young people, who join gangs from as early as 9 years old. Youth idleness, high unemployment rates, the repercussions of HIV/AIDS, absent parenting and addiction continue to hinder economic and social progress. Still, few people would think these same problems plague the rolling hills and urbanized landscape of Kwa-Magxaki.

Born in 1985, Lwazi's mother sent him to a multiracial school in a different part of town, and he commuted to school every day.

“Honestly, I wanted to go to Kwa-Magxaki High!' Lwazi tells me, referring to the school I matriculated from.

Kwa-Magxaki High School offered quite a mediocre education according to us, the kids who went there. The kids who wore fancy blazers and spoke with a twang like Lwazi had it better than us, we felt. However, Lwazi feels that education is the same no matter where you go. He was the first in his family to matriculate. It is at this high school in the suburbs where he would discover the kind of music us ghetto kids were not accustomed to. Grime. Dub Step. Trip Hop. Trance. The music encompassed an alternative culture, and because he’d grown up a black sheep in the neighbourhood, he gravitated towards subcultures.

This country currently sits at a 29% unemployment rate, and the Eastern Cape is home to the highest unemployment rate at 46%. Not many of the descendants of nurses, doctors and teachers of Kwa-Magxaki took up these same professions, and often life after the twelfth grade is nearly hopeless for many of my peers. Some of us relocate (like I did), and others pursue further education and/or get jobs. The stress and pressure of being unemployed can take its toll on a young creative in a small town like PE; it took Lwazi seven years to finally land a job. As diverse as our life paths have been, my peers and I have faced substance abuse head-on. We have struggled with smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol and experimented with different drugs. Others get hooked, while others dabble and use them recreationally. Lwazi falls into the latter category.

This country currently sits at a 29% unemployment rate, and the Eastern Cape is home to the highest unemployment rate at 46%. Not many of the descendants of nurses, doctors and teachers of Kwa-Magxaki took up these same professions, and often life after the twelfth grade is nearly hopeless for many of my peers. Some of us relocate (like I did), and others pursue further education and/or get jobs. The stress and pressure of being unemployed can take its toll on a young creative in a small town like PE; it took Lwazi seven years to finally land a job. As diverse as our life paths have been, my peers and I have faced substance abuse head-on. We have struggled with smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol and experimented with different drugs. Others get hooked, while others dabble and use them recreationally. Lwazi falls into the latter category.

Tik is growing in popularity in Port Elizabeth and not even the spread of COVID-19 is slowing down its supply; Lwazi continues to get a steady supply from his dealer. Port Elizabeth trails Cape Town in the use of the substance. At the time of writing this story, Lwazi and I have been chatting telephonically for two months and built a bond. His claim of smoking only once every other month is a bit shaky as we build a rapport. His memory seems to fail him at crucial points in our conversations, and he reveals to me that he no longer has front teeth. These are the very mental and physical implications associated with methamphetamine; I ask if he would consider quitting.

“Eventually, I will quit meth because physically it's damaging,” he says. “When I can start growing 'shrooms or find myself a proper plug [for mushrooms] I will gradually stop. I also do LSD when I do not feel like meth, kinda the same high.”

However, this is also a question of affordability for the father of one. Should Lwazi decide to quit, his biggest impediment would be finding a rehab facility to free him of the substance. As a country, South Africa is lacking in government-funded support for addicts. Rehab facilities are often operated by private entities and individuals, a cost Lwazi could not afford, at ZAR75 per cleaned wagon he earns. Facilities usually operate independently, and there are few and far between rehab centres that cater to the poor. Quitting methamphetamine on your own is nearly impossible. Cultural activist, Rushay Booysen, saw this first hand as they tried to assist one of his cousins, who was hooked on tik, by housing him. Their efforts failed and his cousin eventually had to move out, and he continues to use the drug.

A few international meth communities have mushroomed on social media in the past few years, with a local prominent one catching my attention; but it stopped being active two years ago. Despite the inactivity, the page caught my attention due to the high level of interactions, comments from young users in the Eastern Cape who wished to quit, and an evident spike in young women taking a liking to the drug. One female user comments on a post that it helps her clean her home from top to bottom, keeps her libido up, and keeps off unwanted weight.

Enter politics and government involvement in social ills. The lack of free rehabilitation programmes is alarming and even in private facilities, the recovery rate is low due to having to integrate back into society, where your very circumstances threaten your sobriety. It’s not clear whether Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings are available in PE townships, but I wonder if Lwazi sees himself as needing to attend NA meetings; because he regards himself as a recreational user. A clear lack of rehabilitation services was highlighted in 2016, when the Department of Social Development opened the Ernest Malgas Rehab Centre for children. This caused an uproar in the community, who claimed it was biased because the older generation was being excluded. Citizens also saw this as another front for embezzling money from taxpayers and demanded answers regarding the lack of jobs in the municipality. Edmund van Vuuren, MPL DA Shadow MEC for Social Development, penned an open letter questioning the current state of the Ernest Malgas Rehabilitation Centre, and the bizarre decision to close the doors of the only facility offering free rehabilitation services to addicts. The closed facility was operated by a national NGO known as South Africa National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (SANCA). Port Elizabeth is one of the most officially corrupt cities, and Crispian Olver paints a picture of the extent of the corruption in his book, How to Steal a City – The battle for Nelson Mandela Bay: An Inside Account, published in 2017. The element of corruption causes chaos at the bottom of the scale. Despite those who 'try'; it is difficult to escape the tentacles of the corruption machine.

Social workers have played an important role in solving social ills on the ground. Methamphetamine and other drugs, including alcohol are wreaking their havoc in families. The rise of the use of the drug results in reckless gang culture and violence. Homes that have been dismantled by oppression, HIV/AIDS, gangsterism and economic inequality struggle with their addict sons or daughters. Many family members are living in fear of a raging addict who might do anything to get high, and some families resort to locking valuables away including groceries. Before a social worker swoops in to save a family from its demise, a boy as young as 9 years old may already have had interaction with a gang and/or abuse (substance, emotional, sexual, physical). It’s difficult to give an exact figure on the impact on individual families, but as I speak to family and friends about this issue, they each have a story of how this drug has affected them on one level or another, and this includes my own family.

In the first week of June, I notice that I barely hear from Lwazi. I text him, to check-in. Communication is scant; he responds in tidbits. This is familiar; he just got paid. I am certain he is getting high. These motions are familiar; at the height of my alcoholism, I’d disappear down a bottle as soon as I landed some cash. The moment I drank, my anxieties went away and I felt less 'needy' and pushed many people away or kept them at bay. I have to draw my boundaries with Lwazi, but I have a bad feeling. I even have a disturbing dream. The morning after my dream I find a message from him:

“Sorry for being distant and silent. I had a bad experience on Sunday night. Sleepwalking/psychotic episode/paralysis. But it happened and apparently, I was seeing shit that wasn't there. When I recall the events, they all seem like a dream, I believe the meth is taking its toll. Plus I believe it was more than the meth tho. I have a lot of anger n pain which I need to define and deal with. Hence I do art, I think.”

My moment of clarity arrived during a similar substance-induced psychosis; for a few days, I lit a white candle to neutralise the energy around me and burned lots of incense. I advise him to do the same. I hope the candle also helps his family recover from collective trauma experienced during the psychosis. They’re already suspicious that he’s on something other than weed, and this probably confirmed their suspicions. I also tell him what I wish I was told when I felt overwhelmed by guilt and shame because those around me had finally found out that I had an actual drinking problem beyond 'having a bit of fun'.

“You are loved. You are deserving of kindness. You are cared for. Your mother’s love surrounds you, bask in that. Peace be.”

*Not his real name