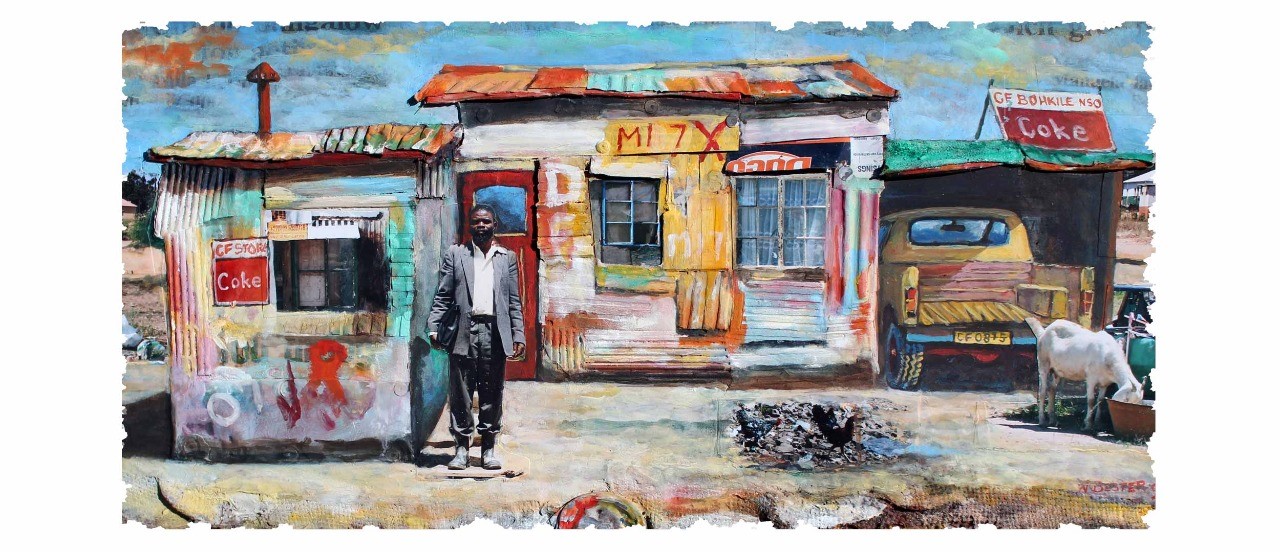

Vivien Kohler’s solo show at Gallery MOMO in Johannesburg feels like a debut for an otherwise seasoned artist who, in my estimation, is one of South Africa’s finest portraitists. Why a debut?

Because after years of lockdown, and resultant introspection, the artworld now realises that solo shows can no longer be business as usual. Isolation, introspection, the utter defamiliarisation of normative systems of conduct and belief, as well as a re-evaluation of taste, has forced us to rethink what art means, what it does. In Kohler’s case, it has forced him to review his faith.

Since 2020, we have seen an accelerated interest in black portraiture. The momentum was growing prior to Covid, but there is surely a connection between enforced isolation and the emergent culture of revisionism – in which the economy and culture of the artworld, and its collusion with systemic inequality, has resulted in a critical and long overdue re-evaluation of values. Staffing is being radically overhauled, diversity instituted. As for manifest content, what do we look at and value? It is an incontrovertible fact that the defining optic is blackness – black artists, black narratives, bodies, lives.

In the case of Kohler, a black South African artist – who prefers to see himself as a post-Imperial racial and cultural hybrid – the matter was never about the fetishization or monetisation of black experience, but its complex psychic drives and yearnings, which are as transfiguring as they are bonded, or entrapped. It is this paradox – of power and powerlessness – which defines the mood of his paintings. They are never one-dimensional, never prescriptive.

Two paintings, recently dispatched to Portugal, are tellingly titled ‘Rapture’. An intense feeling of joy and, according to millenarian belief, the transporting of believers into heaven, the rapture is as wildly surreal as it is profoundly felt. What it does trigger, however, is the realisation that Kohler does not see the human condition as bound by reason, as terrestrial, but as one that can detach itself from any controlling mainframe, and, literally, transfigure itself.

This drive, akin to extasis, a delirium or outer-body experience, firmly positions Kohler’s paintings at a threshold between this world and the next, an inherited history with its received limits and conditions, and an ahistorical, unbounded, and boundless realm beyond.

The title of Kohler’s solo show – This too shall come to pass – evokes this will towards transfiguration. His bodies are resurrected, their physiognomy balletic. One gasps in their airborne midst. Rapture… ecstasy … trance … amazement … form a lexicon of feelings and drives one typically associates with religion, principally religious iconography.

There is no doubt that this is the case, but to simplistically regard Kohler as a ‘Christian artist’ is to miss the mark, for what impels him is a state of faith and grace in the purest and most inclusive sense. Irrespective of personal belief, Kohler’s paintings touch one, because they speak to our deepest and most profound yearnings.

In an age fatigued by Reason, driven by hysterical conflict and division, the utter collapse of neo-liberal democracy, it is unsurprising that we find the resurgence of an oppressive and exclusionary identity politics – Us versus Them. It is against racial and ethnic hatred, against the pitiful narrowness of nationalism, that Kohler returns us to a greater, more tender state of grace. This is his greatest contribution to a local and global artworld.

Kohler sends me another possible title for the show – Hung be the Heavens with Black – and I realise that the rapture he envisions is one in which the oppressed and segregated against enter a triumphal afterlife.

While most contemporary Black African artists celebrate their newfound and newly minted currency, Kohler signals the divinity within the oppressed body. While others concretise and manipulate black identity, Kohler champions its ‘relationality’ – its greater human and divine connectedness. His art is driven by dreams, he says, dreams which he sees, feels, but never quite understands. Instead, it is the mystery of the dream structure, and its inscrutable content, that impels him.

Unlike the psychoanalysts Carl Jung or Jacques Lacan, Vivien Kohler is not interested in finding a defining structure for the unconscious. He is no symbolist. Rather, after Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109), Kohler holds fast to the dictum

– Credo ut Intellegam, ‘I believe so that I can understand’. In other words, it is belief which drives the artist’s vision, and not an ideological, political, or theological dogma.

Frankly, Kohler’s approach is refreshing and heartening. For my part, as a secularist, I concur with Alain de Botton who notes that ’The error of modern atheism has been to overlook how many aspects of the faiths remain relevant even after their central tenets have been dismissed’. Much remains profound within faith systems. Contra the cynical view that art is ‘a religion for atheists’, I believe that it is a profound source of hope, regeneration, and transfiguration. In this regard, Vivien Kohler has emerged as our guide before a divine threshold.

*For more information on the exhibition please visit

![1976 [Part2]](assets/images/1976.jpg)