Sick songs of silence, healers brew just to keep thorns at a distance. Transmogrifying the now, sentence by sentence, vinyl after vinyl, image over image. Tracing the unwritten, unheard and unseen pasts to forge a tomorrow radically different from the present. These pasts live in us, in the marrow of our bones. Sometimes we remember them sometimes we don’t, but they are always there like the dark shades on the crescent moon. Drifting with Muntu Vilakazi. He thinks a lot and speaks a lot, at times drinks a lot. And, he never really got over the habit. Of telling people shit in jazz sessions and exhibitions. Straight talk no banter. Like, ‘your consciousness is rented’, ‘just play the drums man’ or his favourite line that he always says with swing ‘do these cats really know what this shit means?’ But that is not the point, the point is the archive. The archive not just as a repository with vestiges of the past that we can always a consult to understand and construct reality. I am interested in the silences, in the exploration of our experiences that refuse to be archived in certain ways. Testing the limits of what can really be archived, that intangibility about us ‘that bends Blackness itself’. 1

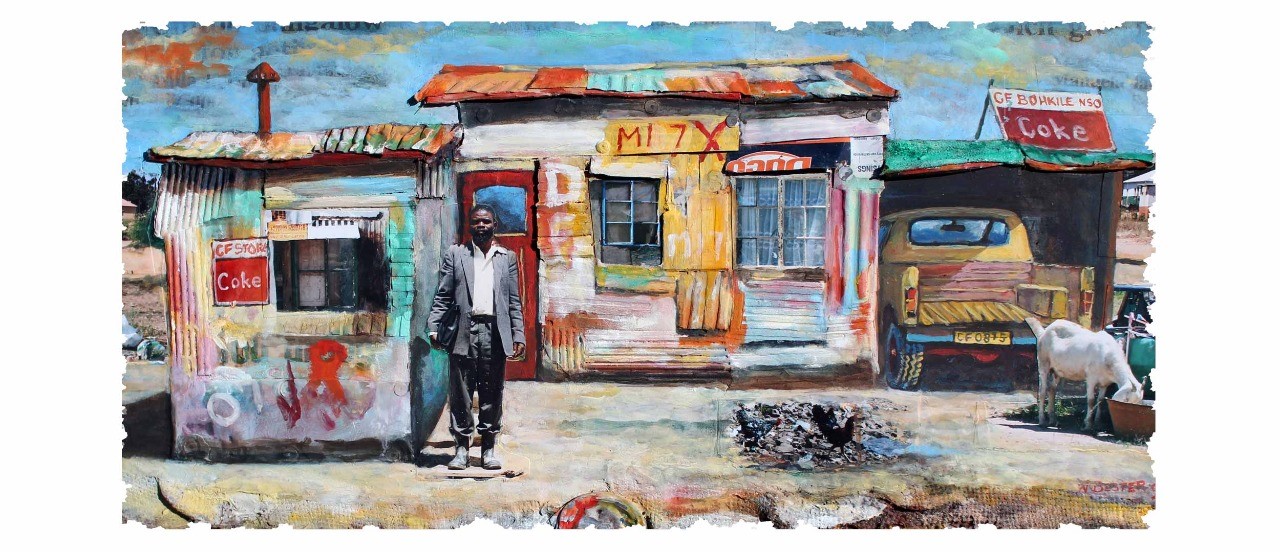

Down Kenmere Street, Yoeville. Saturday morning a night after Lesego Rampolokeng’s (non)-performance. Paintings, records and books scattered all over the house. We listen, from Mahlathini to Johnny Dyani to a Chris Hani speech, a mash of chants and amagwijo. Muntu Vilakazi’s collection of records is great, not just in quantity but also in the variety of names that appear. This is a sign of his discontentment with categories and the boundaries that they enforce which often stunt ‘aesthetic mobility’. So we play jazz, blues, maskandi, umgqashiyo but within these genres there is an overlap which in some ways resonates throughout the music. I wonder how long it has taken him to collect but I do not ask, by now I know that I might not get the answer. On the wall there are a couple of quotes written in charcoal, a Vusi Beauchamp painting and a framed certificate of the Thami Mnyele Fine Art Award he won in 2017. He is always reluctant to speak about his photography work, every artist’s anxiety. But I have seen it, glimpses of it. His images are a critical commentary on Black youth culture and the church as an important aspect of Black life. They are a close look at the ‘quotidian’ and the mundane of city/township life as an anecdote we can use to think about our condition. His work bears witness to the fact that the politics are always happening and that we are always engaged in resistance (the beauty and the ugly of it).

"

"

Vilakazi’s work becomes important because when we speak of the archive we are not only interested in the works of the dead, of those who lived before us. Of course we have to pay homage to those who have contributed in both formal and informal ways because without them we would not be able to oscillate from the past to the present. But this does not mean that we have to keep the archive pristine. We consult it, challenge it and retrieve whatever we need to respond to some of the questions we are grappling with. More persuasive then is the idea of a ‘living archive’ which entails an always happening and never completed project. This is what Muntu’s project has been about, the documenting of the present as a response and a conversation with the past. This can be seen in his 2014 series titled Politics of Bling which in interesting ways questions the idea of success and beneath that critiques the ways in which we imagine freedom as Blacks in South Africa. These questions remain relevant making the series a body of work that we might still need to look at closely. Of course there are always two possible stories when we think about narratives that collections and assemblages of things we make. One is the story of what the narrator (artist) thinks he/she is saying and that which the audience understands and imagines. So Muntu could have very well thought that he was doing something else but we interpret the work as something else and that is the beauty of the archive, it can be read differently depending on the concerns of the day.

At the core is therefore an invitation to think seriously about how we engage the archive. Both the public archive which is available in museums, galleries and libraries and the private archive which is an archive that is built oddly by individuals over the years. What dialogic possibilities exist and how can we create new ways of engagement. This is to say which questions can our present put to the past to find suggestions for better tomorrows. Of course we must always bear in mind that archives always exist within a certain cultural power and authority and it is precisely because of this that we must open room for questioning and contestation. This will in turn assist us in uncovering all the layers of meaning in our past and present experience, meanings that are silenced by those who do not want to see any change in the status quo. We know them, those who insist in the depiction of Black people as devoid of culture, intelligence and soul. Those who have been engaged in the project of distorting and erasing our history since the very first encounter.

So we drift with Ta’ Muntu, having incoherent ruminations about what the archive ought to do and what it looks like in the future. He chases us away before we seriously discuss the fact that white institutions own much of the Black archive. They decide who retrieves it and therefore how it is interpreted. Before we discuss what constitutes a Black archive. Whether the works of the Trevor Stuurmans who seem to have no other ambition other than to secure the bag and appear on Vogue Paris form part of the archive. Whether the works of Niq Mhlongo will be the best in our literary archive or we can still insist on Unathi Slasha and Thabo Jijana. Which works get archived and which works do not, what are the politics behind this selection? Is academia really the arbiter of what productions get recognition and which ones are worthy of critique? Do we allow this? There is a lot to speak about but the beers are finished and grootman is getting restless. We take a taxi, next stop De Peak, Newtown.

1 Legacy Russel, On Death, Loss and Processing A (Black) Archive

2Nathaniel Mackey

3 Stuart Hall ‘Constituting An Archive’

4 Susan Hiller ‘Working Through Objects’