One element whose importance is always underestimated in human development and education is language – and one's mother tongue, in particular. Trending discourses like the ongoing land debate and nationalization of the reserve bank are important, but in my view they are not more crucial than language, for economic development. “Every language is a temple, in which the soul of those who speak it is enshrined,” – Oliver Wendell Holmes.

The Economist magazine estimates that there are 7000 languages spoken in the world today, and about a third of them have less than a thousand speakers. Thus, these languages face a real threat of extinction, and as per UNESCO’s forecast, 40% stand to disappear forever in the shortest possible time. Some of these include Iishu (Alaska), Kuruaya (Brazil) and Cornish (UK). Locally, ten South African languages appear on UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. These include “all Khoi and San languages, which are either highly endangered or extinct,” according to Lucas Ledwaba.

Despite the fact that indigenous languages were declared official languages in the ‘new’ South Africa, they have so far failed to match the growth of Afrikaans usage since 1948. With the ‘Rainbow Nation’ idea suppressing African nationalism, South Africa is left with no language that can be considered as truly national. This leaves acres of space for a minority language, like English, to dominate the number one position as a language of politics, government, technology, and education in general. What is more perplexing is that people who speak English as a first language are not even 10% of the country’s population.

The 2011 census showed a decline in six of the 11 official languages, all of them indigenous languages. This goes against section 6(2) of the country’s constitution, which recognizes the “historically diminished use and status of the indigenous languages of our people”, and places a duty on the state to take practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages. Without any known migration from English speaking countries, the English language speakers, for example, mysteriously increased to 4.9 million in 2011, from 3.7 million in 2001.

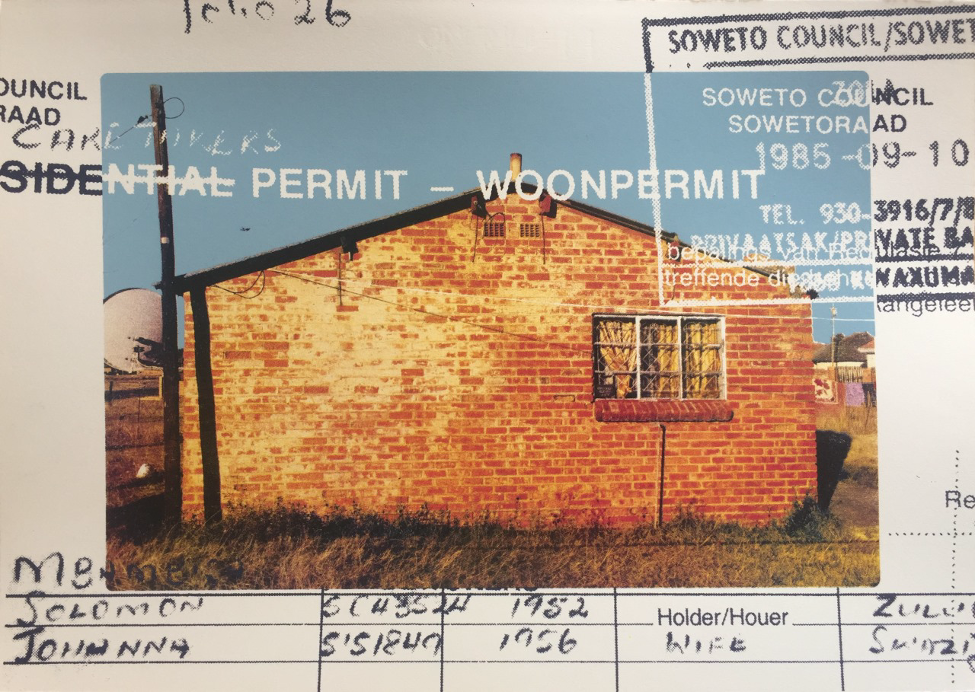

As things presently stand, the Marxist base-superstructure theory suggests that the minority white population dominates the economic base in South Africa. Efforts of the post-apartheid state to change this have been rather weak, or appear to be directed at the tertiary sections of society, including tertiary education, the job market and equity ownership in companies. Hence, all other activities, including politics and education, are inevitably aimed at maintaining the status quo and are less concerned about changing the material well-being of ‘surplus labour’ that is stuck in rural areas, townships, and squatter-camps. Therefore, this opinion piece argues that language can be a panacea to existing headaches across the different spheres of human endeavour, thus creating inclusivity.

Survival & Maintenance of a Language

The Economist says that when people think of “language death” – Latin comes to mind, but in truth this language did not die. It has been spoken since the days of the Roman empire under Julius Ceaser. However, it transmuted itself over the past 2000 years, permeating several different languages spoken today, including Romanian, Italian, Ladin, Swiss-Romansch, French, Venetian, Portuguese and Spanish. Language death happens when societies stop teaching their children a certain language, and prefer another for one reason or another. And, when an elderly member of that community dies, it is unlikely that language will ever be spoken again. The long-term implication of the death of a language is that it may be gone forever, like the now extinct flightless Indian ocean islands’ bird, the dodo.

At this point it may be necessary to indicate that there are only a few instances where a language has been successfully revived, after it had completely disappeared. In this regard, Hebrew is the only language that resurrected from the dead, after it had disappeared for over two millennia. Owing to the ideology of the national revival, this language was first re-created by Belarusian Eliezer Ben-Yehuda in Europe, and later adopted by many Jews from all parts of the world – who later settled in Palestinian lands in 1948, when the state of Israel was founded.

For Ben-Yehuda, Hebrew and Zionism were one and the same. However, he realised that the Hebrew language could only survive if “we revived the nation and returned it to the fatherland”. This is proof that language and land cannot be separated, as well as that the fortunes of a nation will flow, with this two-pronged approach. The Jews spoke different languages, including Judaeo-Spanish (also called "Judezmo" and "Ladino"), Yiddish, Judeo-Arabic and Bukhori (Tajiki), or local languages spoken in the Jewish diaspora such as Russian, Persian and Arabic. So, it was logical to use Hebrew – to build a common identity under their new state of Israel. Today, there are slightly over seven million whose first language is Hebrew.

At present, there are attempts to revive Cornish, a language that was spoken in south western England in the late 1700s. Locally in South Africa, there are languages that belong(ed) to such people as the Mpondo, Hlubi, Bhaca, Northern Ndebele, Pulana, Lobedu and Nhlangwini that are currently treated as being merely part/iterations of other languages, especially isiXhosa, isiZulu and Sepedi. In recent years, however, there have been some attempts to put some of these languages, including isiHlubi and Northern Ndebele, in written form. Raisibe Patricia Matji has argued that Northern Ndebele is a distinct language, and that if it is not preserved it could die.

In the same way as the Ngoni peoples in Malawi and Zambia, who do not speak their primary language Chingoni, the Northern Ndebele could experience what University of Malawi’s Professor Pascal Kishindo calls “a culture without a language”. Put simply, they might continue to cling on to their culture but the language (or similar) will lose out to SePedi. This may be not be said for other languages that are stronger. In terms of the ranking developed by The Economist, a language like English, which is dominant in different countries, for obvious reasons, is in a very strong position to exist for some time and well into the future. This cannot be said about the languages facing immediate death, that already have fewer speakers, like Kuruaya as mentioned earlier. Nonetheless, the majority of languages are ranked somewhere in the middle of this sliding scale, and therefore their health condition is ‘balanced’.

In some countries, governments simply ban a language, which means that people would be discouraged from speaking it. But the pressure on a language could be more ‘subtle’, thereby causing a language to suffer a slow death. One example of this phenomenon can be observed with speakers of languages such as Shanghainese (a Hu dialect) and Tibetan in western China, who are pressured to embrace Mandarin as the sole medium to successful communication. Politically, the People’s Republic of China prescribes a single state, culture, and language.

The South African Language Landscape

This brings me to our beautiful country, South Africa, which is putting the lives of indigenous languages in serious jeopardy through the overwhelming preference for English, or even Afrikaans, in politics, commerce, business, education and socially. In a way, these two minority languages take advantage of indigenous languages; by subtly co-opting people through the game of numbers and ‘economics’, to stay relevant. They act like ‘gatekeepers’ to knowledge accumulation and, eventually, to achieving economic success in life.

South Africa prides itself on being a ‘Rainbow Nation’, to signal its multi-ethnicity as reflected in different tribes and languages. The country’s supreme symbol, the coat of arms, !ke e:/xarra//ke, means “diverse people unite” in the /Xam language. Also, section 6(1) of the constitution recognises eleven official languages. Some of these languages have a national character and are more widely spoken; while others are limited to one or two provinces, as well as to fewer speakers. For example, Xitsonga is spoken mostly in the north-eastern parts of the country, and not in the Western Cape or Eastern Cape.

IsiZulu, together with other similar Nguni languages including isiXhosa, siSwati and IsiNdebele, pretends to be a lingua franca in the eastern and central parts of the country, with many speakers using it either as a native or second language. But the footprint of Nguni or Ngoni languages covers many parts of Southern Africa: from the Eastern Cape all the way to Zambia and Western Tanzania. IsiZulu/ Nguni, KiSwahili, Shangaan, Lingala and Rozi/ Sotho could easily become working languages for the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), if there was serious political will. The continent has been moving quickly of late to facilitate more trade between its countries, but no talk about a common language seems to be on the political agenda.

Wits University’s Nhlanhla Thwala asserts, “People speak a language for a reason. Increases and decreases (in usage) show which languages people find useful, regardless of whether these are their first language”. In his paper ‘The Economics of Language: An Introduction and Overview’, Barry R. Chiswick uses tools of economics to determine why people adopt a particular language ahead of others, including their own. This perspective views language skills as a form of human capital – which is productive, costly to produce, and embodied in the person.

In post-1994 South Africa, English has emerged ahead of all other languages, and is now “ubiquitous in official and commercial public life”. The educated sections of the Black population normally speak this language because it is a tool for work, and/or it is a symbol of status. As such, the majority, overwhelmingly, of the intellectual discourse in this country happens in English (and or Afrikaans), which makes one wonder how many of the sixty million people really understand what is being discussed about them and their future.

Even access to resources such as jobs, information, politics, etc. is reserved for those with a good command of English. Since many Black families understand these dynamics, they prefer to speak to their children in English. As a result, the bulk of children who go to former ‘whites-only’ schools speak mostly English, and tend to understand indigenous languages less and less. What also furthers the relegated status against the local languages is the fact that they tend to be useful only for communication, religion and nothing more. So, learning English is seen as a form of enlightenment, a stepladder of sorts, in a society where class is a dominant feature.

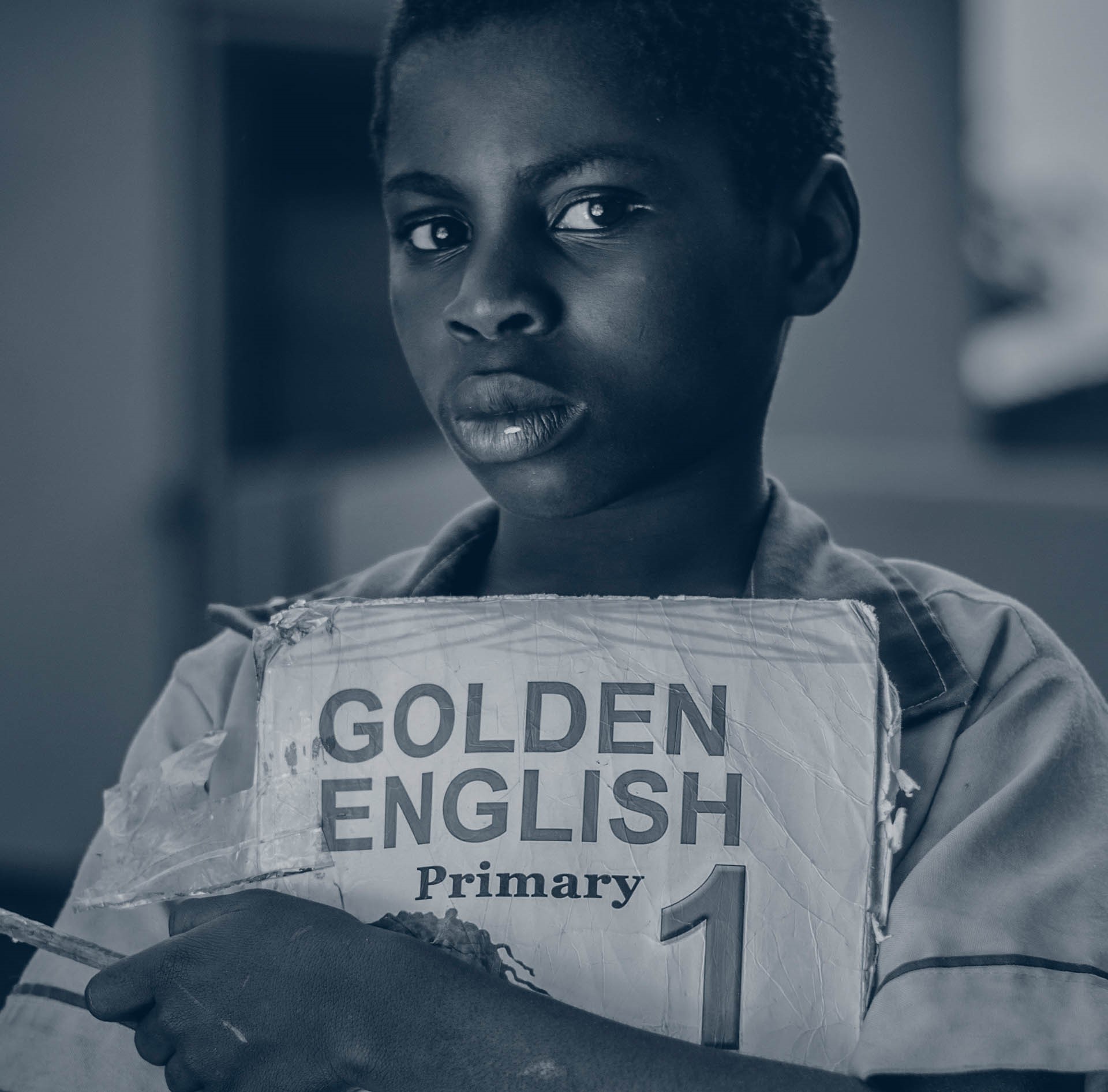

Multilingualism may have been the main ingredient for forging a new, post-apartheid identity, and for forging a new state with a unique identity, but the indigenous populations still have to derive tangible benefits from this change in political thinking – in terms of mainstreaming of their languages, especially after the 1976 students riots against sole use of Afrikaans at schools. Even more so, many do not even have access to quality education, and this cuts them off completely from learning the English language. Theirs is a double-whammy, they get inferior delivery in the right to basic education, and they cannot learn the preferred languages of commerce and knowledge creation.

Language & Development

The significance of education (language), in transforming societies from engaging primary economic activities to tertiary economic sector activities, is well documented. Countries such as South Korea, Japan and China invested heavily in education, and put emphasis on developing technologies to develop their societies. During his lecture titled ‘Secure the Base, Decolonise the Mind’ at Wits University in 2017, renowned African scholar Ngugi wa Thiong’o said, “If you know all the languages of the world but not your mother tongue, that is enslavement. Knowledge of mother tongue is empowerment; lack of knowledge is enslavement”. In agreement, Indian Minister of Human Resource Development, Ramesh Pokhriyal says, “Developed countries achieved greatness using mother tongue”.

With all the craze of political and economic integration, European countries have largely retained their languages, irrespective of size. This is based on the understanding that mother tongue-based literacy is crucial for improving educational outcomes, and optimizing economic performance. In the case of South Korea, the Korean language is at the centre of that country’s emergence as a leader in science and innovation. At present, South Korea boasts large multinational corporations like Samsung, Kia and Hyundai, which churn out new technologies on a daily basis. These companies now compete head-on with firms from the traditional technology powerhouses in Europe, Japan and the United States.

However, there are genuine concerns that in South Africa there is little or no focus on changing the nature of the system of education and training, to meaningfully help previously marginalized groups to participate fully in knowledge production. It is fair to suggest that indigenous languages can play an important role in knowledge production and the transformation of societies. Thwala argues, “We are essentially ignoring well-known facts – if you want to learn you must do so in your mother tongue. If we do not, South Africa will continue to experience high failure rates at schools and universities.”

This view is supported by a Ghanaian scholar, Kwesi Kwaa Prah, who asserts, “A democratically-based language policy is crucial for the development of a democratic culture. Without a policy, which culturally empowers mass society, development in South Africa will, in the long run, stagnate”. The current realities in South Africa as regards to its state of readiness to help indigenous populations to move away from apartheid created “permanent economic oppression” is rather appalling, to say the least. Again, Thwala adds that languages reflect the power dynamics of a country. As such, language usage is a major barometer that clearly shows us who is in charge. For example, the Afrikaner nationalists were uncompromising in promoting Afrikaans as the main language of the apartheid state.

The post-apartheid dispensation appears to take the politics of free markets a little too, far when it comes to language. Looking at the present set-up, the African majority reluctantly asserts itself in terms of language when it comes to politics, education and the media. The white liberal framework determines South Africa’s national discourse, and this stifles any prospects of South Africans being able to have “a truly multicultural national identity”. It does not matter what the views are, the truth remains that indigenous populations and their languages remain outside the ongoing political debates on creating economic opportunities for all.

The mere political recognition of indigenous peoples and their languages is not enough to transform South Africa’s economic base. This is because this recognition is definitely not commensurate with lack of usage of their languages in formal set-ups, whether it is in education, business or legislature. The newly forged identity in the South African context (rainbow nation) perhaps has a lot of political credence, but it makes little sense as indigenous people remain largely excluded from the country’s mainframe as well as economic activity.

The sad part is that the English language, in particular, remains peripheral for indigenous groups in most parts of the world, including South Africa. It also does not necessarily create or provide them with advantages to gain entry to economic emancipation and knowledge production necessary for them to compete on an equal footing with powerful nations like China, United States, Germany and South Korea. At the same, it is therefore a myth that English is a global language. Kwaa Prah estimates, “African language mother-tongue speakers does not count more than 12%.”

Even with wide usage of English in countries like The Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary or Poland, local languages are never relegated to obscurity. They are still relevant for teaching and everyday business in those countries. China and Latin America also prioritise their languages, as noted earlier. English has not taken over their daily lives, as one finds in Johannesburg or Accra. African countries, South Africa included, tend to dump their languages in favour of foreign minority languages. On the other hand, Vietnam dropped French altogether and now has one of the fastest growing economies. Vietnam also appears to have no nostalgia for the French language, cuisine and accent, as their decolonization project looks to be maturing against all odds.

Language & Africa’s Stunted Development

It is suggested that it may be necessary to complement political efforts with access to education (in their languages) in order to help Africans to create knowledge and refrain from assuming a position of consumers of knowledge produced elsewhere. Research on the relationship between input (mother-tongue education) and output (advance economic activity or ownership) of a “knowledge production function” should give us insights into understanding how societies produce innovations. This topic, of mother tongue and knowledge accumulation, as well as the language’s relevance is not all new, on the African continent. But of late, the debate is always about which language must be given prominence, in lieu of many languages spoken within countries, and of course in different parts of the continent.

Kwaa Prah writes, “The dramatic development of Afrikaans in [just over] fifty years, and the prosperity and enlightenment it has brought Afrikaners, should bring to our understanding the relevance of language to social transformation in South Africa”. This suggests that the Afrikaner experience is an important lesson for the ‘new’ South Africa because, “…continuing and future transformation in the country will have to pay full attention to the language question”. Tanzanians also grappled with which language was to be used, post-independence. As a result, that country developed a native language for use by its citizens. “Kiswahili ni lugha ya Taifa Tanzania” (Kiswahili became the language of Tanzania).

English in Tanzania and the entire East African region does not necessarily serve the role of lingua franca for the purpose of wider communication. The fact of the matter is, “cultural discrepancy between English and the diversity of African cultures renders English useless in expressing their ways of life”. Mugyabuso M. Mulokozi refers to this condition as “alienation”. This makes it extremely difficult for indigenous populations in townships and rural areas to learn the English language. As a result, people would rather use their own languages.

The scenario articulated above indicates that it is difficult for English to permeate into the everyday life of indigenous people, and this leaves them without a meaningful medium or language to participate in any intellectual activity, since many of the indigenous languages are not developed as modes for teaching science, law, commerce, economics, and politics. This situation is widespread in many developing nations, and also explains economic development challenges as well as socio-economic exclusions in those countries. Indigenous languages are neglected and face the prospect of becoming extinct, or limited to informal, non-productive settings.

Government and higher institutions of learning in South Africa are currently not investing heavily in the teaching of indigenous languages. What is almost laughable is that “most [black] South Africans are multilingual, able to speak more than one language. English- and Afrikaans-speaking people tend not to have much ability in indigenous languages, but are fairly fluent in each other’s language.” It is logical to surmise that since these communities dominate the intellectual discourse and the South African economy, and they are able to suppress debates on many issues – including the status of indigenous languages as well as their role in economic transformation.

The situation for developing nations in the international system remains extremely complex, and there seems to be no panacea for their problems. These challenges stem from weak institutions that could otherwise be crucial in the management and distribution of goods and services to their citizens. Poor policies leave these countries dependent on aid and other outside help, yet much can be achieved using indigenous knowledge and expertise, which is quickly lost with the decline in those languages. Mwenda Mukuthuria claims that, “the use of Kiswahili in Tanzania has made this country to have an edge over the other East African countries in the levels of literacy”. A country’s seriousness in developing its people reflects in policies that are put in place to help that country grow. A country shows its commitment by investing massive resources in education, and in further training – including at universities and vocational institutions.

South Africa’s Indigenous Languages Made Dialects

In countries such as Spain, France or Italy, there are many regional languages that are different enough from national languages to merit the status of legitimate languages on their own. Since these languages are not used in many different situations, but only in informal situations, they remain as dialects or ‘patois’ of the national language. In southern Europe, the Catalan language is spoken in the north-eastern parts of Spain and south of France, and some linguists therefore conclude that it is a mix of Spanish and French. In France it has no official status. But, in the Spanish region of Catalonia it is an official language, which is used in schools and in homes.

However, major Catalan newspapers such as La Vanguardia appeared only in Spanish for many years, instead of the Catalan language, until 2011. In a sense, this made Catalan a patois in relation to Spanish. This brings the Catalan fight for independence from Spain into context. Although not entirely relevant to the South African situation, the secondary usage of Catalan in Spain mirrors the status of indigenous languages in the country.

Again, using isiZulu as an example, it is a language with many first-and second language speakers, and is therefore considered a genuine, genetic language. It is for that reason it is one of the country’s 11 official languages. Ilanga and Isolezwe are two newspapers written in isiZulu, and Ukhozi FM is also an isiZulu radio station, with its headquarters in Durban. The language dominates in social circles in the country’s economic hub of Gauteng province. Many people are said to have a very good understanding of isiZulu irrespective of their mother tongues.

With such prominence one would expect isiZulu to share or even overtake English and Afrikaans, with their fewer mother-tongue speakers, in terms of relevance and usage in formal set-ups. English is a minority foreign language, and cannot be considered a national language in the same way as Spanish in Spain. It is also very different from some of the other indigenous languages, yet it remains the main language in the post-colonial period throughout the countries that were part of the British Empire at some stage. IsiZulu therefore holds a status of a patois in relation to English, hence the ‘bastardization’ of English to create an interesting mix of IsiZulu and English in urban South Africa (fanagalo). However, this should not be the case, and I argue that IsiZulu should be the dominant language for parliament, state departments, corporate SA, universities, and culture.

Laene Greene reasons that it is always sad to see a language “move from a temple to a museum…” In no time, isiZulu and or Sepedi, for example, will die a slow death and will perhaps indicate even greater marginalisation of their speakers in South African economic life.