The title of The Blunt Blades of Bravado is like a short beatbox. The alliteration pouts the lips with its B-sounds and performs the impulse to act on defence: The Blunt Blades of Bravado. It sounds out the protective pulsing of the fear of attack, but braces the body for being beaten.

There is something softly solemn to Lorin Sookool’s musing on South African coloured identity and the sense of living with an instinct to defend oneself in a world that confines you. Like living in prison, it can be a life unfulfilled. Sookool’s film The Blunt Blades of Bravado contemplates this confinement of personhood that turns people of colour into stereotypes of violence, and at the same time, the film breathes into the wound of living in constant fear.

The blunt blades of bravado are worn as headgear. Full of holes, a headpiece of white plastic knives, such as would be found in a take-away, is worn by performer Ilze Williams. The plastic knives tell of the failure of bravado. Bravado is a performance that can fail to protect.

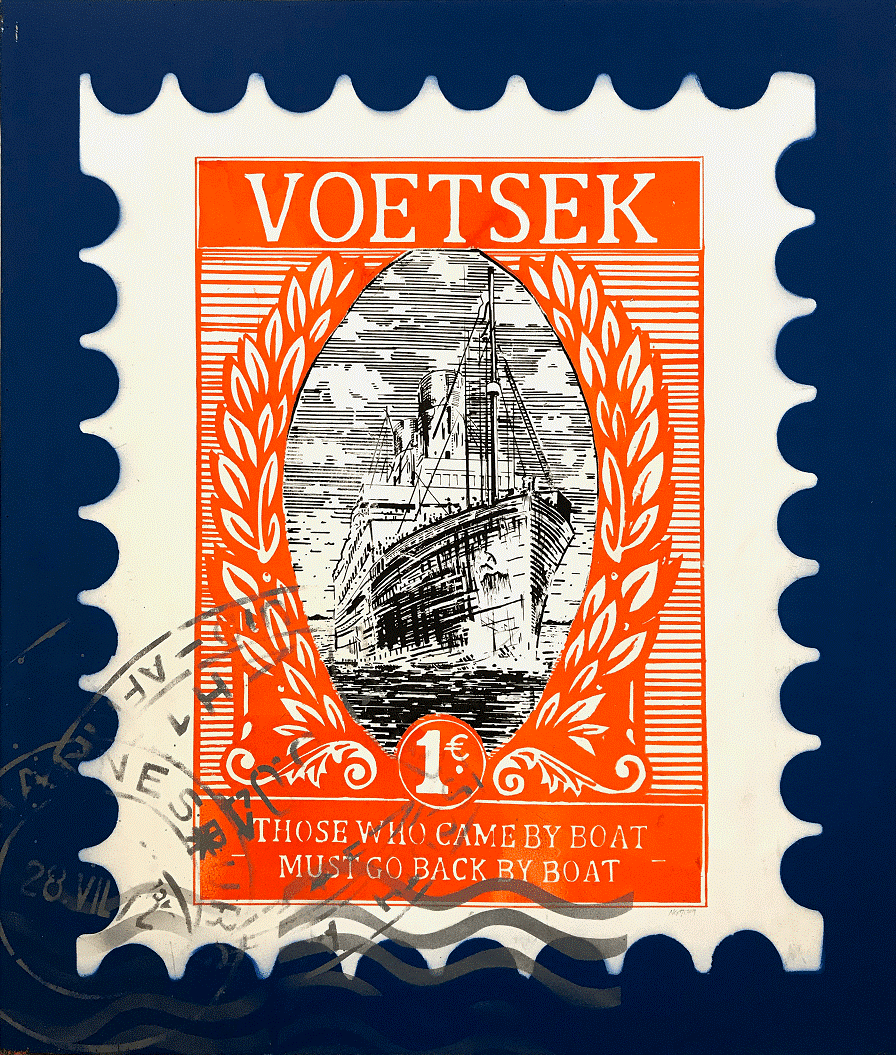

The take-away nature of the plastic utensils used in the piece also hints at the unsettled nature of the person in this state of swagger. To act brave means you are not at home. A restlessness of spirit betrays the person who must always be alert. Even as the performer moves with careful, unsurprised effort, the movement is not tender so much as resigned to its lot. It’s methodical in its effort to contain itself as though the performer silently says: ‘I don’t want any trouble’. They are not at peace. In the film, the person is in a kitchen but there are no signs of the comforts of home. There is nothing of beauty or warmth. There is a marked absence. They prepare lunch but there is no food. Sookool underscores the film with a haunting silence at the start and then cuts through this emptiness with the recorded sounds from a taxi; moving from central Cape Town to Wynberg. “Wynberg, Wynberg!”, a taxi conductor in a Cape coloured accent can be heard. The person in the cold kitchen opens a cupboard and pulls out a clean white plate, a white plastic knife, and a shiv (made out of a plastic fork and rubber band). Whiteness camouflages from colour. A radio plays in the taxi-soundscape in the backdrop. It’s lunchtime and people call in to say what they are eating. The person in the kitchen mimes making a sandwich by cutting the air with the plastic knife. The blunt blades of bravado are sometimes all that people of colour are left to consume in a world that doesn’t offer nourishment to their lives. A world that forces people to fight to live is a world where the take-away is that you must do your time and hope to find peace elsewhere.

Sookool choreographs punches in the air. Ilze Williams comes through the door like a ghost, stuck in a space of transition. The door opens and closes. Williams enters and leaves, flashing in front of the camera like an apparition. Punching the air in front of the camera Williams suddenly appears and disappears. The jolting cuts of Williams’ close-up appearance, head covered in plastic knives makes it feel as though this person is fighting both the world beyond the screen and the unseen enemies that disturb them from peace. As Williams exits and enters through the door, in the black and white silence of the first part of the film, it becomes unclear whether this person is coming or going. Sookool’s use of prison imagery punctures the possibility that this could be a person who is fighting only a mental battle. There is a system that is pointed at in the ways in which the performer leans against the door with a gentle weight. They don’t give in, but a tiredness of the fight is felt in how they stand, arms up and legs spread, as though being frisked by police. Of course the feminine appearance of the performer also hints at a womxn’s exhausted resignation to unending scrutiny and harassment, even though their resignation is in no way a passive acceptance of the system that imprisons them to always having to be ready to protect themselves.

In layers of musing, Sookool’s short film juxtaposes the public and the private through projections on the partly-covered performer, who sits quite formally on a chair near the door (no table) and eats from a shiv. A fence of metal bars, captured from a moving vehicle, ripples across the walls through projection. Like mobile jail-bars, these shadows create the sense of traveling in the outside world of the taxi-ride. Projected, they indicate there is no difference between here and there. In the cold kitchen and in the shadows of the jail-bars outside, public and private space both, feel like being held in the custody of constant threat. In the projection, Ilze Williams spins between the bars and bends arms as though cuffed behind the back. When appearing to be exiting the door to the “outside”, there is a retreat at the sense of the bars projected onto the wall. Again, the outside-inside, public-private is blurred by the projections projecting Williams in the headpiece of knives over Williams sitting and eating bravado, in the form of a make-shift weapon. The world of The Blunt Blades of Bravado is confined to this cold kitchen where Williams seems to work but not live. The exterior is projected onto the body so that, just as the bravado headpiece turned Williams into a performance of defence, the projections perform a denial of any interiority. The headspace that Williams sits inside is one of images of the outside and the sounds of a moving taxi mean that there is never any stillness.

As a meditation on coloured-identity and the systems that confine people of colour, Sookool’s film uses images of incarceration to sit with the restlessness of spirit that the confinement of an identity creates. The spiritual unrest that haunts this piece is in the lack of sustenance you must make do with in a world that threatens you. It is in having to be always on-guard, but ill-equipped with weapons that can actually protect you. It is in having to fight alone because the systems don’t recognise what you are up against. And it is in never being able to be at home, ever-moving as a ghost in-between worlds that strip you of being in the solace of your internal self, because you are always watched.

The Blunt Blades of Bravado ends with the sound of a taxi door shutting on the popular song “Jerusalema”. The song is based on a gospel hymn whose prayer is for a place called home because this world is not. The hymn asks for someone to walk with; for protection. In Sookool’s film, the door slams shut as the music builds up to ‘ungangishiyi lana’ (‘do not leave me here’). There is a plea to be seen and to be heard, to be protected and to be fed- the basic requests of living. In the film’s sudden ending, it feels like prison bars are shutting. Dabbing a blood-red serviette on the sides of silent lips, the film goes back to the black and white quiet of the beginning. A person is left to de/fend for themselves.