“No end, no middle, no beginning, no start, no stop, no progression, neither backwards not forward, only a stream that flows into another stream, an open sea.” This hollow description of a timeless life is presented by Trinh T. Minh-ha in “Women, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism”.

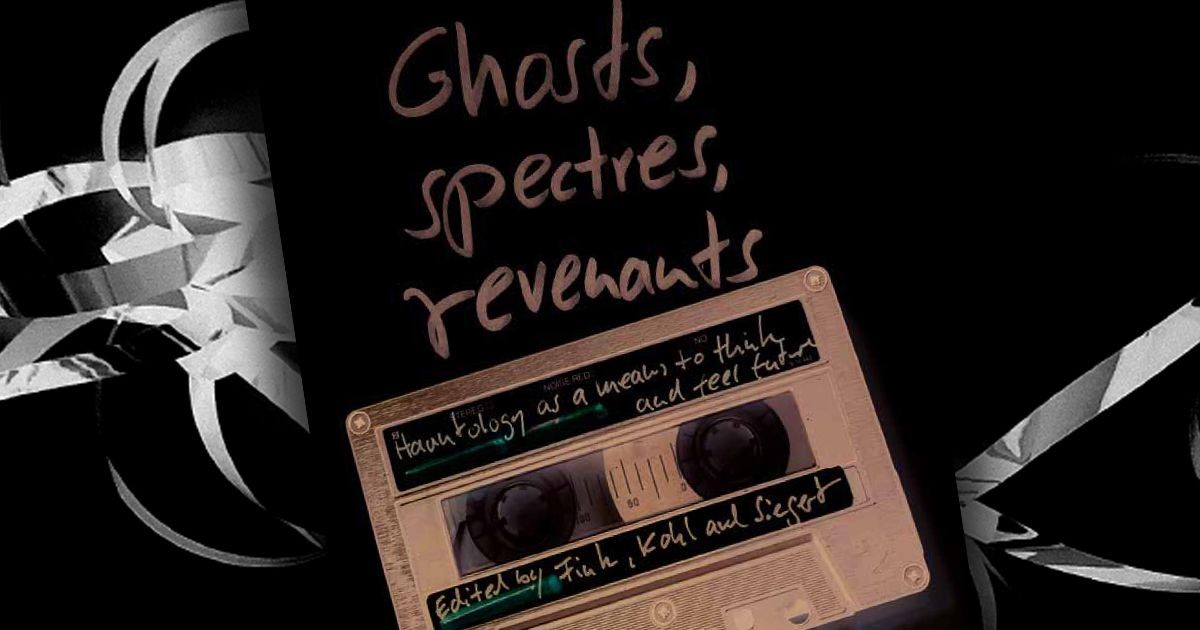

Life, especially Black life, is haunted. We are terrorised by constant persecution, the memories of our pasts and the anxieties of our future. There are many unsolved crimes, lost histories and sites where atrocities which once occurred can no longer clearly be seen -- “non-sites of memory”. We must recognise and address these phantoms. This is where the wisdom of, Ghosts, Spectres, Revenants: Hauntology as a Means to Think and Feel Future is helpful.

These collections of various writings, edited by Katharina Fink, Marie-Anne Kohl and Nadine Siegert, deliver a somewhat-exorcism (more of an acceptance) of our trauma in mixtape-essays (or interviews), preceded by two chapter excerpts. The method of this writing is interesting because it wants to exist as more than text. We are meant to hear, like mixtapes, the ghosts which haunt us. If we wish to truly understand some of the essays, we must experience the film, music or visual art they comment on. After all, the very subject of these writings is a phenomena of sense, and the exploration of the various media ghosts can take form.

Why Are There Ghosts?

And what are these ghosts? These are “disembodied voices and utterances in a choreographed although uncontrollable form”. More specifically, they are “traces of memories that surface in ghostly forms -- as sounds, smells, subtle touches”. The essay by Ute Fendler presents these ghosts as messengers which cross boundaries. Fendler analyses how they exist within the film medium as “allegorical representations of a moment that previously happened but that did not come to an end and will therefore endlessly recur”. Exploring African cinema, we see exactly how much relevance ghost stories have in communicating the links between our past, present and futures.

Political propaganda can take the form of a ghost, being present even when seemingly absent -- especially when it has been used to create historical horror. There are also sonic ghosts, present in a forgotten tune that we happen to hear again, knowing it by sound but not by name. There is the fact that young people may discover old cassette tapes as if they were a futuristic technology since they have not experienced them before. Music, after all, is recording our voices to be heard by the not-yet-born so the artist appears as a ghost to them. There are also belief systems where ancestors are connected to the present. Kolade Igabsa, writing about Yoruba temporal beliefs, describes time as a lamp on fire. There is “oil from the past, which fuels the present and provides inspiration for the future”.

A series of essays and interviews focus specifically on the ghostly qualities of cassette tapes, which crackle, intersect sonic spectra and spectre and welcome back voices from the past. Mahamat Zene Ibrahim Youssouf, born in Chad, expresses how the cassette tape brings both feelings of the past and future. Listening to his younger voice, recorded as messages on these tapes, is both hearing his younger self and regaining the feelings of the future that his younger self had at the time.

The Responsibility of our Haunting

Again, the essays ask the question. Why are there ghosts? This time, we receive a much more haunting answer. Simply, they exist to make us aware of how destabilised our sense of being is. We are already in a state of timeless trauma. Ghosts remind us of this fact. For instance, thinking about unborn generations of children can destabilise our support of capitalist extractivist economies which lead us to a “deep future” where there are no humans. After all, should we march on forward to the demise of humanity? All those future people we kill appear to us as ghosts to shake our commitment to our collective demise.

They record memory. Mark Fisher writes, “There is no way in which trauma on the scale of slavery […] can be incorporated into history”. For Fisher, all our gaps and lost names in history can only emerge as haunting. But it is also an act of future-building, through recognising the horrific ideas of the past and actively choosing an alternate future because of them. If after all, “multiple dimensions of presence” are possible right now then a different future is possible too.

Ghosts become alive to remind us of past violence. Viviane Saleh Hanna claims that western institutions are haunted by the ghosts of their victims, and their memory lay in survivors who exist as a “stant reminder of racial colonialism’s own failures, blood-thirstiness and savage ways”. Ghosts are the responsibilities to address these traumas.

Literature and film have also used ghosts to propel characters to act. Fender presents the Euro-African films, “O Espinho Da Rosa” (The Thorn of the Rose, 2014) where a lawyer pieces together the death of his lover by visiting her grave and “A Ilha dos Cães” (Island of the Dogs, 2017) where ghost dogs protect an island’s inhabitants from tourism business interests. Music is used as a form of healing in “A batalha de Tabatô” (The Battle of Tabato, 2013), which does not explicitly use ghosts. Fender also references Soleils (2013) where a hunter-figure is able to transcend knowledge and time, taking the protagonist on a journey through African history and memory.

A very recent example, not mentioned in Fender’s essay is Mati Diop’s Atlantique (Atlantics, 2019) where drowned workers inhabit their girlfriends on the shore to receive the money they are owed.

In all these films, the presence of ghosts have a purpose. They are far-separated from Western canon revenge ghost-stories (Hamlet, Lion King) and instead want to converge different colonial epochs, liberatory interests and resolution of the past. These ghosts are motivated by a clear political motive nested in colonial or imperial injustice.

Does Remembering Hurt or Heal?

We (un)consciously forget the past. Trauma is itself “non-remembering hardship or horror” as Nadine Siegert presents. “We human beings keep repeating history, because we don’t know the histories that haunt us,” Ingrid LaFleur contends. LaFleur, from Detroit in the United States, made a video about the horror of the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia, in order to be aware of how these atrocities come about. For LaFleur, people who do not engage the true horrors remain ignorant of those atrocities and do not act to address them.

This thinking is challenged by Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja who argues that local Namibians are re-traumatised by graphic re-enactments of the genocide. “My body comes from the bodies that went through this experience”. Mushaandja argues that these bodies still experience violence, poverty, photographs of skulls and even when within denialism, hold trauma. This links to a different section of Ghosts, Spectres and Revenants which mentions how someone who survived a Nazi concentration camp might have left but the camp did not leave them. In fact, various essays explain how ghosts haunt particular spaces where atrocities occurred, especially areas that suffered colonialism, genocide or fascism.

Anyone who facilitates healing has a responsibility to create a safe environment for the people being healed, such that methods which harm are not methods which heal. But Mushaandja also asks whether re-enactments have brought up greater consciousness and healing, pointing to how flawed the methods of teaching have been -- to just put information before people might not be effective.

Healing may only occur with material changes to the world that created the violence in the first place. So, memory is not necessarily an act of healing in itself. It can indeed reintroduce trauma. At the same time, non-memory can prevent people from taking actions which would lead to healing. It is an unresolved dilemma.

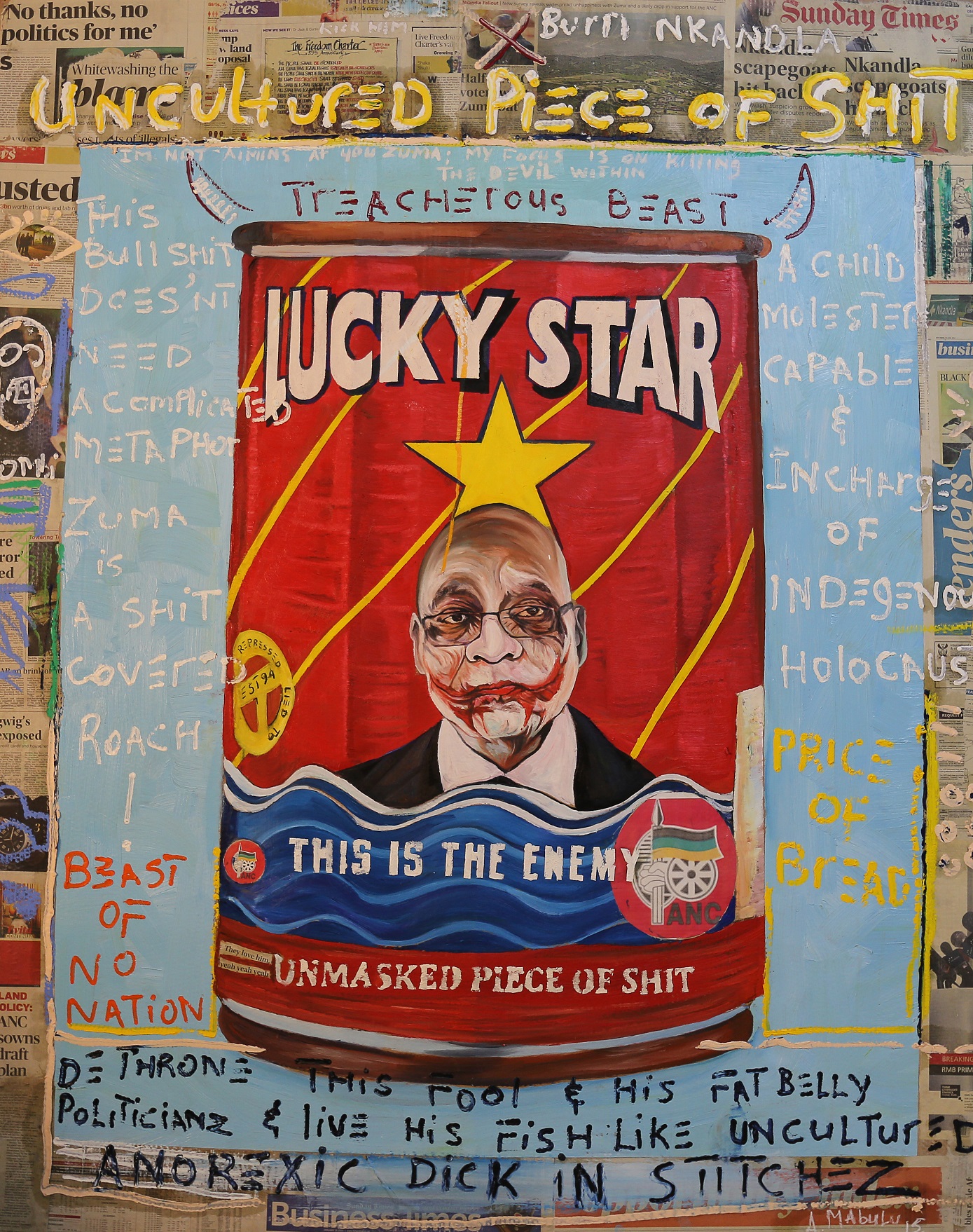

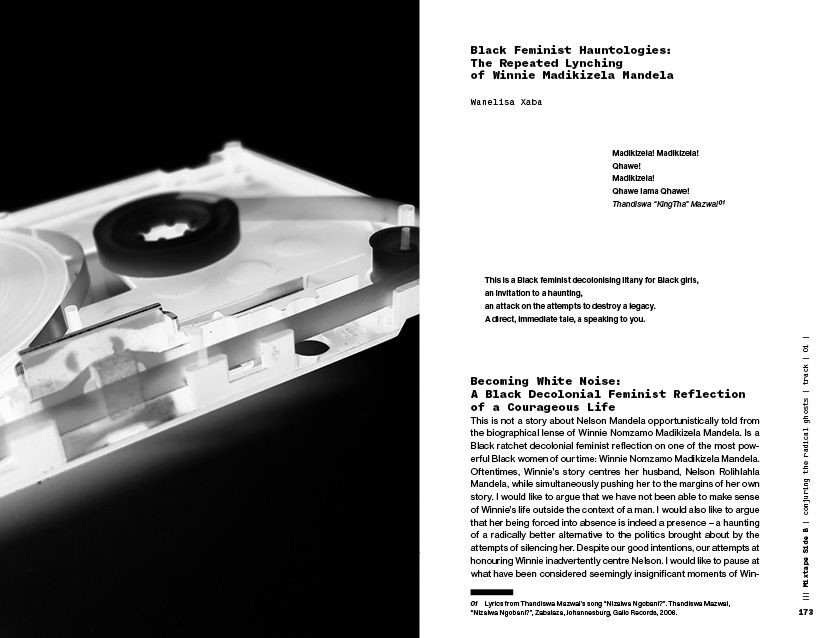

This seminal work packs multiple writers, philosophies and visual artists in ways that are best explained only by the book itself. Almost every page presents new insights. Summarising the work is challenging because a certain essence will always be excluded. The essays are themselves presented by different authors with varying interests. For instance, Wanelisa Xaba presents an essay on Winnie Madikizela Mandela’s sub-consideration under Nelson Mandela. This absence itself presented as the presence of a ghost. “Patriarchy haunts our lives and creates phantoms of our activism”. Xaba states also that this fact will haunt the Black community until we recognise it.

A large part of the text is presented as interviews with writers and essays on hauntology within art, specifically music. There are also literal mixtapes presented, wherein the music addresses the themes of the texts, sometimes through the use of historical samples or explicit lyrics calling upon the ghosts of political icons.

Instead of summarising and reviewing the content of these different writings, I wish to unpack the underlying philosophy of this book as motivation for people to consider reading the wide array of content it presents.

We are presented with political work in the category of postcolonial literature. After all, the book advises us on what to do about our ghosts. More specifically, the ghosts exist in the first place because there is something that we need to do -- encounter our trauma, change our way of life, uncover our histories, feel some responsibility for victims of oppression, prevent future people from being oppressed etc. If we wish to no longer be haunted, we must change the conditions of the world.

But prior to this political category, this is a heavily philosophical work, building from Jacques Derrida’s concept of Hauntology, as presented in Spectres of Marx. Derrida was writing to the post-Soviet expansion of global capitalism and a supposed end of history. He introduces our ghosts as “others who are not present, nor presently living, either to us, in us, or outside us”. In doing so, Derrida removes the linear thinking of ghosts as spectres of the past, introducing any “other” who is not us -- that may come about in the future. Derrida wants us to feel some sort of responsibility for even those in the future and by doing so, we shatter the linear conception of time, since we are feeling forward. So it is a work that asks us to reimagine time and the responsibilities that we have, while also challenging current structures of power, such as colonialism and capitalism.

Ghosts, Spectres, Revenants continues to touch on world-ending themes, nonetheless the present ecological crisis. So, certainly the text must be political, trying to tell us what decisions to take. For Derrida, “no ethics, no politics, whether revolutionary or not, seems possible and thinkable and just that does not recognize in its principle the respect for those others who are no longer or for those others who are not yet there, presently living, whether they are already dead or not yet born”.

Connecting Afropessimism and Afrofuturism

But foremost, this book wants to explore ontology (being) and how we are within this world. Readers may already be familiar with critical theory, which exposes us to the structures of power in the world and makes recommendations on what to do about them. The most crucial distinction that separates postcolonial thinking from different schools of thought is to look at social conditions of identity, consciousness and haunting as means of existence -- and it is for this reason that postcolonial texts such as Black Skin, White Masks (Fanon) and Afropessimism (Wilderson) are considered auto-theory, which is to write from one’s experience. In Ghosts, Spectres, Revenants, there is much auto-theory, noticeable for instance in Nthato Mokgata’s brief, Haunting Township Tech.

After all, how could we explore any condition of identity outside of our identity? This explains why most of the writers contributing to Ghosts, Spectres, Revenants might not be traditionally considered “philosophers.” Their work is presented in novels, political essays, films and visual art exhibitions. It is cemented in their identity and experience -- and by doing so, allows their work to address its ghosts. We cannot come before these ghosts unconscious of ourselves.

That is also why the text is able to collect material from a wide array of feminist writers, such as Saidiya Hartman, Octavia Butler, Christina Sharpe and Zakkiya Iman Jackson and even visual artists like Kitso Lynn Lelliott and Trinh T. Minh-ha. The magic of the text is how it weaves various different writings into a central logic.

For instance, the belief that Black existence is tied to slavery, social death and vertigo (Afropessimism) seems in conflict with the ways in which Black people interact with technology to produce new aesthetic (Afrofuturism). However, this books shows how Butler’s novel, Kindred, features a time-travel plot line which enforces the idea of Afrofuturist trauma, where even the devices we create in the present (or future) are connected to the trauma of our past, making those traumas in fact existent in the present and future as well -- and so not just past trauma. This idea intersects with Sharpe’s scientific exploration of whale falls in the ocean, used to premise the idea that the atoms of slaves are still actually present in the nutrients within the ocean. Most profound is how the text explores Butler’s concept of alien time -- “instability, insecurity, and dehumanization … a constant threat and ongoing horror”. What this means is that there is a possible intersection between Afrofuturist ideas of technology, science-fiction, time-travel, exploration and creation which intersect with trauma -- therefore, with ghosts.

There are also various forms of art which visualise or express our temporal connections to slavery. Lelliott creates an exhibition which by displaying different scenes of slavery, such as the Atlantic Ocean, elicits a visitation to that space -- but also that time. “The body has a history which is inscribed as a place of occurrences,” presents Danillo Barata in an essay about connecting Senegal and Brazil as spaces of African heritage through art installations.

Lelliott also presents various different systems of time from various mythologies predating standardised meridian time, asking us to think differently about temporality -- and even how our bodies can be media for travelling through time. The book further presents how Techno music duo Drexciya explore this theme in the liner notes of their album The Quest. In this album, they explore being “offspring of pregnant Africans who were thrown or jumped overboard and moved from the amniotic fluid of the womb to the ocean water and were thus able to adapt and build an underwater city”. This sort of art moves us to a not-yet-come future world through moving backward into the past.

There is also Achille Mbembe’s work on necropolitics, which suggests “forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life that confer upon them the status of living dead (ghosts)”. Think about how the destitute and especially migrants are isolated from general society to the point where their living conditions are akin to ghosts. This entire outlook on societies, laws, ethics and culture is also wrapped into the concept of social death. So, multiple philosophical inquiries converge within hauntology.

Revenant and Arrivant

The ultimate resolution is that we are acted on by two temporal pulls: “the pull of the no longer […] and the not yet”. There is the force which causes us to repeat our trauma and reinforce the structures of the world in a “fatal pattern” and the force which attracts us to some future, shaping our attitudes and behaviour in anticipation. Derrida calls this “effective as a virtuality” and “effective as a virtual”. He considers that ghosts appear to us as revenant (returning from the past) and arrivant (arriving from the future).

We can consider climate change (negative arrivant) and communism (positive arrivant) as spectres that arrive from the future, announcing what is to come, as motivations for the kinds of actions we need to take today. They are “the persistence and lingering of failed, omitted and often utopian ideas that also formed radical visions of the future”.

We cannot exorcise these ghosts without changing the conditions that lead to their arrival. We could reassure ourselves, in our minds, that capitalism or human existence, will not come to an end. But such ghosts will always return. After all, we are haunted precisely because we expect future re-appearances of a ghost. It therefore comes from both the past and the future, alerting us of what has happened and what is to happen.

Accept the Haunting

Many try to not be disturbed by the ghosts that haunt them, such as not thinking about the future-to-come which the ghost presents. This is because recognising this disturbance motivates us to exorcise the ghost, which means addressing the conditions of the world. Instead, we should let ourselves be disturbed, even if that comes with uncertainty about the future. Will we avert the ecological crisis? Will colonialism come to an end? These are uncertain questions that once sunk into us force us to act. This also means that the future presented by ghosts is not a certainty. After all, neither is our knowledge of the past. Both are presented to us by these ghosts.

Ultimately, when we do act, we are acting on an imagined future. Who can be certain that a nuclear war will happen? But we can certainly feel the possibility of such an event from the haunting of the future. It is this uncertainty that we must live with and accept. But at the same time, imagination also allows us to move from the “future present” which is the future we currently are moving toward and the “future anterior” which is the future that might be.

Being haunted means precisely allowing ourselves to be uncertain about the future in order to take actions to address it. If we allow ourselves to believe in social death, timelessness and vertigo, we move away from the assumption that we are on the path of progress -- and by doing so, find ourselves on that very path. “We can only face the future in a way that could make it otherwise if we allow ourselves to be haunted by a to-come that we can never be entirely sure of”.