These songs of ours always get us into trouble. When we want peace, we sing. When we want to be heard we sing. Sound permeates our lives and like Fela Kuti said; Music is a weapon. Pipe smoking elders in Zimbabwe who spend lazy afternoons playing Mbira say a grunt in a chant spells trouble. This is the free voice of Afrikan music. I link its poignancy and articulation of the Afrikan resistance to cultures and social groupings across the continent. Our healers say freedom music is the healer. Once, I heard soldiers toyi-toyi in the dead of the night in Mutasa, Mutare during the second Chimurenga war and I knew that freedom music was the exit point of our frustrations. It’s like a punctuation in a reggae beat or the protesting horn of an Afrobeat track. It is our remedy to forget – even if it’s just for a few minutes. Over the years, I have come to understand freedom music as the soundtrack of our lives. Freedom music comes from the heart. It articulates raw emotions – good or bad. Music is like a balm on chaffed souls. It soothes and energises the body and spirit.

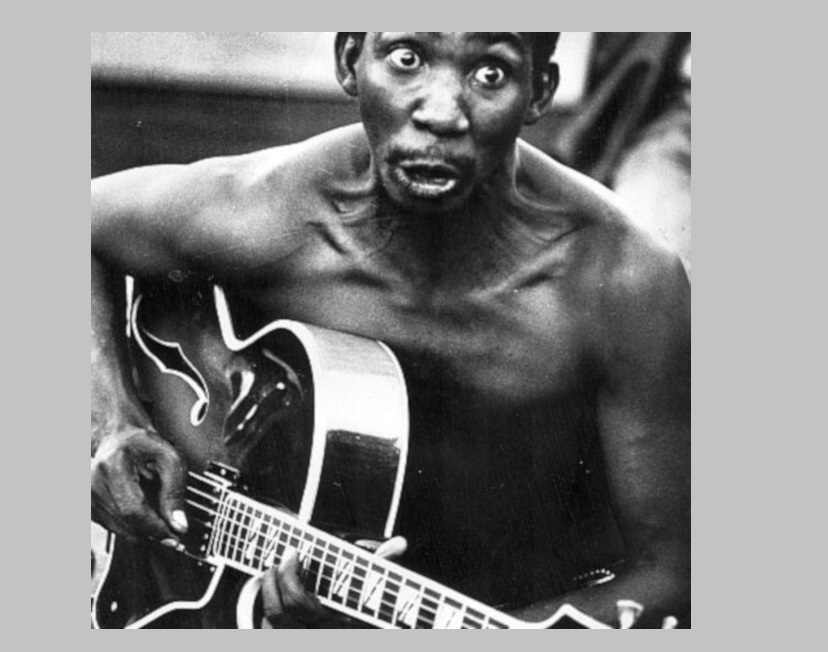

In my grandmother’s kitchen, two things occupied the walls – a Chipendane and a bow. They represented harmony and protection for our family. This is the backdrop of Free-Dome music. I call it this because its potency lies in inciting the mind to question social realities. Our musical tradition has been developing bar lines of freedom music from antiquity and it’s safe to say that King Shaka’s battle cries were composed and choreographed to serve as tools of intimidation and self-confidence. Traditional music does not live in a concert hall. Compositions of melodies and lyrics are created with community performances in mind, and these compositions do not seek to combine sounds to suit a particular taste. Their purpose is to express life – culturally, spiritually and socially. Another aspect of our traditional music is its ability to fuse natural sounds with spoken words to create music. This is where the pattern of self-expression gets accentuated. We can find this in simple structures of Malombo music or the haunting melodies of the Jeliya of Mali.

Freedom music is rooted in self-expression, but most importantly, it is an expression that portrays community outlook. To the trained ear, traditional music gives an impression that pentatonic scales, hexagonic scales or polyphony are used but the secret lies with the untrained ear – it’s the translation of emotions into sounds. It is an outward presentation of our thoughts and feelings. Social progress within communities also causes the need to use songs to express certain milestones.

Afrikan compositions tell stories that bring colour to our everyday lives. There are songs for weddings, work, hunting, farming, death, and fishing. Music also symbolises birth in many African cultures. We are bound to the drum both in communication and in rhythm. Colonisation brought with it a different perspective not only on Afrikan lifestyles but music. The systemising of education created learning and with it came Anglo-Saxon schools and churches. These institutions became the training ground for music in what is known as Choirs. This new platform created a new found symbiotic relationship between religion and revolution. We cannot deny this fact. Musicians in early tribal wars produced many songs of revolution and proclamation. They became the repositories of community and family history but also the first voices to communicate the community’s feelings. They captured the essence of living and cultural philosophies.

This early development of freedom music helped to fuel the fire that enabled Afrikan nations to defeat imperialists. In South Africa, music was the weapon that gave comrades courage to keep up the fight. The same was experienced in Namibia, Mozambique and Zambia. Bob Marley incited comrades in Zimbabwe to rise and claim their land. The early settlers on our continent brought with them many things but none more life changing than schools and churches. Before this time, people praised the creative creator. They tuned into this creative force and fashioned songs of joy and awe. The Western approach to music and religion created a meeting place that gave birth to choral music. A lot of our compositions took on this early developing route of which gospel music played a critical role. It started flourishing in small communities across South Africa, but it’s important to note here that this change did not remove our ability to express our true emotions. During these early days, new cultures and continuous displacement overwhelmed South Africans. The reality of living in one’s own land as a foreigner was frustrating Africans and in their efforts to appease the almighty, western religion took hold of our mothers and through them singing was re-fashioned and directed at the creator asking for salvation, and relief from oppression./p>

The South African natives caused commotions with their songs of hope, freedom, and redemption. The dawning of the 20th century brought with it events that transformed South Africa and also resulted in a free society we live in today. Until 1949, lyrics did not court political confrontation mainly because black politicians in those days belonged to a select few elites. These black elites were mostly intellectuals and possessed a dualist’s mind. This idealistic state got short-circuited by a gentleman famous for a futuristic contribution to our history– “Nkosi Sikele i Afrika”. Elder Enoch Sontonga composed a hymn that asked for blessings and salvation for people of the land. This song was a major turning point in the evolution of freedom music and it spread across Southern Africa. Dr. Cornell West says one cannot remove religion or Christianity from liberation struggles and he is right; Elder Enoch’s song transcended the dualistic idealism and evolved into a liberation song of unified hope. Countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa honoured elder Sontonga by using his lyrics their national anthems.

Dr John Dube of the Ohlange institute amplified Elder Sontonga’s composition through various performances. This twist in the journey of South Africa’s freedom music changed the way music was composed. It brought with it emotive driven melodies. Songs began to express feelings of the day, such as the Song of Oppressive act. These kinds of songs married politics and music and gave birth to various genres that used songs to reach the young and old. Gone were the black elites who occupied high chairs. The wheels of liberation had started to turn. Music became a political weapon and a loudspeaker of retaliation. Songs like “Umteto we land act” became the blueprint on which the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) declared their intention to free South Africa. This organisation changed its name to the African National Congress (ANC).

The state of the nation became the subject of many songs. Militant lyrics became the stuff of thought and some old songs like “Senzenina” took on a different meaning. Freedom music also had African American influences which to a large extent were sparked in 1891 by Orpheus McAdoo and his Jubilee singers. Black South Africans identified with their African American brothers and composers shifted their styles (i.e. Rueben Thokalele Caluza’s Ragtime compositions) to fit in with the flavour of the day.

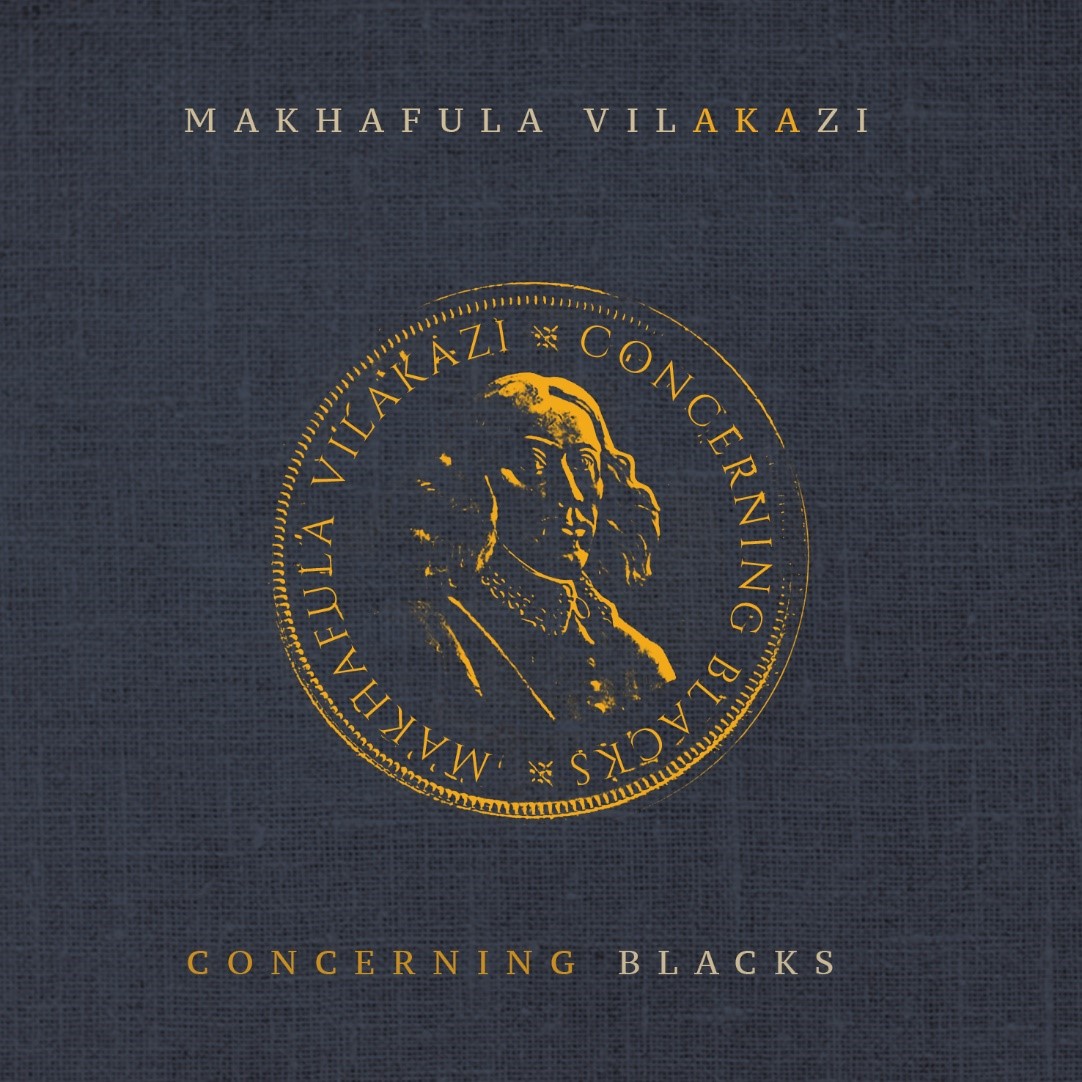

Between 1920 and 1993, compositions became a blend of nationalism with moral/Christian viewpoints. They articulated deteriorating socio-political conditions and the evils of the godhead. Songs like “I dipu eTekwini” articulated one of the most de-humanising aspects of apartheid. It called for a condemnation of white city administrators who introduced a new dispensation that required all black work seekers to undergo “deverminisation” in dipping tanks for public hygiene. A few South African musicians found their way to other continents and continued to spread the message. Whilst Hugh Masekela, Letta Mbulu and Miriam Makeba were setting the scene is America. Johnny Dyani was grooving to Song for Biko in Denmark and later on in Botswana as part of ANC’s Festival of Culture and Resistance. Freedom music was now in the hand of global South Africans whose sole careers became intertwined with freedom of Azania. In the homelands, political groups were being organised and they educated members through song. They used extended melodies with words to tell their situation. The American connection stayed strong in the form of jazz compositions by the likes of Dudu Pukwana, Kippie Moeketsi and Abdullah Ibrahim. The melodies of freedom songs took on a different groove driven by the evolution of jazz within black society. Township life began to grow as more people from different parts of the country moved to big cities in search of work. Masikandi and Mbaqanga were addressing the order of the day. Lucky Dube’s Prisoner and Leta Mbulu’s Uhuru propagated the never-ending struggle of native South Afrikans to gain independence. The behaviour of native South African began to shift to adapt to new environments, and the direction of freedom music followed suit.

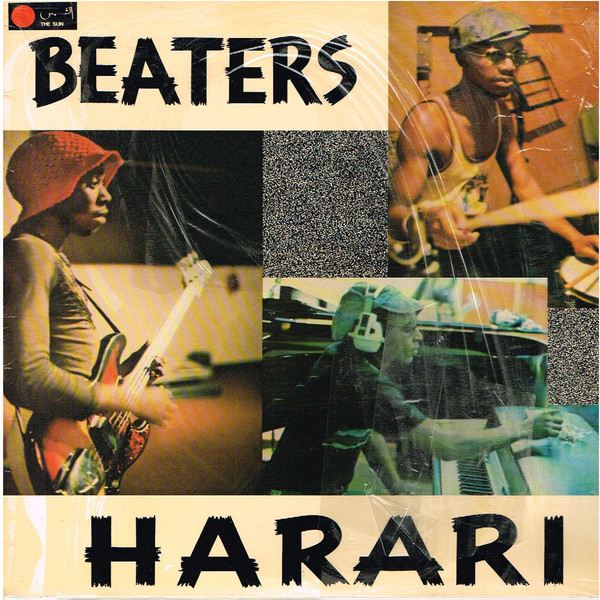

The era of Motown and bump jive showcased urban living to the masses and with it the heightened activities of political ideologies. This change saw Sophiatown emerging as the haven for gangsters, priests, musicians and political debaters. The Sharpeville massacre and the 1976 uprising took a lot out of people and the need to fight the oppressor heightened. Musicians started using their popularity to push the political agenda. Groups like The Beaters used their musical instruments to smuggle youngsters into exile to join the liberation struggle. The death of Hastings Ndlovu in June 1976 in Soweto triggered wide spread violence in South Africa. Feet shuffling and toyi –toyi were amplified by freedom music. ‘We shall overcome!’ they sang, defying the false hope the sun brought. This attitude became the spirit of defiance that swept the nation from villages to townships. Old songs underwent changes to reflect the mood of the people and one such example was the song ‘Senzenina’ which asserted a sense of worth and belonging for the common man. It also critiqued the political climate calling for recognition of the African voice within.

The 80s brought accelerated urbanisation and its influence on American music. People like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were symbols of association and musicians began to take on a philosophical approach and the emergence of social consciousness through the powerful sound of Reggae Music. South African greats such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, and Abdullah Ibrahim used their exile status to push revolution through song. In fact, all exiled musicians took on this stance and artists such as Kippie Moeketsi, Lefifi Tladi and Johnny Dyani debated freedom in South Africa through musical compositions and poetry. The African experience caused this and through freedom music, Mbaqanga and township pop created a cacophony of songs that addressed personal experiences, political, and social oppression. Lucky Dube featured prominently and through his music, the plight of Afrikan natives to the global community became a talking point. Remnants of early forms of freedom music echoed in compositions by Gospel and Jazz musicians. This era highlighted the growing frustrations of oppressed Afrikans and the need for freedom. The ANC cadres used music to spread their message. Thami Myeni’s Medu projects in Botswana use both art and music to chronicle the changing voice of the people. Farm workers used songs to protest against the oppressive working conditions that continued to deprive them of economic freedom. The singing tradition continued in many parts of the country and fuelled protest marches that eventually resulted in apartheid being abolished and the ushering of a new era for Afrikan natives.

The message changed in 1994 and musicians in South Africa and abroad found a new voice. The effects of apartheid still endure until today, and the emergence of popular culture sparked a youth movement that used music to talk about urban living, education and economic empowerment. Kwaito music was born with hints of a rebellious disposition. This genre of free-dom music was and still is the most potent urban music to come out of Johannesburg and it drew attention to living conditions in townships. Arthur Mafokate’s hit song ‘kaffir’ reflected the new freedoms that emerged after the political changes of 1994. The song’s lyrics were fiery and addressed the classist society that placed the native at the bottom of the food chain. Music became a tool for young people to bring attention to their own communities and expressed an attitude of self- expression, self-reliance and determination. Kwaito remains a fiery genre conceptualised by township youth for township living. Many other artists such as Boom Shaka, Trompies and Brothers of Peace epitomised the changing signs in South Africa.

A genre that revolutionised freedom music came in the form of Hip Hop music. This genre emerged as another powerful voice that had its history in praise poetry and slave songs from America. Prophets of the City, Black Noise and the iconic Open Mind Sessions in Johannesburg gave birth to a new Pan Afrikan voice that used music to ask questions and to project a positive outlook. Artists such as Public Enemy, KRS – One and Poor Righteous Teachers influenced the modern song of the heathen is Africa. Today, hip-hop music has become the number one genre in the world because it allows the voiceless to express themselves in their language with their own style. Freedom music is alive and well as seen through the works of Stogie T, Sifiso Sudan, Tidal Waves, Lesego Rampolokeng and many other acts that use their artistry to effect change.

This is but a snippet of a story that can be told in a million ways. I guess the question to ask is; Is freedom music still relevant today? We are in the throes of globalisation after all and the protest principle has sailed the worldwide wed as witnessed in North Africa. We have been entertained by the politricks of Afri Forum and Julius Malema dancing around the Dubula iBhunu song or Jacob Zuma’s gymnastics to Awuleth’ Umshini Wami. Do these events project a world that is changing and in need of a different tune? I believe the role of freedom music is yet to be exhausted in our communities. As much as the lyrical content could be mistaken for hate speech in some quarters, the historical importance of such songs cannot be trivialised. Self-Expression remains a cornerstone of freedom and we need to do all we can to protect it. The Afrikan revolution has not yet been realised and until then the Heathen songs of the natives should be heard and continue to be composed. We need them desperately.

This article was first published in the Liberator Magazine’s anthology: Last Generation of Black People Charles Nhamo Rupare’s position in the universe is at the place where music, entrepreneurship, energy, writing, travel and agriculture intersect. He currently resides in Johannesburg and works across the Afrikan and other parts of the world.