Theatre of Violence (2023) narrates the trial of Dominic Ongwen, who was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army and grew to become a ranking member of their insurgency against Ugandan President, Yoweri Museveni.

NORTHERN UGANDA IS A STAGE FOR VIOLENCE

The documentary opens in media res, as the International Criminal Court explains that Ongwen has been indicted on multiple counts of sexual crimes, war crimes, crimes against dignity and crimes against humanity.

Ongwen’s chief counsel, Krispus Ayena, acts as the principal character to narrate the complexity of the ongoing war in Uganda, the philosophy which underpins its violence and how that connects to Ongwen’s trial at the Hague. The cast of the theatre of violence are expressed as follows:

- ●Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni, a despot who captures innocent Acholi to execute them or force them into internment camps.

- ●Joseph Kony, an Acholi rebel who formed the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) as an insurgency against Museveni. The LRA abducted and indoctrinated a nine-year-old Ongwen.

- ●Spiritual leaders, such as Achama Jackson, who express Kony as a prophet, edifying the LRA and their use of violence,

- ●Acholi traditional leaders who helplessly witness the abductions by both Kony or Museveni,

- ●Dominic Ongwen, an abducted Acholi child from Northern Uganda, turned child-soldier and then commander within the LRA,and

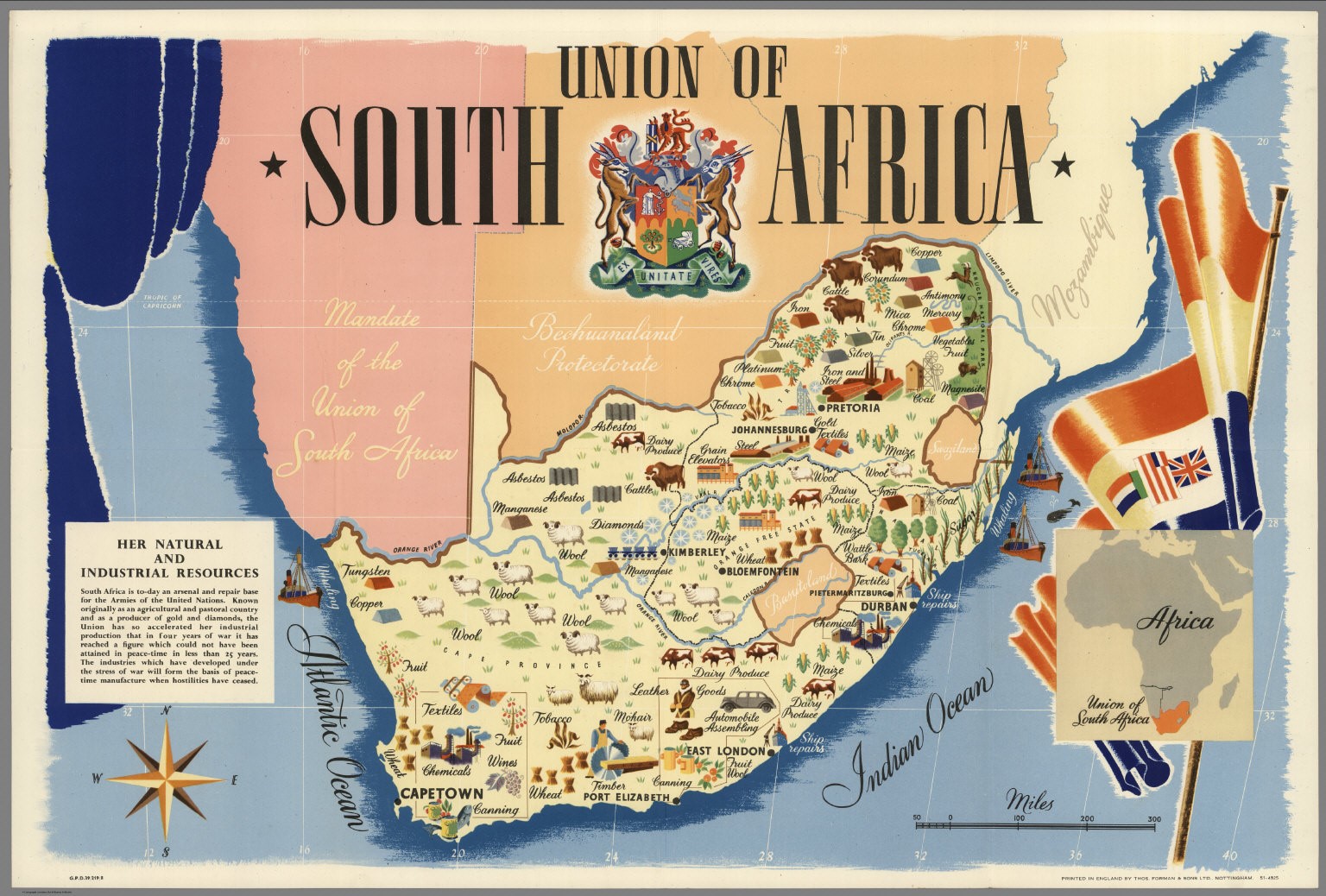

- ●The underlying actor of colonialism which sprung the region into a violent environment where violent actors like Museveni and Kony thrive.

Northern Uganda is thus shown as a scene for the play of violence.

ALSO READ: Museveni’s Rigging & Legging

Various victims, such as one of Kony's wives, and victim-perpetrators tell their stories. Locals comment on their support or disdain for the ICC and the trial. The documentary captures the variety and complexity of affected parties.

Bobi Wine, a pro-democratic candidate in 2021’s presidential election, empowered by youth who want a change in government, is shown as an actor working toward peace. Yet, the documentary shows the intimidation of Museveni’s armed forces, incidents of election violence and the ongoing stage of violence which led to the events of Ongwen’s trial.

DEFENCE OF ONGWEN

The documentary does not absolve Ongwen of their crimes. Ayena explains that his counsel wants to tell a story to the Western world about the spiritualism which complicates the conflict in Northern Uganda and Ongwen’s motivation for participating in the insurgency. For Ayena, the ICC and the wider western world misunderstand the motivations behind acts of violence carried out by Ongwen and members of the LRA. There is also an ignorance to the actions of Museveni’s government in fanning a culture of violence among Acholi, which seeps into their way of life.

While the defence does argue various mitigating factors, such as Ongwen's status as a victim, their message is fundamentally about African metaphysics, explaining how it comes to be that Ongwen is a violent actor.

Ultimately, the defence proves unsuccessful, as the ICC sentences Ongwen to 25 years of imprisonment. In the documentary, the presiding judge acknowledges the context under which Ongwen's crimes were committed:

According to credible descriptions on the record he was a gifted child with an intellect far above the average. He had all possibilities to become a valuable member of his community and of society in the normal course of events. All these possibilities, all his positive potential, all his hopes for a bright future came to a brutal halt when he was abducted.

The ICC enters as an actor in the scene of violence, but solely to prosecute Ongwen. Various local voices, including Bobi Wine, see this as a bias favouring Museveni, who benefits from his rivals being imprisoned. There is no defence of Ongwen, but the sole targeting of Ongwen is shown as a problematic political decision which further empowers Museveni's violence.

A crowd in Northern Uganda watches the trial of Dominic Ongwen

THE METAPHYSICS OF VIOLENCE

In a book titled Themes, Issues and Problems in African Philosophy, Ugandan philosopher, Wilfred Lajul argues that various African groups (Yoruba, Akan etc.) believe that the human is triadic, constituted of body, soul and heart, where the heart is most central. This is because the heart is a source of emotive and psychic powers. In traditional interpretation, its beat represents predetermined psychic realities.

Achille Mbembe argues in On the Postcolony that postcolonial leaders use violence to form themselves as the psychic reality, through which their subjects access personhood and being. This explains why, despite being in conditions of abject poverty, Africans ululate and gyrate for their despotic leaders, and even re-elect them. It is precisely because they are despotic and fictitiously violent. That serves as the proof of their divinity and psychic force.

Mbembe sees expressions of excess (ululating, gyrating, etc.) as multiplied identities, which could be interpreted as new identities formed where people’s bodies and souls are inexplicably linked to their leaders, who serve as their hearts. People are then willing to lend, sacrifice or devote their bodies and souls to their leaders, as these leaders represent psychic reality.

ALSO READ: Mbembe’s Postcolony

For the Acholi, the heart is called Adunu and is responsible for the circulation of blood. But what distinguishes the Acholi, according to Lajul, is the concept of cwing which serves as the metaphysical “source of emotional and psychic reactions or the spiritual source of emotion”. These psychic realities have bearing on their concept of self, destiny and morality.

A children’s Christian choir in Uganda

The metaphysics portrayed in Theatre of Violence align with Lajul and Mbembe's explanations. The LRA's teachings of spiritualism, which are reinforced by arbitrary and fictitious violence, claim there are universal spirits (i.e. psychic realities) which are omnipresent and guide all actions of LRA soldiers, especially acts of violence. A spiritual leader, Achama Jackson, testifies to the ICC that these spirits can order soldiers to kill everyone (man, woman, child) on a battlefield even if they are innocent and unarmed.

Kony is then revered as the heart-figure in the triadic relation of being, as the source of psychic reality, through which the LRA access and meet the expectations of the spirits.

None of this justifies violence, but Ayena expresses that the ICC and the western world do not comprehend the link between acts of violence and how the LRA's soldiers conceptualise personhood, their moral responsibilities and the nature of their being. This heavily contrasts with western concepts of individualised culpability, personhood through human rights, and just war. Such considerations are weighed significantly down by the existential view of the self as subservient to a violent spirit.

ALSO READ: Olúwolé’s African Metaphysics

ENDLESS CYCLES OF VIOLENCE

Ugandan lawyer, Krispus Ayena

Mbembe argues that violence is circular. It establishes its own authority through itself, is maintained through itself and is revered through itself. The postcolony mirrors the violent relations of the colony precisely because the processes of civil society, democracy and state intervention are preceded by violence. For Lajul, such violence would have metaphysical roots, wherein the people committing such acts of violence feel compelled and justified to do so, because they are commanded by the authority of the heart. Rejecting such authority requires rejecting one’s sense of beingness in the world, the nature of existence, and specifically, the all-powerful spirits that influence the psyche. Such a task cannot be resolved through courts or institutions of individualised justice, but by challenging the metaphysical roots of violence.

The documentary ends without much hope for resolution in Uganda. Museveni is re-elected. Discussions on restorative justice are shadowed by sustained atrocities. Meanwhile, Ongwen begins their imprisonment. Nothing much else changes.

"Everything in the past, now I remember it all". Ongwen repeats, "I remember. I remember. I remember. I remember. I remember. I remember. I remember. I remember…"