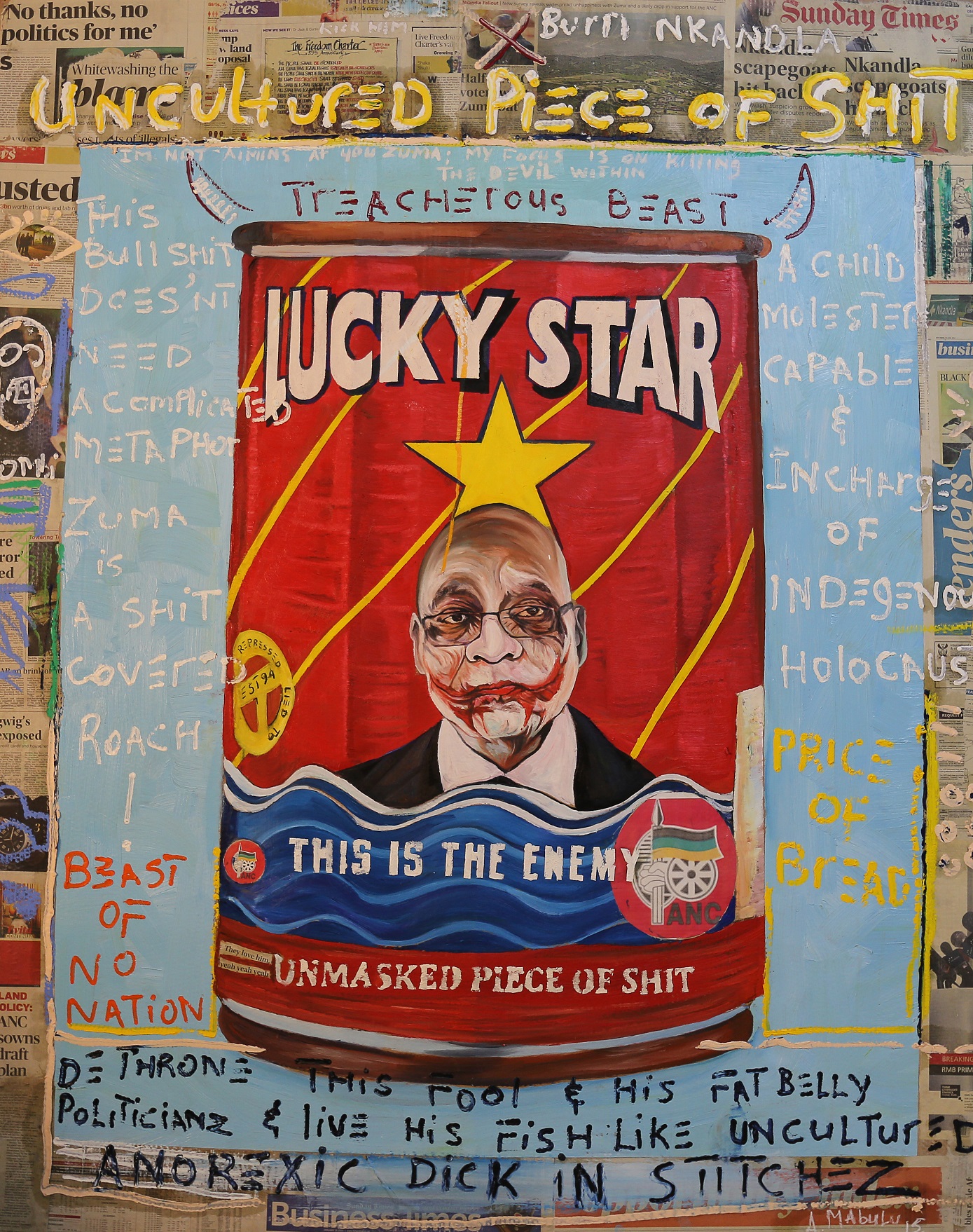

For Azanians, our lives, our experiences and existence is the copyrighted sole property of a settler minority who have appointed themselves narrators of black life. In the arts and academia, this proprietorship is the normalised reality that artists of the land have to contend with in order to collect the crumbs meted out by the free market system.

Vincent Moloi’s pantsula chronicle, Tjovitjo, is a vital response to the times – similar to a period when amapantsula of the 70s “emerged not only as opposition to the apartheid system, but also to the social structures and their home culture. The youth of the 1970s were faced with similar socio-economic to those faced today. Becoming amapantsula became one way of challenging authority and oppression…” Idah Makukule,Amapantsula Identities in Duduza from the 1970s to Present Day.

Moloi and executive producer Lodi Matsetela’s response to the contemporary meant that they sought creative autonomy and ownership of their material, something that is a rarity in the nether world of South African television.

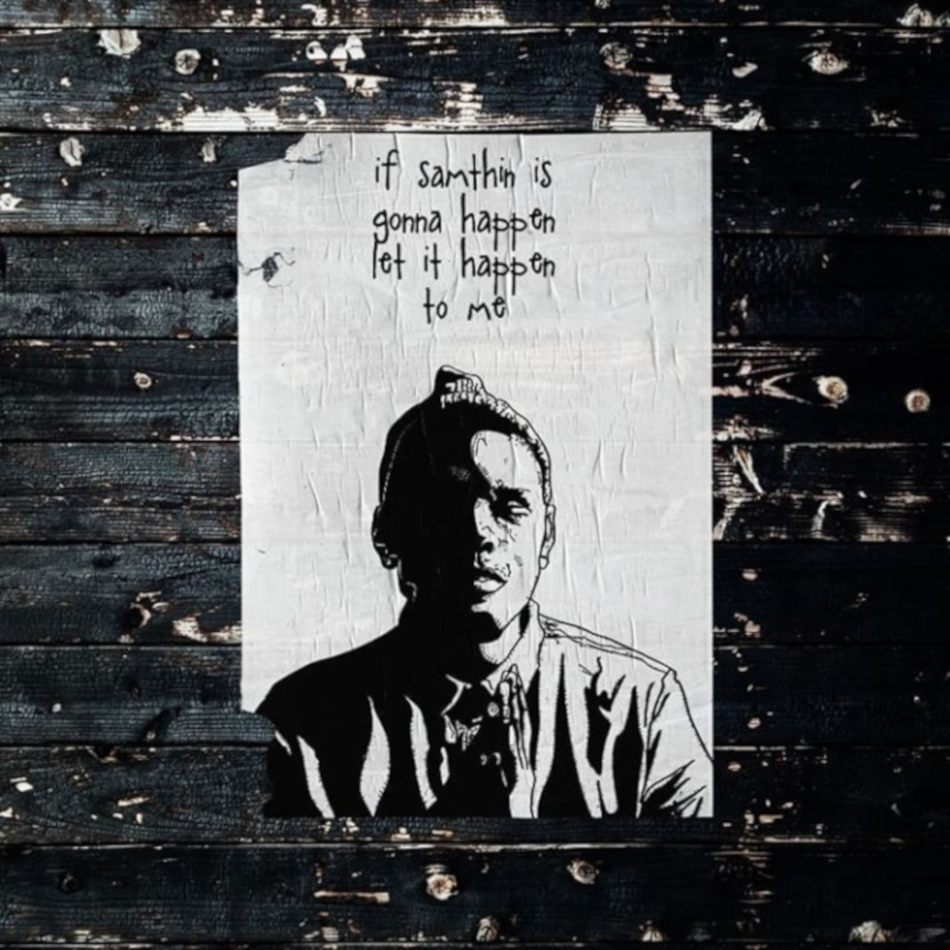

Although Tjovitjo is a Puo Pha force, it is a cinematic imposition of the director’s will. An imprint of his soul, an ode to Azania. So when the show’s lead perpetrator, Warren Masemola, hollers “Black Power” at the conclusion of our interview, it becomes kliye what the project on location out at the Crown Mines is all about.

Episode 1 Opening Scene

EXT. MAFRED’S BASE CAMP. DAY

Quick steps and slick foot movement to the beat of diegetic sounds floors to the screen, where a flurry of pantsulas are warming up. An aerial shot of the dancers, then corrugated rooftop and finally a low angle shot of smoke bellowing from underneath a washing line reveals the world of the story.

Perched upon a throne, we meet our troubled hero, Mafred (Masemola), who dons a black waist coast that reveals his bare chest. He wears an immense expression while attending to the contents that ignite his smoking pipe. Gentle musical notes ascend steadily with every considered movement until he gets up as the melody heightens to a dramatic crescendo that culminates in a kung-fu GONG!

Song follows Mafred’s movement switching to traditional musical scoring interspersed with suspense modes typically heard in Westerns as he limbers up to Jairus from Trompies. Before Mafred, is an assembly of finely tuned pantsulas in finely pressed threads awaiting instruction from their finely menacing general.

What follows next is Mafred, courtesy of Masemola, delivering an ancestral wrenching monologue wrought from the depths. On the screen his address is aimed at his troops, but beyond the screen, it is a cultural lament of the appropriators, the wolves in sheep’s clothing – 1652s who call South Africa’s soul their own.

Mafred cries:

“We, stay together! We fight for what’s ours. They can copy us, and sell the fake to us. But they’ll never get to the depth of our souls. No matter how much they try to make us irrelevant, they can never be us! To be us is hard, you have to lose the privilege the world has allowed you.

Even those who are supposed to be our protectors, our guardian angels against our enemies, we know they too fight us. They know, we know, we are gifted. We know they fear us. We fear them too, but we never gonna give in the fight for our existence. We have our stories to tell, and a history to write!

TJOVITJO!!! TJOVITJO!!! TJOVITJO!!!”

Sheeed, it is no longer business as usual on the small screen.

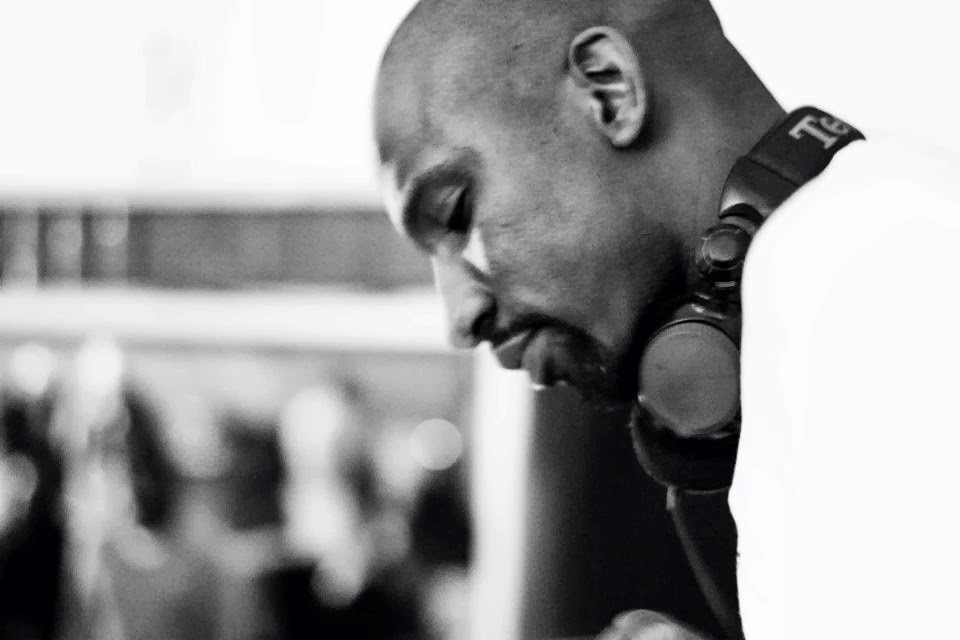

Vincent Moloi (Director) on Tjovito

This story matters to me because I can see myself in it. We have experienced hardship in the cruelest way you can imagine. So I wanted to tell a story that black people are familiar with and I wanted to make it a Kung-Fu and Western style story because I remember mapantsula as being extremely organised when they battle with their nice shirts, nice ironed Dickies trousers, and All Stars – but at the same time they were going to war.

Sometimes on television we don’t get to the depth of our stories because we put gloss over it and end up with unrealistic fantasies. So in this instance we chose to confront and face the truth to better prepare for the future.Tjovitjo is an attempt to bring reality to your face in a way that you can’t avoid it. We are swimming against the tide and trends of South African television. We wanted to represent a part of life that doesn’t exist currently on television. It might work against us but it is part of our responsibility as artists to tell it as it is, although it is highly stylised and dramatized.

I don’t think there is a show on TV that will give is’pantsula the platform to sell itself than Tjovitjo will. We didn’t turn actors into dancers, but we spent over a year turning pantsula dancers into actors. And it’s no coincidence that every member of this production is black. The cast and crew were in tune with the project from the beginning and were often singing the songs and replicating the dance moves in between takes which made for a very jovial set. A black and proud set.

On Representing Pantsula Culture

Black culture is not as recognisable or as acknowledged as other cultures. It has always been seen as inferior and unfortunately due to our history and the elite – the people who control culture in terms of what’s good and what’s not, don’t understand what we are about. Outsiders often lack the emotional appreciation because they don’t have the lived experiences and no comprehension of its roots.

I hope that our efforts and energy will be reflected on screen. I think Tjovitjo is one of the realest township stories that has ever been told. It’s not based in Soweto, it’s not based in Alex, and it’s not based in any specific township. It’s based in a world where there is hardship, hopes, dreams and problems. It is about us and our lives.

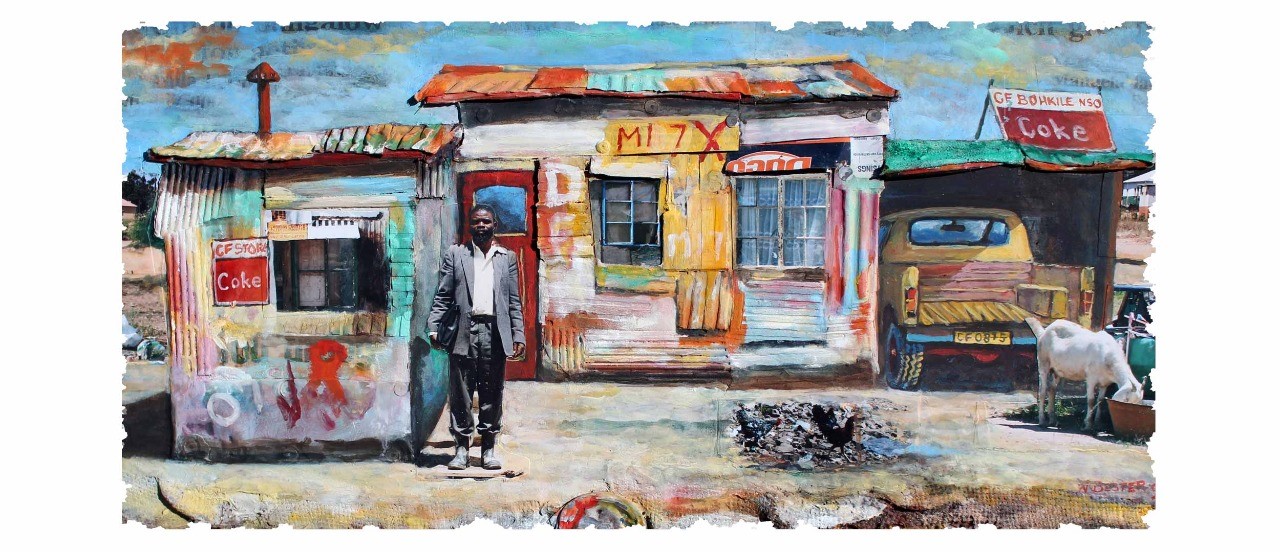

The Location – Nongoloza and the Crown Mines

While the setting of Tjovitjo is not recognised as the Crown Mines where it is shot, it is ironic that the world of the story is located at an area where one notorious Nongoloza Mathebula, (he was born Mzuzephi Mathebula) once reigned supreme.

Nongoloza, like amapantsula, organised his crew to fend off an unjust system. Indeed there was a criminal element to his organisation which was called the Ninevites (way before the 26, 27 & 28 prison gangs) in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The mastery involved in putting out inumber inumber today, is akin to the strict adherence to the agreed upon choreography in pantsula dance. Nongoloza’s band of thugs planned their attacks meticulously and initially had a noble cause, but eventually they didn’t discern between the colonialist and the black labourer.

“I reorganised my gang of robbers,” he (Nongoloza) reported to his white captors in 1912. “I laid them under what has since become known as Nineveh law. I read in the Bible about the great state Nineveh which rebelled against the Lord and I selected that name for my gang as rebels against the Government’s laws.” – Johnny Steinberg; Nongoloza’s Children: Western Cape prison gangs during and after apartheid.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that Nongoloza’s ghost still lurks in these parts. Perhaps it is the migrants and immigrants who tread these paths at dusk after a day of dusty labour at the surrounding warrens that hide precious metals. Walking from the set to base camp requires caution, but after a few trips, one acquires a pantsula motion in his step that may confuse even the most ruthless of Nongoloza’s lieutenants.

And as Idah Makukula in Amapantsula Identities in Duduza From the 1970s to Present Day portends, the pantsula’s errant life outside of dance is often in response to the violence of poverty unleashed upon them by the system.

Crown Mines today is still a scene of poverty and squalor. And so an element of criminality informs a significant layer of Tjovitjo’s storyline that encompasses the narrative of amapantsula over the decades – a compound of charisma, artistry, brotherhood, violence and survival.

*Watch Tjovitjo every Sunday at 8pm on SABC 1.