PART I

Simon says our screams become songs, and our songs become a gateway through which we see ourselves as is, or as becoming. He says we must sing, paint and write ourselves to freedom, however and whichever way we imagine it. But Unathi Slasha says they will slit our tongues and our shouts will sink, syncopate. How then do I sing these songs of fire that erupt inside of me? To whom do I make confessions about my visions of better tomorrow(s)? No doubt our tomorrows are not guaranteed; possibly the only guarantee is that of condemnation. But do I stop screaming, trying to find new ways of being and styles of breathing? I cannot stop, for I know that the embers that burn inside me shall never die. So I continue to write, to document and to archive – because however gruesome our current conditions, our experiences still matter.

It is not clear how I became a writer. There was no definitive moment. Growing up, I would journal, and also had stints trying rap and poetry. After all, where I come from there were no writers. The books we read were Benny and Betty in primary school and Animal Farm in high school. But perhaps my preoccupation with my mothers’ Drum and True Love magazines was a sign of the affinity I had for the written word. I managed, out of the many who could not, to get into university – and the obvious choice was Law. The profession was and still is synonymous with ‘success’. When I told my mother that I had been accepted to Law School, she was convinced that I was going to take her out of poverty immediately, and our family would soon live like the ones we watched on television. Little did she know that the opposite was going to happen… That I was going to plunge her and myself into debt and end up not becoming a lawyer.

The reason was simple. Throughout Law School, I wanted to do nothing but write stories of the imagination and retell tales of yesterday. It was what gave me life when all the statutes and court judgements I had to read were squeezing all the life out of me. It is then that I realised that there was no way I was going to be a lawyer. I also did not want to be a writer, because all the writers that I had gone on to read about had led miserable lives and were drunkards, druggies and abusive. So it was a conundrum, but regardless; I continued writing. When I graduated from Law School, I went on to study Creative Writing; just to buy time. There was no way I was going to join corporate South Africa – the Steve Biko bug had bitten and I was conscious of the evils of capitalism. I have since been writing, broke, surviving. And not dying, just because I am writing.

PART II

To be an artist means many things at the same time. It is not something that one just decides to wake up in the morning and do. That is why most say it’s a calling. Callings are important because in most cases they mean one has a duty towards society; a duty of finding ways to make it better. Take music and literature for instance – there is no doubt that these art forms have played an important role in our societies as mediums that were able to articulate the collective concerns of the people. The struggle against apartheid, for instance, is unimaginable without the role that song played. The civil rights campaigns cannot be thought of outside the literature of that time. That being said, callings can also mean an inescapable burden placed upon the called. To be an artist means there are many sacrifices that one has to make. One sacrifice that is almost always guaranteed, in many cases, is that life becomes miserable – quite often because it is difficult for artists to make a decent living from their craft.

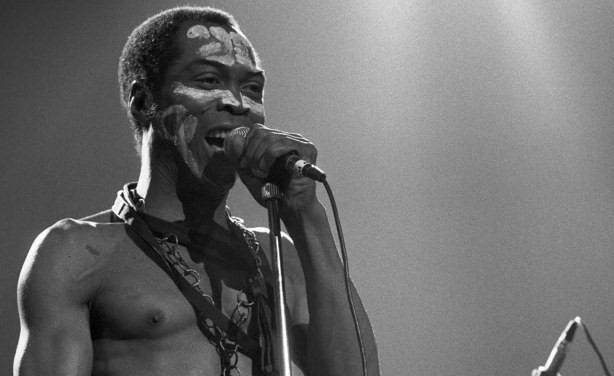

What is most painful is that these sacrifices are much more immediate when you are a Black person, quite simply because of the history/present of racial oppression in South Africa. During apartheid it was hard being a Black artist, as it is even now. Artists back then were censored, arrested and even exiled. In the present our voices are still constricted. There are certain things we cannot afford to say, especially if we want to get access to some platform or the other. Black people cannot create artworks with total artistic freedom, because there are no trust funds for us to fall back on; what we do has to give us bread. There are certain spaces that we cannot access because we do not fit the category of ‘acceptable Black’. Behaviour, demeanor, accent and the subject matter you choose – all these play a role in who will pay you as a Black artist. The intrinsic artistic worth of your work is rarely considered.

So the cookie then crumbles in two possible ways. If you want to be a rich artist, the quality of the work has to be compromised. The work has to bend to the demands of the industry or establishment. Of course there are exceptions, but this is often the case. For the work to be exhibited in galleries and be subsequently bought, it must appeal to a particular market. The same goes for other art forms such as film, literature and even music. This is how artists are censored, restricted and limited in the ways in which they produce work. So the big question is what is to be done? A very difficult question, for various reasons. In the first instance, it is because we exist in a highly capitalistic society where everything is commodified. Where things are sold, not on the basis of the societal value they bring, but rather because of how much super profits they can generate. Another problem is that art is often treated as a hobby; even the ways in which our government treats art corroborates this. Its social value is completely undermined, so much so that it is not considered as work proper. Companies refuse to pay artists what they are worth, and that’s if they even decide to pay.

PART III

8 notes for the artists who have had to struggle just to be able to afford bread.

1.continue creating, the work you make is much more important than what you’ve been deliberately made to believe.

2.connect with other creators, be inquisitive and curious.

3.things will get better with time, and if they do not, create art about that.

4.pester these companies to process the invoice; like a doctor, nurse or garbage man you deserve to be paid on time.

5.when the invoice eventually gets processed, budget; spend that money wisely because these gigs are seasonal.

6.be dependable and reliable, bad reputation has cost a great number of talented artists many opportunities.

7.drink water and avoid drugs, your work should be your work.

8.organize with other artists, create institutions, and build.

PART IV

One ought to remember that as artists we are not static. We are not inert creators but we are always expressing in motion, oscillating between history and the present – trying to forge a future. I have hope that things will not remain this way. That we will find solutions that make it better to exist as artists in a world such as ours. Let us look to the past and find which lessons we can draw from it, to try and navigate life better as artists. But when all is said and done, let us continue to create. The world needs us, and without us will bleed out of existence.

Copyright: Cav’ Platform / Goethe-Institut Südafrika

Cav - Goethe