the blues is how we live this jazz is how we speak there is life in this swing we have suffered long enough to know for sure this getting happing aint simple stuff

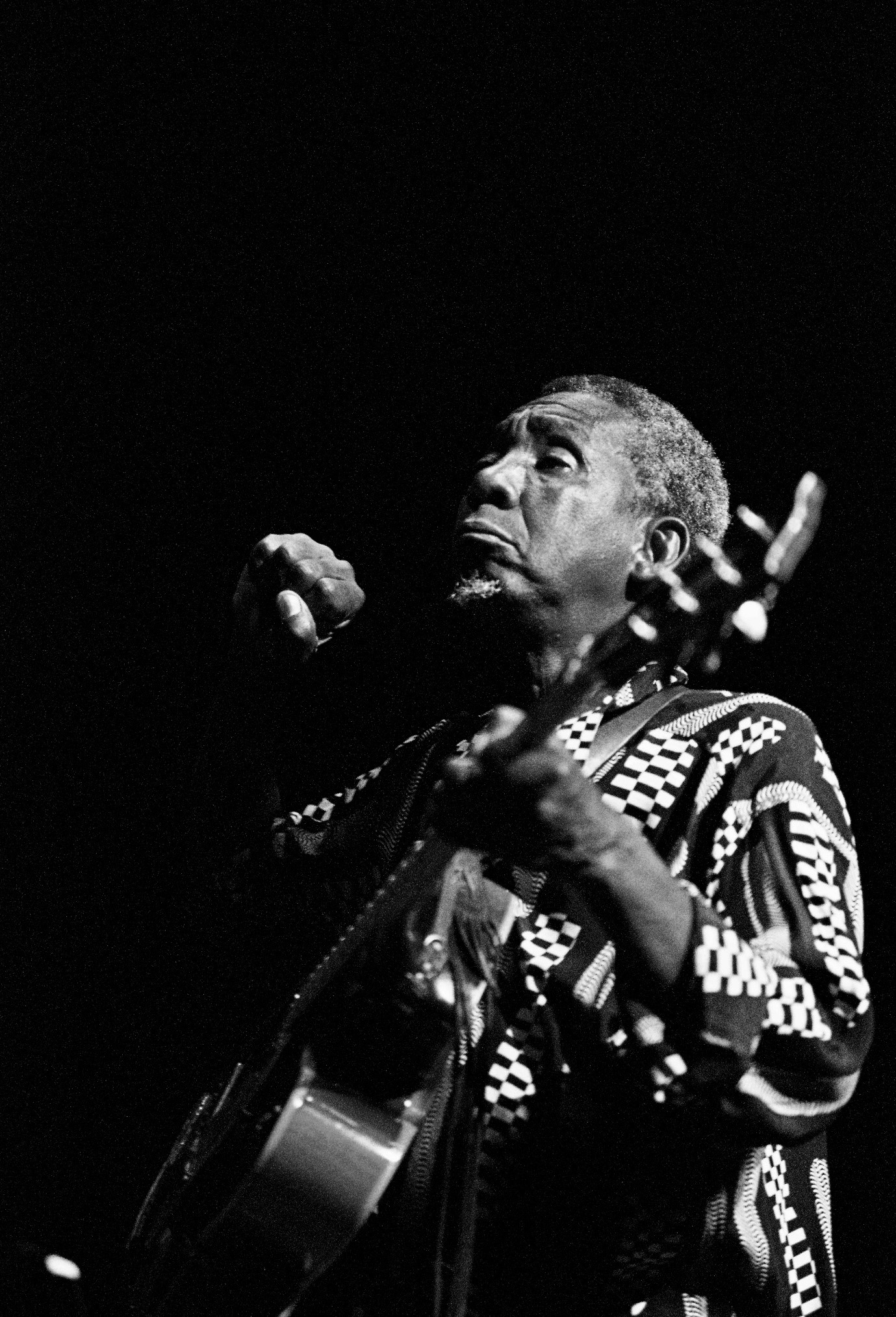

The extract above is from Mphutlane wa Bofelo’s poem, This Blues is Us: Ke Kgale re Tshwenyeha. The poem is dedicated to Phillip Nchipi Tabane and was inspired by the lyrics from his song, Ke Kgale re Tshwenyeha. In the song, Tabane bellows:

ha le re bona re le pelo-thlomohi

le re tshwarele.

ke kgale re tshwenyeha

A loose translation of the meaning of Tabane’s holler or chant in English is:

pardon us when you see us

feeling blue all the time (looking heartbroken)

for too long we have endured suffering and agony

Tabane’s holler and Bofelo’s poetic weeping echoes Fhazel Johannesse’s poetic declaration: “Black pain and sorrow are one” and resonates with Terrence Blanchard’s proclamation:

“What makes jazz African American for me is the pain and suffering, the honesty about our search for truth, making it more than purely a musical style.”

Indeed, the Malombo howling reverberates with the expressive singing and entrancing harmonies of Billie Holiday, translating the instrumental improvisation in jazz vocally with an alteration and variation of melodies to express pain, joy and heartbreak, and articulate the agonies and ecstasies of being Black in the world:

Southern trees bear strange fruit, Blood on the leaves and blood at the root, Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar tree, Pastoral scene of the gallant south, The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth, Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh, Then the sudden smell of burning flesh. (from Strange Fruit, Billie Holiday. 1954)

It resounds the harrowing cries of the Black Consciousness induced children of 1976:

Basibulala ngengezinja. Siyenzeni na? sonozethu ubumnyama”

(They kill us like dogs. What have we done? Our sin is our blackness.)

This song of the children of Black Power is almost a translation of Louis Armstrong’s lyrics in (What Did I do to Be So) Black and Blue:

My only sin Is in my skin What did I do To be so Black and Blue

The permeating theme of the ontological death of Black people under slavery, colonialism, racism and apartheid-capitalism and their efforts to lift themselves above deadness through song, rhythm, beat, melody and dance, underscores the undertones of Black Existentialism (Black Consciousness). This is present in jazz and the poetry of Black people who are conscious of the reality of being Black in the world. The relationship between jazz and Black Consciousness is forced by the historical and material realities that gave birth to jazz and Black Consciousness.

Emergence of Conscious Jazz

Jazz and Black Consciousness both emerged out of efforts of Black people to find their own voice in an anti-Black world that denies Black people a sense of being and belonging that is at variance with the stereotypical portrayal of Black people as subhuman and inferior beings who are incapable of making and developing any refined and distinguished philosophy, science, art and culture outside the proprieties, protocols, conventions, canons, and orthodoxies of Eurocentrism and outside the regimes and regiments of White Supremacism.

Both turned around concepts that in the sociological imagination and political language of White supremacism denoted primitiveness and backwardness and used them to articulate the desire and efforts of Black people to assert and exert themselves above the dehumanisation, alienation and estrangement they suffer in an anti-Black world that is dominated by the regimes and regiments of racial and class oppression.

Both emerged outside the mainstream — as essentially anti-establishment projects — but now contend with efforts of the establishment to recruit and contain them within the straightjackets of the mainstream to sap them of their avant-garde anti-establishment ethos. Both provided a political outlet for Black people to provide a counter-narrative and counter-culture to eurocentrism and western hegemony.

The Western Myth of Blackness

To understand these shared attributes of Jazz and Black Consciousness, it is important to briefly summarise the portrayal of Black people in Western philosophy and culture and the way the white world received the advent of Jazz and Black Consciousness.

Mainstream Western philosophy has for centuries thrived on the idea that only the White Caucasian race was capable of culture, art, science and philosophy in the true sense of the word. Accordingly, Western philosophy contrived African ways of living and of doing things as all mumbo-jumbo. As a result, Western philosophy lumped the beliefs, knowledges, practices, rites, ceremonies and aesthetic, artistic and cultural expressions of African people under the header of voodooism, though the word or concept called voodoo does not exist in any of the African languages.

This negative perception of Black people is informed by the fact that European civilization was rationalised through a rank ordering of races. In the arena of philosophy, this finds expression in David Hume’s philosophical suppositions about the natural inferiority of negroes. Immanuel Kant endorsed Hume’s philosophical rationalisation of racism and developed his own theory on inferiority and superior race types.

Subsequently, generations of Europeans and Euro-American White people have been educated and trained to accept and embody widely shared common senses of their racial superiority as reasoned and sanctioned by supposedly philosophically well-reasoned, science verified and theologically sanctioned teachings.

Consequently, for centuries, Western philosophers were obsessed with the question of whether Bantu was sufficiently philosophical to be capable of philosophising and producing a philosophy and civilization in comparison to the European White Man.

Even philosophers operating within the framework of dialectic and historical materialism, such as Frederick Engels and Karl Marx, portrayed Black of African origin as incapable of a civilization and culture before their encounter with the West. The refusal to associate Africa with philosophical, scientific, and technological innovations informs the sociological imagination of Europe and the USA that deliberately locate Egypt in the Middle-East to discount any link between Africans and the Egyptian civilization.

The view that Black people of South Saharan Africa, the Bantu, are incapable of a philosophy and a culture was partially unsettled by Placid Temple’s book La Philosophie Bantoue (Bantu Philosophy), published in 1954. This book by Temple, a Belgian priest, claimed that Bantu People had an indigenous philosophy, thereby challenging the dominant racist imagination and thinking about the intellectual and social capacities of Black people.

However, Temple’s work did not move completely outside the Western European White Racist imagination. Temple claimed that the Bantu were incapable of being conscious of their philosophy. He asserted that he, because of being a white man trained in philosophy and capable of engaging in hermeneutics, was able to extract the constitutive and axiology structuring behaviour guiding philosophy at work in the linguistic and normative action of the Bantu people.

Still Temple’s Bantu Philosophy had tremendous impact in challenging the view that Africans were incapable of producing a philosophy. It shifted the focus from Philosophical debates to whether Africans can produce a philosophy to whether or not there were proper philosophy in pre-colonial, Sub-Saharan Africa.

From Negro Spirituals to Commercial Jazz

It is within this context that we must understand the efforts of the European enslavers to completely cut off the African people from their language, culture and heritage and the brutal violence unleashed on enslaved African people who were found speaking their ancestral languages or indulging in African music, dances, rites and ceremonies that express their African being and their sense of belonging to Africa.

The enslavers correctly interpreted the African work-songs, field-hollers, shout and chants as a struggle of memory against forgetting, a resilient act of refusing to be entirely alienated from the continent of origin and the self and a rebellion against complete assimilation into the enslaving culture. The African people responded to attempts to throttle their aesthetic and cultural expression of social reality, their yearning for freedom and their longing to return to Africa by hiding their liberation songs in the musical elements of the religion of the enslavers, namely Christian hymns.

This took the form of the so-named negro spirituals. Before long these musical elements gave birth to the blues and later jazz, drawing mostly from the music of Western Africa distinguished by improvisation, call and response lyrics and polyrhythms even as utilised, in a limited way, European forms of harmony and structure.

According to musicologists, such as Gunther Schuller and Lee Evans, an analytic study of jazz reveals that the basic forms and musical elements of jazz from harmony, melody, and timbre (i.e polyrhythms, syncopation, call and response, repetitiveness, blue notes, open tone and natural quality, individuality, collective improvisation and portamento) are essentially African in background.

In the same way that music form found its pulsation outside of classical music of White America. While there is a belief that the term jazz is derivative of the slang word, dating back to the 1800s, jasm, meaning “verve or energy”, the first recorded use of the words was in derogatory manner in 1912 when the Los Angeles Times quoted a baseball player referring to a pitch as a “jazz ball” because, in his words, “It was wobbles and you simply cannot do anything with it.”

Similarly, in the arena of music, the Times-Picayune of 14 November 1916 made reference to the “jas bands”, which is derived from the slang word “jass”, meaning “dirty or bad”. It is no wonder that initially White mainstream commentators and art critics regarded jazz as inferior in the same way that the record labels and white audiences regarded jazz as a lower music form because of its association with Black culture.

Nina Simone was referring to this attitude when she asserted: “To most White people, jazz means black and jazz means dirt, and that’s not what I play. I play Black classical music.”

When they finally latched on to jazz for commercial reasons, mainstream record labels sought to make it acceptable to the white middle class by parachuting average white jazz players to stardom above equally and even more talented Black jazz artists. In this regard, Lee Evans provides the example of Benny Goodman whom the American media crowned “king of swing”, making him famous and rich while extraordinarily gifted Black swing jazz artists struggled.

Jazz, as Rebellion and Resistance

Attempts to find white figureheads of jazz and contain the highly emotive, explosive, volatile and stirring ethos of jazz within the sobrieties and proprieties of western harmonies and structure were informed by the realization that jazz was quickly becoming the register and podium of Black pride and Black rebellion against the jackboots of White supremacism. A clear example of potency of jazz and Black music in general as political platform and a weapon of liberation is Charlie Mingus’s blatant and fearless attack of Jim Crow attitudes:

Oh lord don’t let them shoot us!

Of lord don’t let them stab us!

Oh lord don’t let them tar and feather us!

Oh lord , no more swastikas!

Oh lord , no more Ku Klux Klan!

Name me someone who’s ridiculous, Danny

Governor Faubus!

Why is he so sick and ridiculous?

He won’t permit integrated schools

Then he’s a fool! oh boo

Boo! Ku Klux Klan

(with your Jim Crow plan)

(From Fables of Faubus, Charlie Mingus)

This song could be described as revolutionary theology in lyrics, positioning God on the side of the oppressed, openly calling out the devil that runs havoc on Black people’s life by name. Similarly, when the Black Consciousness Movement emerged in South Africa (Azania) in the late 1960s, it saw the importance of rebelling against the language, symbolism and reasoning of White Supremacism to create the language and culture of liberation based on self-redefinition and a redefinition of the terms and terrain of engagement, conceptual, theoretic and theological frame of reference, and aesthetic, artistic and cultural expression of social reality.

Therefore, the BCM’S point of entry was to rally the victims of slavery, imperialism, settler-colonialism, racial-capitalism and neo-colonialism around the very Blackness based on which they are othered, objectified and denigrated to turn Black into a socio-political self- identity around which to build the solidarity of those at the receiving end of settler-colonialism and racial-capitalism and the racial hierarchies it established.

In this way, Black Consciousness confronts the problematisation of Blackness or the apartheid notion of ‘the Black problem’ by exposing the fact that the real problem is anti-Black racism which is abetted and sanctioned by the regimes and regiments of racial-capitalism.

Right from its inception, the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa (Azania) emphasised the importance of reconstituting and marshalling the most positive aspects of Black culture and African knowledge-and-belief systems to free the minds and souls of Black people that they may be free and reclaim their land, dignity, pride and being.

Bantu Steve Biko eloquently expressed the pivotal role of Black music in capturing the communalistic ethos of the African way of life and its potential to be a media of the collective agency of Black people in their struggle to call their souls their own:

“Nothing dramatizes the eagerness of the African to communicate with each other more than their love for song and rhythm. Music in the African culture features in all emotional states. When we go to work, we share the burdens and pleasures of the work we are doing through music.

This particular facet strangely enough filtered through the present day. Tourists always watch with amazement the synchrony of music and action as Africans working at the roadside use their picks and shovels with well-timed precision to the accompaniment of background song. Battle songs were a feature of the long march to war in the olden days.

Girls and boys never played any game without using music and rhythm as its basis. In other words, with Africans, music and rhythm were not luxuries but a part and parcel of our way of communication. Any suffering we experienced was made more real by song and rhythm. There is no doubt that the so-called “negro spirituals” sung by Blacks in the States as they toiled under oppression were indicative of their African heritage.”

It is this keen awareness of the importance of music, dance and theatre that made the BCM provide a platform for music groups and actively encouraged the establishment of music and theatre groups that tap in their African roots and heritage. Poet and visual artist, Lefifi Tladi, who was part of the Dashiki, the group that fused jazz and poetry, recounts:

“Dashiki operated within the structure of Black Consciousness with absolute independence. The BC movement used to book places where we could perform whatever we wanted. That was the best outreach project.”

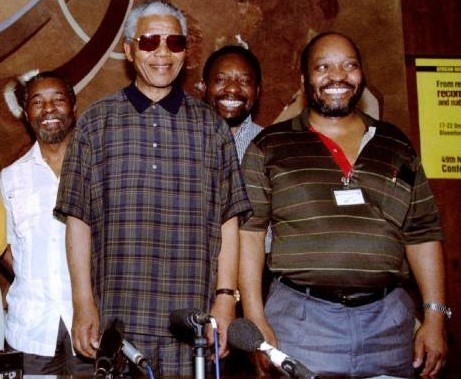

The influence of BC on specifically jazz artists in South Africa (Azania) is illuminated by the recollections of Pops Mohammed that “the impact of Black Consciousness in the early ad mid 70s saw groups such as Dashiki Poets, Malombo and Batsumi articulate a strong Black and proudly African identity”.

The prevailing material conditions made the struggle of jazz artists to make music in the middle of oppression inseparable from the broader struggle for liberation. Hence, the most popular slogan of the 1980s was “The Struggle for Jazz, Jazz for the Struggle”.

The limits that the apartheid laws placed on free movement and various civil liberties and socio-economic rights directly had an impact on musicians. With the establishment of the homelands and Radio Bantu with separate channels for different language groups, the apartheid regime discouraged artists like Babsy Mlangeni, Mpharanyana and the Soul Brothers from using multiple languages in their music, as it sought to pigeon-hole in “ethnic categories”.

Veteran musician, Pops Mohammed states that jazz artists were specifically construed as rebels for their refusal to conform to the straightjackets, the versatility and boundary-crossing nature of their art form and its stirring, fiery and volatile pulsations:

“Choosing to simply be a musician or to play jazz can be read as a political stance. Jazz was seen as a proudly Black articulation of identity, with its heat, the idea of being free. In many ways, this was construed as revolutionary. The struggle was about being someone the government didn’t want you to be, as they tried to straightjacket people into fixed identities and destinies and roles within their social engineering.

As jazz came to represent a form of resistance to the ideology of apartheid, it became more and more difficult for players to find record companies that would record and issue their records, or even to find venues that could afford to keep booking these artists. Choosing to play jazz under apartheid was not a smart financial move but many felt they had no choice at all but play it.”

We Keep Playing On

This is yet another way in which the story of the emergence and evolution of jazz in South Africa (Azania) is similar to that of the emergence and evolution Black Consciousness in the country. In its early days, the apartheid regime erroneously thought that the philosophy of Black Consciousness with its emphasis on the politics of self-identity and group solidarity was not inimical to its separate development policies.

But as soon as the regime saw that its anti-racism stance and its rejection of assimilation, in favour of genuine integration, (that derives from the closure of all doors of prejudice and elimination of all forms of oppression injurious to the agenda of apartheid-capitalism) it went on a full-force attack on Black Consciousness.

It killed its key theorists and activists like Mthuli ka Shezi, Mapetla Mohapi, and Onkgopotse Ramothibi Tiro, and imprisoned and drove others to exile. The regime was joined by the liberal, social democratic, progressive democratic and Marxist-Leninist voices in dismissing Black Consciousness as reverse racism, in campaigning for the non-recognition of the BCM by important continental and international forums, and in the harassment, intimidation and killing of BC activists across the country.

The bold decision by jazz artists to continue making and playing (even as the regime subjected them to restrictions, repression and imprisonment and forced many underground and into exile) is similar to the resolve of Black Consciousness theorists and activists in South Africa (Azania) to continue preaching and practicing Black Consciousness — through various socio-political, cultural and intellectual platforms.

The concerted efforts to de-link Bantu Steve Biko from BC organizations, co-opt gullible BC individuals and organisations into the neo-colonial liberal democratic capitalist project or to dilute Black Consciousness into some intellectual and cultural project rather than a radical philosophy of liberation is akin to the use of the name jazz to promote commercial and populist ventures that have little to do to jazz.

lungs battling iscor flames despite the new leaf arcello mittal claims i come ridding vaal river waves rowing over emfuleni paddling to the vaal bank i hear vaal dam screaming for peace

refengkgotso is not the cry of fishes trapped in a net

but of human souls caught in the poverty trap

shattered bodies find mental solace

in brash dances, cheap beer and cut-rate spirits

acid from car-batteries add spunk to homebred brew

brothers and sisters drown their sorrows in jazz by the river

but don’t tell them about Mackay Davashe, Chris McGregor & Thelma Segone

these revellers think Coltrane was a train-driver

Nina Simone a madam from the Midvaal

still to the rhythm & blues they swing their hips

the smart boys the cool cats ululate to the symphony of black bodies

with chants of “ check daai ding…hoor net daar!”

a mantra that says: this dog is into jazz

just don’t ask big buddy the man-about-town

what Marsalis said jazz is and is not

don’t bother the sharp man with bookish homilies and arguments

between proponents of fusion and protagonists of unadulterated jazz

or where the hell Miles’ improvisation,

versatility & spontaneity fit in in the whole debate

mister and madam new rich don’t need restless minds

the fiddle class cannot afford unrest

they just want to relax without stress

take a rest at Abrahamsrus

any excuse to shake that ass

even in the name of jazz

play it philanthropic and dedicate the carnival

to the lost fight against HIV & AIDS

at the end of the day it makes logic

to say it really is a massive act of social responsibility

just to offer the masses the comic relief

of a momentary escape from the ghettos & bundus

of Fezile Dabi:

Moqhaka

Ngwathe

Metsimaholo

Mafube

the labour camps; backyards & scrapyards

of lily suburbs, white farms and wage slavery plantations

sasol

lonmin

aurora

anglo-american corporations

the sweatshops & warrens of unbridled

accumulation of capital & shameless commodification of life