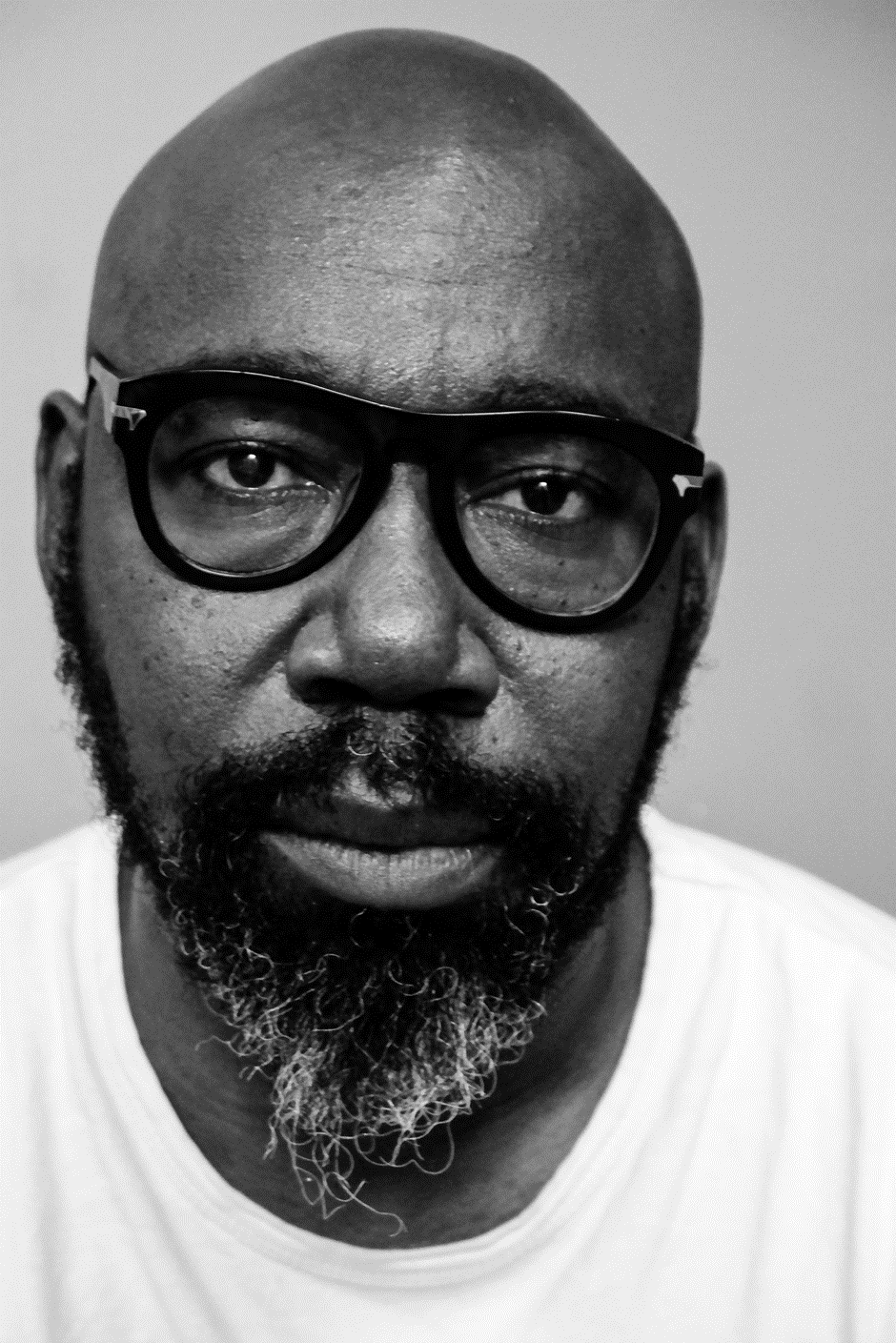

Moses Taiwa Molelekwa. The keys you created with your fingers take me back to the day you are found dead. Hanged. And your wife strangled to death. You are both lifeless with your wife/manager, Florence, in your office in downtown Johannesburg. A day before Valentine's Day. Was it a crime of passion, perhaps? Or just cold blooded murder targeted at Jozi’s power couple? So many questions fill my head. What happened to the life of this young music genius?

It's twenty years now since you are gone.

That fateful day saw you mysteriously ushering yourself into the 'Darkness Pass' – also the name of your last album. The idea of the ‘darkness pass’ reminds me of an ancient Greek musician, Orpheus, that the French writer, Maurice Blanchot, philosophises about.

Orpheus is a musician in love with his Eurydice, indeed a muse. But he is an aggrieved lyre player whose wife dies and leaves him melancholic and devastated. He then desires to follow Eurydice to the underworld. And Blanchot is of the view that 'when Orpheus descends to Eurydice, art is the power by which night opens'. Although the supreme art is enacted by this immense darkness, there is a price to pay. For Orpheus is, as a music genius, capable of approaching the night 'except the centre of night in the night' because it is that which annihilates him. It’s precisely through this kind of sacrifice of a life that the ultimate artwork shall see the day.

And the gesture of this gift is the posthumously released album, Darkness Pass (2004), as though attempting to narrate your journey to the underworld. Solo piano pieces communicate your story in the fashion of a monologue. They are meditative and soothing keys as though you are making peace with a particular truth about life. The whole album taps into classical jazz in the international sense without losing its locatedness in Afrika; transposing the indigenous sounds like imbira, kora, uhadi, into your piano. Notably, 'Darkness Pass 3' is elegant with a light touch, evoking feelings of relaxation like 'Darkness Pass 8'.

I see you, Taiwa, passing through such darkness and never coming back. Such great pieces of music inaugurate your death. Blanchot knows this clearly; you cannot achieve the furthest, the ideal, point that art can reach and still live to witness it. The keyword here is transcendence. However, that point has both aesthetic rewards and dire consequences, since it ironically announces the death of the artist, both literally and symbolically. By death, I'm also referring to what George Bataille, Blachot's predecessor, calls eroticism: the spiritual bliss that one enters; much more like an orgasm, a transcendental mode when one forsakes all that is worldly.

Precisely like you, Orpheus dies for this accomplishment.

The album, Finding One's Self (1994), is almost self-evident that it’s your first offering if one looks closely at its title. The songs show a serious pianist who is trying to carve his path. Songs like 'Nomkhosi', the opening number. It’s refined keys and recognizably contemporary jazz. It sets the tone and the mission of the whole album. Blues influenced, no doubt. Here, you are engraving your name among the great names of African jazz.

I like the tenderness of 'Nobuhle'. It's melancholic. Sad. And meditative. However, its beauty is not devoid of the influences of your musical forebears. I’m thinking particularly of Bheki Mseleku's 'The Age of Inner Knowing'. Poised and sophisticated melodies. Maybe 'Nobuhle', she who is beautiful, is a metaphor for a lady whose beauty you deeply admired. Or maybe a muse that one day you would marry and die for. That's what I love about speculative thinking: the boundless possibilities of meaning!

The second offering, Genes and Spirits (2000), is almost busy, fusing jazz with reggae; especially the song, 'Tsala'. I want to imagine the life of a twenty-seven-year-old established jazz musician in Jo'burg. Stoned with friends at the studio and trying to make music. 'The Spirits of Tembisa' is restless and violent like a township life at times. The song dramatises a troubled soul; perhaps, you thought you were only giving a musical interpretation of Tembisa but the song also gives us glimpses into your interior life. It speaks of visceral communication in significant ways.

Not a single day passes without me thinking that you were haunted by the ghosts of Sophiatown (and Harlem). The echoes of their blues possessing you like spirits as you carried on with this noble music genre. Shadows of kwela almost overwhelming as you weave each masterpiece.

I touch the texture and the layers of your melodies, allowing myself to plunge into nostalgia. I am a child who was fed this kind of music in a shebeen home in some township close to your hero's home: Steve Biko. Maybe I was conceived while the LP record of jazz was playing from the Omega hi-fi. I would in turn bathe the patrons of our reservoir with the same music. I insert a ballpoint pen inside the eyes of Finding One's Self cassette to repeat the song, 'Nomkhosi'. I would later understand through your contribution to Kwaito and your mysterious death – as publicised in the newspapers. When Sello K. Duiker took his life, images of your tragic end flickered. He is a novelist whose work you would have loved; extremely talented. I think you were cut from the same fabric.

I like your song for Biko; it is upbeat and mimicking energetic life and youthfulness. Johnny Dyani has an album of the same title, dating back to 1978. You must have loved his quartet. Your song speaks to the liveliness and the resilience of the idea of black consciousness over time. Like many Moses of this country, you tried to transport your people to the Promised Land albeit spiritually.

Another genius who was in your band made a beautiful and powerful song, paying homage to you. Five years after your departure, he was reported to have hanged himself. His name is Moses Khumalo, a saxophonist.

Taiwa, our African Orpheus. I hope you did not strangle your wife for infidelity or any other reason and then took your life to follow your own Eurydice, I would be deeply hurt. I want to remember you as a saint who was sent by African gods.

Taiwa, robala ka kgotso!