In 1994, the air in South African townships was different. Even through dense grey smoke from Gogo’s Magic or Welcome Dover iron coal stove, it still felt and smelt renewed. Hope was abound in every corner; whether littered by ‘VIVA ANC’ graffiti or not. Townships oozed pride and a joy so inexplicable it had to be the lived experience for it to be understood. In the midst of it all, a sound not yet identified frequented unlicensed drinking establishments and ‘6 to 6’ jamborees, wildly commoving revellers. It was Kwaito music. It had arrived. Remember Arthur Mafokate’s Amagents Ayaphanda (1994) and Kaffir (1995)? How about Brothers of Peace’s Traffic Cop (1995)?

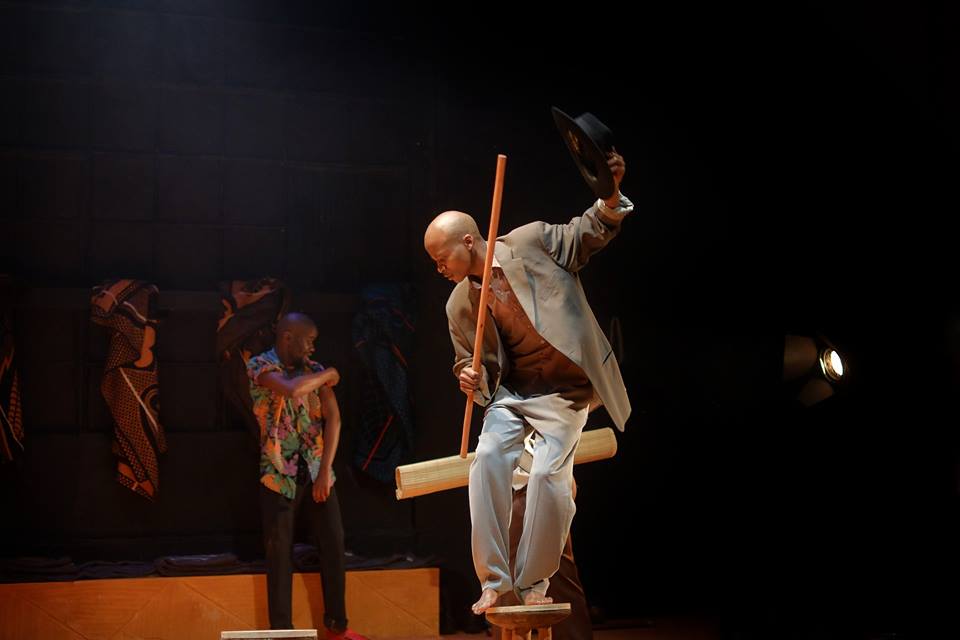

A production beautifully titled Ekasi Lam – An Ode to Kwaito, Un-Owed to Kwaito, from the hand and direction of esteemed writer and director Jefferson ‘J. Bobs’ Tshabalala, looked set to invoke these generational memories and associated emotions as it launched its six-person ensemble into a beautiful story telling frenzy with TKZee Family’s explosive Izinja Zam, to the audience’s delight. With such a title and opening, audience spirits were noticeably high and expectations abound. There is after all, no room for disappointment where Kwaito is concerned. It is an iconic genre credited with having changed many a life, chiefly the South African socio-cultural and linguistic landscape. South Africans from all walks and enthusiasts alike have borne witness to Isipantsula, tsotsi and other concomitant subcultures reinventing themselves on account of this genre. It is this very same fervour and passion that roamed the theatre hall as the showcase kicked off.

Set in an awkwardly named high school in Soweto and unrelentingly sound tracked by Izinja Zam, the show trails the conjoined lives of Ms Feni, the school’s former pupil and now spirited and skilful teacher; her four stirred and incisive learners with a penchant for subculture specific music, dance and Iscamtho; and Dr Tlale the conflicted school’s principal. The audience is introduced to Ms Feni and the learners planning to stage a school concert that uses Iscamtho poetry to celebrate Kwaito as a black, township story-telling genre; its custodians; and Iscamtho itself as the genre’s medium. As the learners and the audience excitedly imagine the staging of a lively showcase reminiscent of days yonder, Ms Feni’s unconventional operation on the fringes takes centre stage and prescribes an oratory instead, void of performance or music; a rude turning point not only for the concert itself but for Tshabalala’s production similarly. The succeeding hour of the showcase sees the five characters proceeding to explore concert ideas in depth and unceremoniously thrusting the audience into a mind-numbing roller coaster of long-winded and preachy monologues masked as multiple exchanges, thus truly defining the showcase as an anti-musical. The brilliant cast does best to carry the showcase despite its visibly draining nature but evidently struggles as it is also mired by the disconnected and ineffective transitions that end up seeming like an attempt to break and regroup in place of bridging to new scenes. The incessant delivery of Izinja Zam at every turn at the hands of musical director Bernett Mulungo also defeated the purpose of his role in the production as it stifled the very wild and free nature of Kwaito. It in effect denied the audience a proper tour down memory lane with a vast sample of the genre’s greatest hits.

While Tshabalala’s conceptual direction cannot be faulted given the content of this showcase, his ability was nevertheless compromised. Commendable for an attempt to stage what had the potential of being a monumental showcase and the only of its kind in this climate, it is perhaps necessary too, to point out that the brilliant Tshabalala bit more than he could chew on this here production. There just was too much unrelated content that ruined what could have otherwise been a decent showing. The production thus leaves a bitter taste in one’s mouth and perhaps could be likened to an almost sneeze as it failed to excite beyond its first 20 minutes as suggested by its striking and apposite poster; and synopsis.

Having done well to explore the immensity and dynamism of Iscamtho to sociolinguists’ enjoyment, Ekasi Lam – An Ode to Kwaito, Un-Owed to Kwaito has not however delivered the promise of its title to its nostalgic audience. The showcase could certainly do with a rewrite to do right by this iconic genre and its generation of writers, singers, performers and listeners alike. Tshabalala may have to consider releasing the ‘street bash’ and ‘6 to 6’ soirée beasts evidently detained in his brilliant cast and allow for a proper celebration of Kwaito in its truest form, perhaps the last ever ‘bash’ of its kind.

‘Ekasi Lam – An Ode to Kwaito, Un-Owed to Kwaito’ is currently showing at the Market Theatre until Sunday, 08th September 2019. Tickets are available at a lowly R90 through Webtickets.

Twitter: @skrufu

Enter your email address below to subscribe to my newsletter

-

Sampa The Great - Jozi

-

Amanzi

-

Kelenosi

-

Soothsayers & Masters of Perfect Timing

-

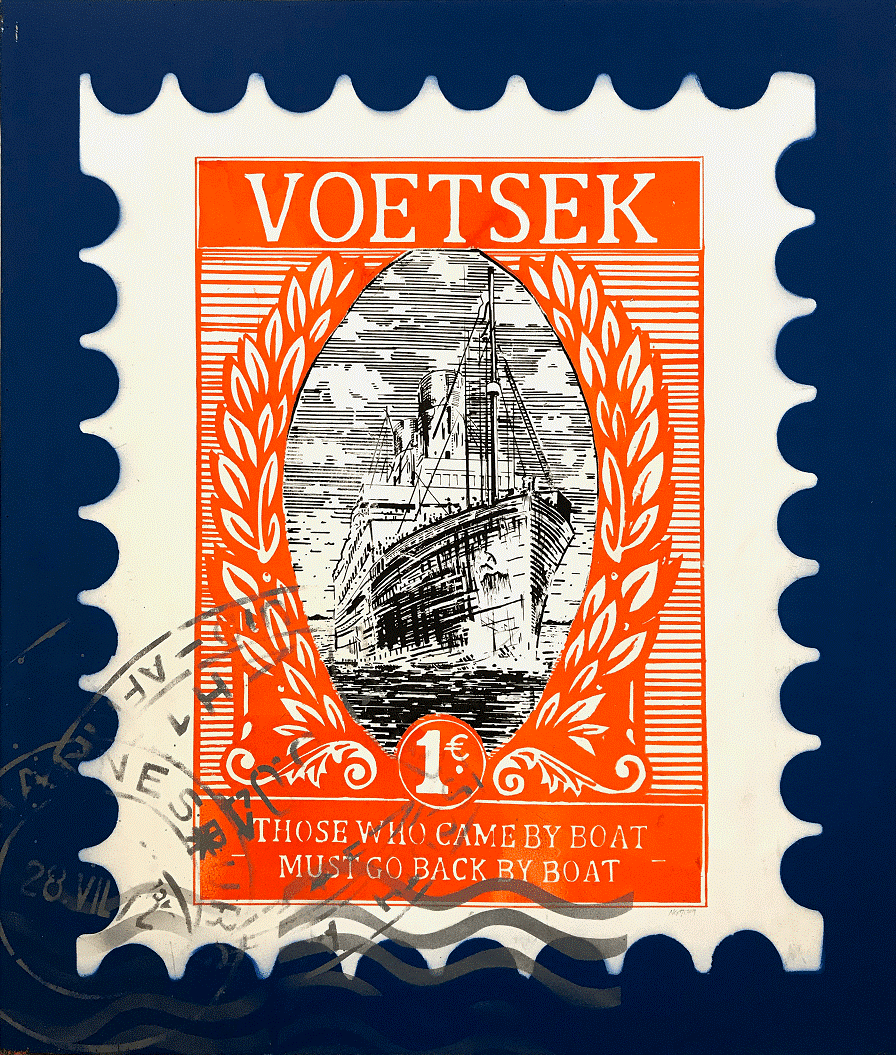

Between The Devil & The Deep Blue Sea: Qua Vadis, South Africa

-

Azania’s Time of Trouble: The Coming of The Europeans and Racial Capitalism

-

Turbulent Relationship Between Russia and Ukraine

-

REVIEW: Pulitzer Award Winning Play, RUINED

![1976 [Part2]](assets/images/1976.jpg)