1

Even before you are born, the path of your life has already been mapped. It goes on and on and then it turns on itself and goes into a loop. There are days when you feel dizzy from travelling around in circles.

On some days, it feels like foreign objects have been placed on your path for no other reason than to inconvenience you. You do not notice the first thousand tumbles. You dismiss the dirt on your clothes as the residue of nightmares you cannot fully recall.

The lump in your throat, it must be from the nightmare. A chant you cannot remember singing. You begin to feel exhausted. It becomes clear that the world is not kind to a dark-skinned and poor person. You have tried it. This thing of being positive, seeing the silver lining; except sometimes, there is no silver lining in sight.

2.

This is how black tax begins … It doesn’t start when you are much older and have a job, with endless siblings to support and ageing parents who have no pension whom you must look after. No, it already begins to eat at you at the mall when your father tells you the sneakers you want are too expensive to buy. You are twelve. You stare at him in disappointment and then you stare at the sneakers again. You can hear them call your name.

From that day, you make a promise to yourself that, for the sake of your wellbeing, you will suppress your desires. You also naively make the promise that when you are older and more successful than your dad – which you will be, you promise yourself – you will buy yourself all the sneakers in the world.

It does not occur to you at that moment in the store, when you notice the absence of meat at dinner or when you are told you can’t attend the school’s outing because there is no money, that this is the path your life will take for the remainder of your days on this earth. That you will come to know these shortcomings intimately, like one comes to know the limits of their own love.

Throughout your childhood, there are the glimpses of another life, an alternative universe, where you are sitting in a mansion, perhaps floating in a jacuzzi, driving down a highway, air blowing through your thick hair, and you are wearing the sneakers your parents could not afford to get you. Depending on what day it is, these glimpses are more or less frequent. They are always a distraction that rescues you from the abyss you are destined for.

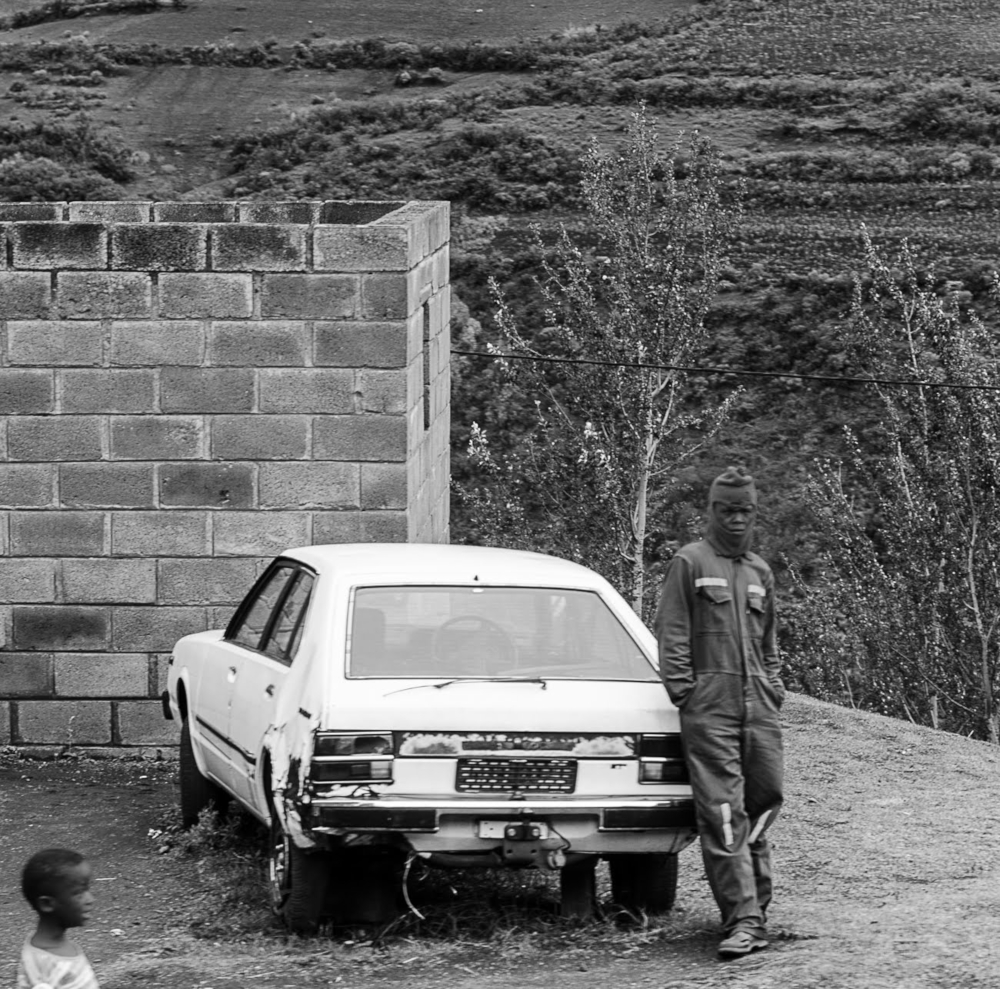

When you get to Kwebulana Junior Secondary School, a school in the small town of Tsomo in the Eastern Cape, nothing sets you apart from the other children. With a few exceptions, all the children in your village, called Zikhovane, go to the same school. They steal each other’s jerseys because they know their parents cannot afford one. But you do not steal. You choose to stay cold until your father buys you a jersey.

Given the tiny steps you take, no longer than a few inches, it takes 40 minutes to get to school and another 40 minutes back. The journey is split into two equal halves, separated by a river. Twenty minutes after leaving home, you dip into the river, home falling out of view, and then from the riverbank, it takes 20 more minutes to get to school.

On the days that it rains nonstop, the fields you walk through to get to school swallow your shoes. The earth is hungry – the soil is soft from years of planting. You stick your hand in, grab the shoe, and drag it out in a twirling movement. Now you have mud for a shoe.

When you leave primary school to attend high school at Tsomo Junior Secondary School, the differences between you and the other children are more starkly outlined. The school tracksuit – the official winter wear – costs more than your parents can afford. And so, in winter you put on a few kilograms when you wear other jerseys underneath the school jersey to stay warm. As soon as the weather becomes warmer you lose this ‘weight’ again without doing any exercise, by simply shedding jerseys.

You start to wonder why you were placed on this earth. Surely, you tell yourself, this is not by God’s design, it must be by someone else’s design. This is the first time that you think about suicide.

3.

While attending a soccer match in the next village, Hange, you run into your uncle. The one who never stops talking – not at a full stop, not at the end of a thought. Your uncle tells you that he cannot read. You know this, everyone does. He tells you why he cannot read and also explains why your father never went to school. He says your father’s education was interrupted by the same thing as his. Your father was 18 when the The Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA) recruiters came for boys his age to take them to the mines as labour. It was deep in the apartheid years then.

All it took to pass the test to work in the mines was the ability to stand up straight, cough up no blood and hold your arms above your head without grimacing. Your father has been working all his life in the mines, yet, he still is not being paid the money he is worth. The life of the black man is such.

It breaks your heart. The consequences of apartheid and cheap migrant labour have travelled, like the gold mines that stretch for many kilometres underground, all the way from the mining town of Sasolburg to meet you right here in this moment.

You think again of that episode at the store, and all the other stores, the tracksuit, the school outings missed. You had started to ask your parents for less and less each day until you stopped asking altogether. If you couldn’t borrow it, you went without, and you were fine with it, or pretended to be.

It was then that you changed your thinking about driving down a highway, air blowing through your thick hair. Now you wanted to get a job so you could send money home. And thus it began. The joy of it … the burden of it. Black tax.

It occurs to you that black tax was always a thing in your family. Your father went to work in the mines at 18 to feed the rest of the family and in a way you were destined to follow the same path, even if slightly different.

Your path will come with the illusion of an education. It is a key to success, they tell you, one that will unlock all doors, imaginary, and otherwise.

By the time matric comes, you have changed your mind about what you want to be so many times that there are not many options left. Each time you look up a new field of study, you realise your parents will not be able to afford it and so your career choice is based on how much your parents can pay, not on what you want to study. Despite their good intentions, it does not help that your teachers keep telling you that you are smart and that one day you will make a highly successful accountant.

You take a gap year after passing matric with a distinction, in the hope that it will give you time to remap your life. You work at a local supermarket to save up some money for university. But after that year, you still don’t know what you want to be and what you want to study.

You enrol for the cheapest course at Walter Sisulu University. There, you share a tiny flat with three other students whose habits you detest. One of them never flushes the toilet properly. The other eats food that is left in the fridge without first checking to whom it belongs.

You work on weekends. You never sleep. You never ask your parents for a cent. You tell them you are fine. You are always fine.

Unlike primary and secondary school, at university it becomes clear that you are not like the other children, but now, luckily, your will is stronger, and so you live within your means, sending money home when you can.

4.

You are now an adult, or trying to be one. On most days, you curse the idea of it, but you are here now and after all, you have wanted it your entire life. As a child, you desired to be an adult and to be exempt from restricting curfews, mapped sleeping and a television schedule.

Here you are then. The adult you have always wanted to be. You move from job to job and in each you negotiate a raise, always at least R3 000 or more. You tell your parents about every job move and spare no details. You tell them how much you are earning now, how many people work at your new company, how many of them are female, black, your age, older – you even tell them the directions to your place of work, although they have never set foot in Johannesburg.

The conversation is carried on the kind of laughter that comes from the belly. Voices rise and drop in a calculated rhythm. It is the kind of laughter that you only share with your parents. Each conversation ends, the laughter still carrying it, and then the list of demands comes. Your mother wants to renovate the old house by the gate. It is not pretty when you enter the yard, she tells you. Nobody uses mats anymore, she says, all the houses need tiles. And there where the small flat is, she wants to build a bigger house, with enough bedrooms to accommodate a small village.

When you are back in the city and looking for a new flat, you enter a lower maximum amount, but you like nothing that comes up. You book a viewing for a flat in a quiet area where there are fewer blocks of flats. The fewer the people, the quieter the block will be, you say. It justifies the price, you convince yourself.

At month end, you send your mother the money for the tiles and the new bedroom. Every month, there is always something else, always costing a little more than the previous month.

In the months that you do not send any money two things happen: your parents call to ask what you think they will be eating; they also tell you that because of your non-contribution that month, they cannot go to a relative’s umgidi to compensate for the gifts they received from them when they sent you to school.

And then the WhatsApps dry up. Your mother stops sending you Bible verses on every day of the week. She stops telling you what trouble your aunt, who is always involved with some married man, has done that week.

You want to know if everything is fine with them, but you are reluctant to ask. So, you wait it out. A few weeks later, you make the call, reluctantly and upset.

This particularly call and the subsequent calls, until you send some money home, begins or ends with ‘Siyalamba apha’, we are hungry here. Sometimes you say how some money will be deposited into your account within the next few days and that you will send her some. On other days, you hang up without saying a word.

As a joke, to temporarily relieve all your aching parts, you post on social media that there is too much month at the end of your money. The message notifications collide as they come in on your phone, interrupting each other’s urgency. All of them are from sympathisers, who are also in the grips of black tax.

You are careful not to post on your WhatsApp story. Once, you spent an entire morning explaining to your mother how it works and since then she has posted so many Bible verses that she could start a whole new religion. You call your parents, moments after baring your heart to the universe, and tell them that the money has been deposited, but that it will only reflect in your bank account after three working days.

That evening, your empty fridge rattles in the background, louder than usual. It does not take long for the two-minute noodles to be ready. You empty three packets into a pot, the meat in the fridge is for lunch.

One weekend, you while away the time at home, sleeping and binge-watching a TV series you have already seen countless times. The opening sequence is the soundtrack of your life. You track the characters with precision and wonder why some had to die and another had to marry the one character you like the least. It reminds you of lovers who refused to watch the series with you or others who did, but fell asleep or dared to get up to answer a phone call.

At the end of another spell of light sleep, you cannot make out if it is afternoon or morning. It only matters in as far as it tracks your own existence, tells you whether you are alive, or not. The light trickles through the curtains to tell you what time it is. It is definitely not evening yet, because the lights are not on yet.

The bedroom you are watching the series from is engulfed in depressing darkness. Only the flashing light of the laptop battles the dark. The rest of the room has succumbed to it. Only the edges of things can be seen. You have no plans for the weekend and no intention to leave the flat.

The next weekend, after sending home all of the money from a consulting job, you are left with just enough to carry you until the end of the month, but then you remember a friend’s birthday is coming up. He created a WhatsApp group for it, on which someone suggests an expensive restaurant in an upmarket area. Everybody nods, thumbs up, as it goes on WhatsApp.

You wait for someone to point out that it is not month end and that the dinner should be moved to a far less expensive place. You’re quite sure at the other end of the group, someone is pacing up and down, also praying that someone will suggest this. The double ticks, the signal that someone is writing, haunt you. At the end, nobody speaks up.

So, the Saturday night arrives, with reservations made at the expensive place. Luckily it is not far from your flat and the Uber won’t cost more than R20 a trip. The meal gives you nightmares – the fucker can easily add up to R500 and so you transfer a little bit of money from your savings. Only for tonight, you say, staring at your judgemental banking app.

The meal is expensive, close to the R500 you had ‘budgeted’ – how laughable. Along with the notification of the transfer comes an urgent SMS from your younger sibling. They need data and money for airtime. Older siblings who have a job cannot not have money and so you transfer whatever was left from what you had set aside for the birthday celebrations. You need to keep up appearances as the older sibling who is everyone’s favourite because love flows unlimitedly through their bank account.

The leftover wine from the dinner calls your name. You drink it to sleep, like others drink sleeping pills. In the morning, your nose draws its smell from the glass you did not finish. One gulp and it is finished, swallowed whole with the flaky dust that floats on top of the wine.

That Sunday is a day to sulk, to remember a job that brings no joy, no money. It is a day to think of black tax and the ways in which its hands extend to your bank account and your soul, wreaking havoc.

You dive into the series you are watching even before opening the curtains and by the afternoon, you remember there is laundry that needs to be done. You drag your body out of bed, you put the laundry in and retreat to bed. To your series. To the soundtrack of your misery.

Another bank notification beeps. At month end, your sibling at university needs to make the required quarterly payments. Somehow, this slipped the minds of your parents when they were busy spending the money you had sent only a few days ago on tiles, pillows and new curtains. Then there are the groceries for your mother and the labour building the new house that need to be paid for.

The thought of all of this, in addition to your rent, car instalment, car insurance, phone, DStv, electricity and petrol put you to sleep. You drift in and out of consciousness.

A friend has given birth to their second child and they send you a photo of the baby wrapped in a blanket with flowers. You send a heart emoji. It is all you can do; your money is already stretched beyond its limits. You realise if you were to have a child now, you would have to feed them with prayers and clothe them in dreams. The thought leaves your mind faster than it entered – it is not wanted here.

Tomorrow it is back to work again, you sink into a state of temporary depression.

The morning arrives and you cry after stepping out of the shower. There is no motivation to leave the flat and go to work. You get dressed whilst shaking from the sobs. The clothes slip onto you reluctantly, your shirt buttons are mixed up and your jersey is caught by something and does not wrap around your neck. You will be late for work, so you tell your clothes to fuck off and you call yourself an idiot.

At last you leave the house, first to face the traffic and then work; to work for a salary that is not enough to last until month end.

Every day of your life you go round and round in circles, because the path of your life has been mapped for you, long before you were born. Your only job is to negotiate the terms of how you follow it.

*LIDUDUMALINGANI is an award-winning writer, photographer and filmmaker. He is the 2016 winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing and a recipient of the Miles Morland Scholarship.

-This chapter is taken from Black Tax: Burden Or Ubuntu, edited by Niq Mhlongo; courtesy of Jonathan Ball Publishers.